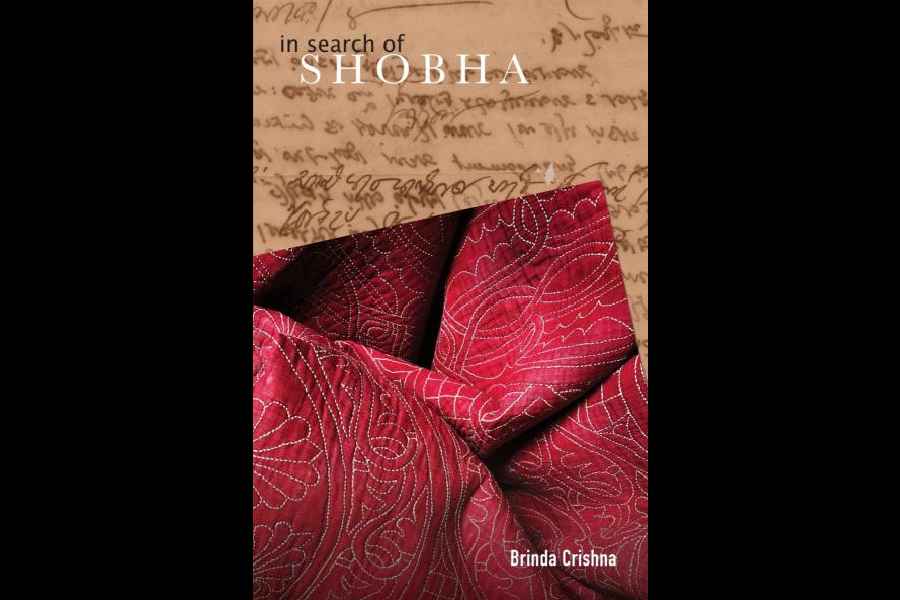

Author Brinda Crishna has just published In Search of Shobha, a finely-crafted family memoir that would resonate with many young women who are now seeking their roots in the stories of their grandmothers and great-grandmothers who were untiring in their fight for independent identity even as India was battling for her Independence over a century and a quarter ago.

The story is fascinating and anchored in letters, poems and documents that dig up the beguiling family history of Shobha Bose, the author’s paternal grandmother and a woman ahead of her time, who was born at the cusp of two tumultuous centuries. The letters were written to her by a man who loved her before she was married but was not her husband. The letter came into Brinda Crishna’s possession after the passing of her father.

Shobha graduated from Bethune College, Calcutta, in 1915, one of the few women in Bengal to get a college degree at the time. She went on to become the principal of one of the first non-missionary schools for girls in Kanpur, opting to work independently all her life after her husband lost his money in an ill-fated business venture in Giridih, Jharkhand, leaving her to bring up her two children with no financial support from him.

Q You say the seeds of this intriguing book, In Search of Shobha, lay in the innocuous package of letters from your grandmother Shobha that emerged among your father’s papers. Can you tell us how it blossomed into a project?

I had been visiting my mother in Pune. I was nursing her after a cataract operation. We had finished breakfast and I was waiting for my sister to pick me up to go to the airport. My mother handed me a small plastic bag with letters in it and told me, “I found these in Baba’s box. I think they are letters from his mother to him. No use to me, but I’m sure you could do something with them. They are in Bengali and someone will be able to translate them for you.”

I definitely felt some curiosity, as we knew nothing about my father’s side of the family and this was a rare moment when his mother was actually being mentioned. I put them into my bag, carried them home to Calcutta. put them on my desk, and actually forgot about them for a while as my everyday life of work and running a home took over. Every time I sat at my desk I would look at them and think, “I really must do something about these”.

I did open the packet a couple of months later, on Baba’s birthday, and the first thing that caught my eye was a copy of a graduation certificate for a Shobha Mukherjee. I remember being filled with a sense of curiosity and began to look through the rest of the package and found many letters, some addressed to Shobha Mukherjee, and some to Shobha Bose written in Bengali in a beautiful script. I was fascinated and totally excited.

I immediately called my friend Indrani Roy, who is fluent in Bangla and English and asked her to come over and read out these letters to me since I could not read or write Bangla. She came over a couple of days later and we opened the package together. When we discovered that these were not letters from my father to his mother as I had thought, but were letters written to her by someone who had loved her when she was a young girl, I realised I needed to find out all that I could about this elusive Shobha Mukherjee who became my grandmother Shobha Bose.

Q One is almost immediately struck by the compulsion you felt to read the stories, letters and poems since you are a probashi Bangali and do not read or understand Bengali. Was that one of the most daunting tasks about writing the book?

Possibly the most daunting task was to find someone who could actually read them and possibly transliterate or, more importantly, translate them in an honest and truthful manner, authentically keeping to the language. Indrani couldn’t do them as she couldn’t quite get the script, written in a very stylised manner and the language which was old Bangla.

Q Although many would argue that something is lost in translation, something is always gained, as Salman Rushdie puts it. Would you like to say how you feel about translation?

I don’t think I had any issues about the translation as the person who finally did them was amazing. She not only understood and could read the letters, she also had an understanding of the time. So, the letters came alive for me. We developed a deep friendship and I completely trusted her.

Towards the latter half of the book, when I was checking facts, she sent some of the poems to Indrani, who translated them independently, just to make sure we had got it totally right. Also, my first translator had such an incredible command of the complexities of the Bangla language that there was no doubt that she was totally accurate.

Q Your driving factor in the 10 years of being focused on this project was, as you say, finding your roots through your grandmother’s stories and poems. And, in the process, you say you understood your rich, chutnified self. Were you surprised by what you discovered about yourself in the process?

I don’t think I was surprised. I had lived in Bengal for many years, so understood the culture, the space, the food, and was drawn to it naturally. What surprised me was how ‘Bengali’ I actually was, in spite of having grown up all over India.

Q What kind of a person was revealed through your grandmother’s writings? What are the anecdotes that you wanted to hear more about?

As I slowly got to know her, I realised she was an outstanding human being — honest, filled with a deep sense of duty to her family and to what she had committed to do. She was unlike regular girls of the time as she was serious and believed strongly in education for girls. She was a deeply spiritual person and took her Brahmo faith very seriously and tried to live by the tenets of her faith. Yes, I certainly met people from my father’s family who I didn’t even know existed, especially his first cousin, who has become a great friend of the family.

Q Your daughters were great supporters of this project. How did the making of this book affect your bonding together? What has this book done to bring you closer?

My daughters have always grappled with the fact that they were not typically from any one community.

The writing of the book and the sharing of bits and pieces of it, of facts suddenly appearing as I went along, gave them insights into themselves and their roots. We are a very close family anyway and I think this book just cemented that.

Q. How do you now understand and value your extraordinary inheritance of being a Brahmo, especially an inheritor of the Romesh Chandra Dutt and Toru Dutt lineage? And now how do you identify yourself as a Brahmo?

I am a practising Christian. But understanding the Brahmo faith gave me a better understanding of my father, where he came from and what made him such a wonderfully honourable, truthful and honest human being.

Q. You have served disadvantaged human beings and had the most empowering education in India and overseas. Could you speak about the importance of education for the betterment of women and others on the margins and how society at large understands women’s and marginalised issues when the larger populace is educated?

Women form the backbone of a society. I do believe that. They play multiple, and often balancing, roles throughout their lives. Education and knowledge add confidence, value and pride to human beings, and more so for women who have been marginalised for centuries and continue to be. Since I believe in equal rights and opportunities for all people, I have fought for the most marginalised of them, for children and families of children who are differently abled.

Q. What about the roles of friends and others at Brahmo Samaj, Calcutta?

The translator was the person who brought Shobha and her times alive for me. Indrani heard me out as I tried to grapple with thoughts and ideas and make sense of moments in the book. The people in the Brahmo Samaj were amazingly forthcoming and helpful, generous with time, and allowing me free rein in the incredibly beautiful library.

Q. What are your memories of school in Darjeeling, being a spouse of a highly respected tea industry man, and what do you love and hate about Calcutta?

I was sent to Loreto Darjeeling as it was my mother’s old school. Did I love school? No, I did not, as I found it very conservative and strict. However, I did develop my love for reading in school, as we had a very well-stocked library. And I loved the beauty of Darjeeling and being in the mountains.

Being Viveck’s wife and the mother to my four girls is what has defined my life. Viveck is my other half. He balances me in a way no one else could ever do. He is my closest friend. The book would not have been possible without his support. We have different interests, but that has only brought us closer.

Q. Who do you think this book will appeal to in Bengal and overseas and why?

The book captures a snapshot of a time of great social change in Bengal, particularly for women, to which today’s generation owes a great debt. I think it will appeal to the Bengali diaspora worldwide. It is a human interest story capturing remarkable open-mindedness 150 years ago, and thus should have broad appeal to anyone who is interested in stories of the past, of discovering roots.

THE LOVE THAT COULD NOT SPEAK

In the quest to find the answer to ‘Who am I?’, the eternal question which writers from Shakespeare to T.S. Eliot were flummoxed by, the feisty writer Brinda Crishna began her journey by opening a cache of 70 letters that were among her father Lt. Col. Nikhilesh Bose’s papers.

It is a colossal task the author sets for herself from the time she and her close friends Indrani Roy and BM (known only by her initials for anonymity) began first to deconstruct the letters, and then reconstruct her grandmother, Shobha, a woman who seemed larger than life and a century ahead of her time.

To that fiery amalgam add the passion and intensity and love and devotion to a highly intelligent man with an unique name, Utsavananda, who loved and respected Shobha immensely but was someone she could not marry.

A few of the 70 letters were damaged or indecipherable, and some were so intimate that they could not be shared. Among them are love poems written by Shobha and Utsavananda.

For a young, highly sensitive scholar who has just entered college, to be courted by a man who is ten years older and more worldly wise, is very tempting. And this is where Crishna becomes a strategic storyteller and her translators, and editor Anjum Katyal, are excellent pillars to her literary project.

Utsavananda writes to young Shobha in terms which elevate her to the position of the divine feminine — a goddess. It is a somewhat ambiguous analogy for a Brahmo to use the language of veneration that was the stuff of Hindu traditionalism for Utsavananda to describe Shobha, though some might find close echoes with Bimala and Sandip in Tagore’s Home and the World.

Utsavananda writes in one letter: “I see you as the personification of Shakti and I pray that you remain so, and in your strength absorb all my weaknesses and so we shall start our lives together in the eyes of God. And if that does not happen, if our lives are filled with desires and greed then we will both perish. Should we not try to save ourselves from this death? Should we not try to make our love immortal? Will you not stand beside me as my Devi, as my Shakti? I want you, I want nothing but to make our lives immortal. I am there where you are, I am not there where you are not, I desire that our lives are forever, immortal, faithful.”

All great literature comes from great pain, say writers through the ages, and it’s the same with Shobha and her lost love, Utsavananda. They were made for each other but Shobha found she had suddenly evolved into a truly independent person with a mind of her own and no longer wanted to marry Utsavananda. It was as if she had outgrown her need for him.

Crishna writes: “Nevertheless, a deep sense of loss engulfed her as she acknowledged that Utsavananda, who had opened her mind to the world, could never be her life companion. And yet he would always be part of her life. From the letters we know that he stayed in touch well after her marriage and motherhood, not just as an occasional contact, but as someone who was up to date with intimate details of her daily life.”

Surprisingly, Shobha marries a gentleman suitor, Sibesh Bose, against her father’s wishes. Sibesh looks fine and dandy, but is an irredeemable gambler and inconsistent in his businesses. So, Shobha has to go out and work to support herself and her children.

The author has done meticulous research with innumerable relatives and friends, polyphonic voices incorporated into the tellings, from family members Meena pishi and Arti Sen, and Mrs Mazumdar in Delhi, who was once principal Shobha Bose’s student, spanning geographical boundaries that often smudged their borders from Cornwallis Street to Giridih and from Santiniketan and Calcutta, like the love and longing that seeped through the definitively dark handwritten letters.

Crishna’s taking of notes and spending long hours at the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj library, a journey in which she included her daughters, was a unique way to incorporate generations of women in the “telling” of this family saga — not unlike the way some Victorian women writers who deployed a descriptive style as well as representation of male characters as well as a certain mystery element in their narratives (think Jane Austen or the Bronte sisters).

Why Utsavananda desired Shobha as his upasana, or muse, and how this relationship became an incentive for her to be more exposed to new ideas and the world is intriguing. After all, the freedom for women to move unfettered without purdah, to get an education and stand on their own two feet was what Brahmos were fighting for and the story of Shobha’s personal goals is linked to the creation of the New Age women from 130 years ago.

It is to Crishna’s credit that she is attentive and acutely sensitive to the way the richly crafted poetry of Shobha Bose shows an interesting evolution in her self development. As the years go by, Shobha’s vivacious, free-spirited sense of joy unbound is replaced by a lack of spontaneity. She is sombre and brooding and burdened.

Crishna says. “The poems I found in her notebook strengthen the picture of this earnest girl child, who grew into a serious young woman. It is obvious from the changes in mood and style that they had been written over an extended period of time.”

Here is a sample of one of Shobha’s poems:

Those who are unkind are devoid of humanity.

Kindness is the great religion, kindness is the ornament.

The Almighty has created this invaluable gem.

Without kindness, man becomes a beast

And can no longer have a place in Society.

Why should we become beasts in human form?

The power of the value of kindness is overwhelming. It is as if kindness becomes the sole mantra — something like what every scholar who learnt under the watchful eye of a missionary recited to himself as he got ready for class after the Assembly: “If you can be one thing, be kind.”

There are so many ways to read Shobha Bose’s poetry, which Crishna has made visible and eminently accessible to us. One very tempting way to read this poem is to locate it in the famines that plagued the heartland of Bengal — its cities and rural landscapes. A Marxist reading demands the recognition of how egregious human beings are when they are driven by greed and the need to possess material wealth at the cost of human life.

Over time, the poems turn almost cathartic, a way of release for an extremely private person. She writes in a poem called Lord:

Lord! Forever light Your lamp

So that I may see beyond life, death and darkness.

The contribution that Crishna’s family memoir makes to the larger arena of social history of Bengal lies at the intersection of personal history with the national movement for emancipation of women before and during Indian independence. Perhaps more than any other factor, the book must be applauded for its epilogue which is revealing in the scintillating conversation between Crishna and BM about why Shobha took the road less attractive by marrying a man with whom she had no common interest rather than a man who loved her to distraction.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Master’s English at Loreto College