It is a tale of two cities, and of two women. But more than that, it is a tale of loneliness that is all pervasive. A novella made up of six parts — each of which can be read as an individual story — Not Quite a Disaster After All offers glimpses into the lives of two women who live under very different circumstances. Anjali and Anita — both first-person narrators — are like foils of each other on the surface. Anjali is not only born into an aristocratic family in Calcutta and well-provided for by her parents, but she is also a successful author in her own right. After an unfulfilling relationship, she has settled into the comfort of being a single woman who has to answer to none but herself. Anita, on the other hand, has to count each penny and measure out her indulgences. She is married to a pretentious man who aspires to be a writer and has only condescension for his wife. But Anita cannot shrug off this familiar hell to make a bid for independence; so she seeks solace in imaginary situations where she has a partner who desires her.

They may seem like chalk and cheese, yet, at their core, both characters are moved by the same things: discontent and loneliness. Neither woman fits in, no matter how hard she tries. One gives up trying and the other never stops and both are unhappy because of it. But their lives are ‘not quite a disaster after all’, and they constantly accommodate this status quo.

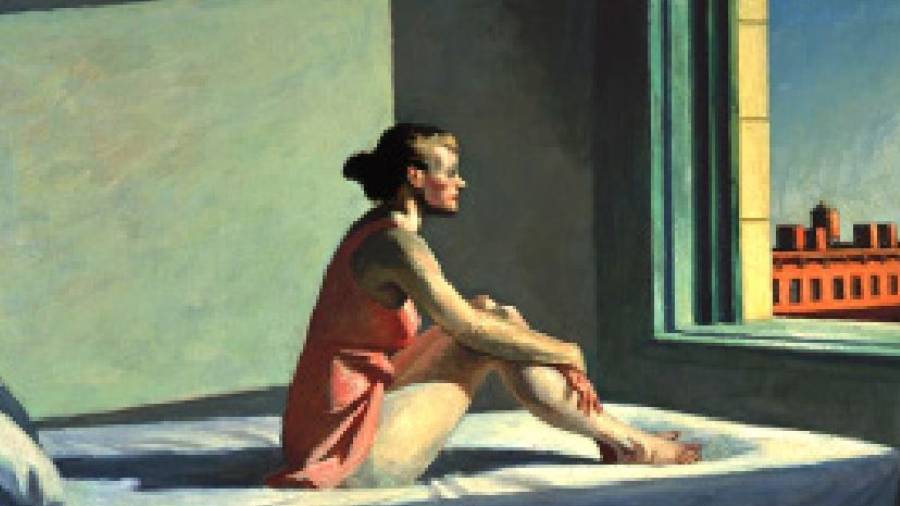

While their partners do appear in the plot and other characters flit in and out, we always find the two women alone, sometimes in scenes reminiscent of Hopper’s paintings. Buku Sarkar is also an accomplished photographer: her writing, unsurprisingly, is marked by a strong visual element. This is especially true of her descriptions of Calcutta and New York; while one remains stuck in a musty past, change is the only constant in the other. Yet, both breed alienation among its citizens.

All the stories are informed by binaries — affluence and privation, loneliness and companionship — and the characters reside in the shadowy zones between these extremes. Anjali is always conscious of her familial wealth and knows that it is one of the reasons she cannot fit in. But she never turns away from privilege, ridding her character of a conscientiousness that is ornamental. This touch of realism may make it difficult to like Anjali. Yet, she shines in her unabashed disinclination to please others. In prose that is as shorn of embellishment, much like the photograph on the book jacket, Sarkar offers vignettes that whet the appetite to savour more detailed sketches of the lives of these two women.