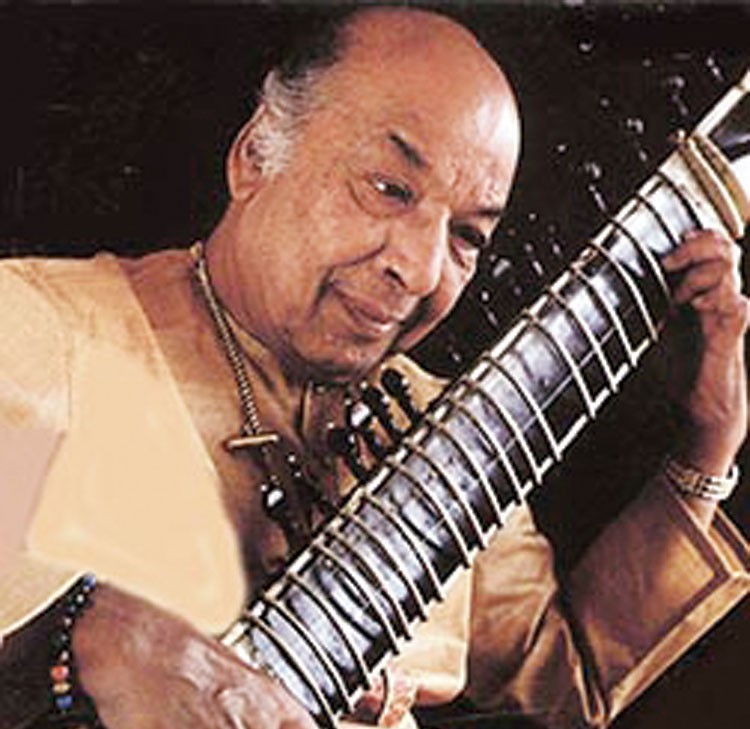

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan by Namita Devidayal does not overtly attempt to prove Khansahib Vilayat Khan’s greatness above all other musicians. A great mercy because artists’ biographies in India tend to be hagiographic, therefore, flat. Devidayal’s portrayal is more 3D, although her depiction of a multifaceted human being possibly affects the portrayal of the artist. The jacket has a traditional design, featuring the dapper ustad, probably singing amidst a sitar recital.

In The Music Room, Devidayal saw herself coming to terms with the weight and the snarls of tradition that define Hindustani classical music. In The Sixth String, she depicts a genius, gharanedar musician treading this terrain. By presenting Khan as exhibitionist but conservative, egotistic yet charming, nothing is excused or indulged as idiosyncrasy of an artistic temperament. Devidayal, a non-performing vocalist of the Jaipur-Atrauli gharana and not an Imdadkhani instrumentalist, is as unbiased as she can be, even though she does not much explore what Partho Datta has called “Vilayat Khan’s life-long tussle with the Indian establishment” in post-Independence India where “the public sphere increasingly came to be dominated by smug Brahminical nationalists”, leading to the maestro’s sense of exclusion.

Anecdotes abound in the text, which is brought to life through conversations. The reader is carefully familiarised with the golden age of All India Radio and the ambivalent relationship it had at first with classical musicians. This is significant, as technological developments in the history of music in India are often glossed over, as if music has only been disseminated from guru to shishya, heart-to-heart. Khan’s life serves as a point of insight into the era. A little more on the transition of patronage from the princely states to AIR might have been better. Devidayal perceptively shows the assimilation of the different schools and influences of music into Khan’s own. Suitably acknowledging the roles played by D.T. Joshi, Bande Hasan, Amir Khan and yes, even Ravi Shankar, is quite a feat. She also recognises those who stand behind the greats, perhaps equally great themselves. Basheeran Begum, Imrat Khan and Z.A. Bokhari’s presences stay with the reader as the story ends.

For a story it is, as Devidayal says. Her telling is stark, but her prose fluid, her style amorphous, her genre overlapping. It is not her intention to provide an insight into the artist’s creative process. In trying to “make classical music cool again” for the current self-loathing generation of Indians, Devidayal seems to want to bust the myth that all Hindustani classical musicians are dour and tedious, hence the reversal of the idiom of enquiry. But does ‘storytelling' mean that Amir Khusrau can be relocated to Persia? Besides being a biographical account as maverick as its protagonist, the book is also a documentation, albeit anecdotal, of the tangled heritage of music. Is not leaning towards the subject a stance taken by all biographers unwilling to displease the living relatives of a late artist?

To say that the musician who draws tears out of every listener is greater than one who almost single-handedly generated an international interest, is too simplistic. Yet, in her search for sensationalism in the relationship between Vilayat Khan and Ravi Shankar, Devidayal manages to voice the assumptive confusion inherent in listeners, of comparative and competitive greatness of musicians. Perhaps more empathy was needed. Portraying the artist as a complex human being is a writing tradition mostly unrecognised in India. It makes an enticing read for laypeople, but this book may not please practising musicians, especially scions of the gharana. Dismissal is a fate worse than stoning.

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan by Namita Devidayal; Rs 690; Context