Book: Empire Of The Scalpel: The History Of Surgery

Author: Ira Rutkow

Publisher: Scribner

Price: $29.99

Ira Rutkow’s riveting book can be read simultaneously as a developmental history of surgery, both in terms of an incremental accretion of techniques and technology and changes in the profession and in professionalisation, as well as a reflection on how his own experiences as a surgeon fit within the history of surgery. Rutkow argues that four features are fundamental for a contention with the history of surgery: “1) an understanding of human anatomy; 2) the ability to control bleeding; 3) minimizing the risk of infection; and 4) reducing pain.” The bulk of Empire shows how these developments occurred via trial and error and the occasional flash of far-reaching insight but were also bogged down by existing orthodoxies, institutional pressures, and egoistic clashes between personalities.

An engaging aspect of Empire is how Rutkow slips in vignettes of his own surgical experiences in his recounting of the history of surgery. Here is an important passage that occurs when Rutkow was a greenhorn: “The professor asked if I understood the historical significance of what I had just seen. I was uncertain what he meant. Obviously, a life had been saved and I’d gained invaluable clinical experience. But I remained puzzled by the question. He told me that he was a student of surgical history and thought it important for surgeons to understand their profession’s past. The Harvard don then explained that a trephination was the earliest operation known to mankind and how, thousands of years ago, cavemen chiseled holes into the skulls of other cavemen for spiritual reasons, probably to release evil forces… As the professor left, he turned to me. ‘Keep in mind,’ he said, ‘your experiences are tied to the experiences of all the surgeons that have gone before’.”

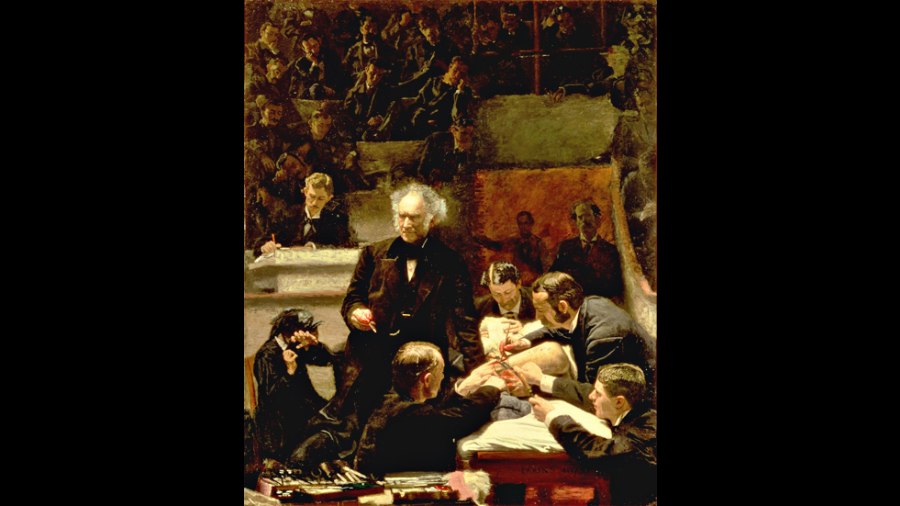

This pivotal moment becomes a guide to Rutkow’s career, both as a surgeon and a historian, as he follows the tracks left by surgeons “that have gone before”. Empire examines the development and growth of the practice and the profession by focusing on personalities. A recurring narrative technique is exposed as Rutkow follows the tracks of those who came before him. While he focuses on what the historical personality contributed to surgery, he also provides brief character sketches that add an interesting flow to the narrative. Thus, the name of the Roman, Galen, was “derived from the Greek adjective galernos, meaning ‘calm’; he was anything but… (he was) self-absorbed and self-righteous, while his writings reveal his contentious behavior.” Joseph Lister, who extended Louis Pasteur’s germ theory and perfected the revolutionary technique of antisepsis, may have been cold and distant in his social relations but was “a guileless, humble, and level-headed individual who showed unfailing sympathy for the afflicted”. Charles Drew, an African-American surgeon, a major figure in the history of banked blood and the struggle for racial equity in the profession, was “Broadshouldered, handsome, and tall… carried himself with an obvious air of authority”.

Empire is a panoramic, engaging and well-researched history of surgery. But it may have been strengthened by reflecting on a statement that Rutkow makes at the beginning. Stating clearly that he is writing a history of “Western” medicine, Rutkow says the following about the “East”: “‘Eastern’ Medicine, exemplified by Indian practices, enjoyed numerous surgical achievements, especially plastic and reconstructive procedures, including development of a renowned method to reconstruct the noses of individuals who suffered a traumatic injury. However, these successes did not markedly sway the overall organizational, scientific, and technologic developments of Western surgery that became the global norm.”

It would be useful to reflect here on why such successes from other parts of the world (not India alone) did not become part of the “global norm”. This would have probably led to a narrative of the practice that is more global and inclusive.