From a study of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s life, it appears that he tended to view acts associated with pleasure as tasks, and never indulged (if that is the right word) in a task if it did not conform to his utilitarian or idealistic purposes. Everything from food to sex fell within this grid, and music was no exception. Lakshmi Subramanian’s book, Singing Gandhi’s India: Music and Sonic Nationalism, claims to be the first book to deal with this aspect of Gandhi’s life — his engagement with music.

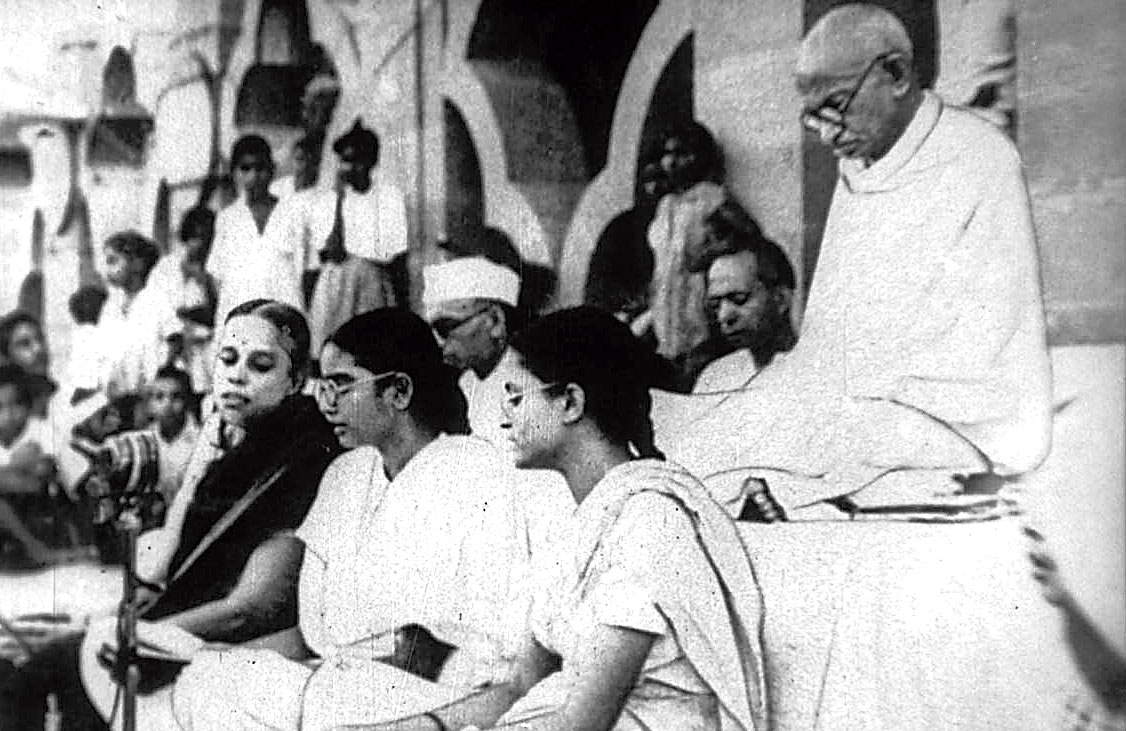

Subramanian’s deep research on Gandhi is, of course, set in an academic layout, but the overall tone of the book is not too pedantic. A pertinent cover design uses a reproduction of a moth-eaten photograph of Gandhi’s face, looming over an ECG graph morphing into harmonium reeds; the text discusses how Gandhi scrutinized and controlled music, attempting to use it to forge his Ramrajya. The preface holds an air of being pleasantly surprised by minor revelations about Gandhi’s relationship with music, setting the tone for much of the book.

The author begins by discussing the late 19th- to early 20th-century music scenario in India, where the need to fashion a discernible, unifying, ‘national’ music was keenly felt by the likes of V.D. Paluskar and V.N. Bhatkhande, albeit for different reasons. This resulted in the evolution and gradual recognition of an umbrella phenomenon, which began to go by the name of Hindustani Classical Music. In this context, Subramanian takes up Gandhi’s relationship with music as a case study. Subramanian gives due importance to the politics of suppression that played a part in both the evolution of the ‘national’ musical identity and Gandhi’s final choice of music. The cant that music as entertainment should be rejected and music for a higher purpose was to be embraced was already in place, professed by both nationalist individuals and societies. Gandhi endorsed and adapted it, so that only bhajan, the North Indian devotional sub-genre, with the possibility of becoming the congregational music of India, was selected as suitable for his purpose. Gandhi had a problematic relationship with classical music. “He did not appreciate the technicalities or... profoundness of the classical traditions in India,” explained Subramanian in an interview. But Gandhi’s sociopolitical acumen led him to use the emerging discourse of classical music and repurposes it to his own ends, to the extent that he insisted on a classically-trained musician to preside over his ashram’s musical activities. The book provides insights into a Gandhi who realized that music had a powerful potential to unite members of the society into a better knit community. So he set about making the practice of his preferred kind of music an exercise for the moral development of an individual, ultimately achieving his goal of communal harmony. The book posits Gandhi as pro-harmony, not pro-Hindutva. However, the author, with her study of the ‘Hinduization’ of Indian music, does inspect the beginnings of the similar, overblown movement today in the Indian sociopolitical environment.

The book introduces some jargon, using the words, ‘music’ and ‘sonic’, that seem to have been used interchangeably in the text. At times, it is difficult to distinguish between the authorial voice and researched matter. Also, the word, ‘public’, has been used repeatedly in the book, to mean the audience, the consumers of music, the dissemination of and access to music, as well as the new musical spaces being carved out by the gramophone, the radio and the diffusion of musical scores via printed books. Yet the contexts have rarely been defined or clarified, and the evolution of the concept of public — that has only recently begun to depend more and more on the ease of dissemination of access — has not been explained. In a book of ‘firsts’, this is a significant overlooking. Phrases like “music entered the public sphere” are likely to be misunderstood unless the context is made clear. Much of the book’s premise relies on the concept of the changing public and publicization of music for a given value of ‘public’. Readers should not close this book with an unclear understanding of this concept, nor is it their responsibility to research the context of their reading.

Singing Gandhi’s India: Music and Sonic Nationalism by Lakshmi Subramanian; Roli, Rs 495