In the City a Mirror Wandering By Upendranath Ashk, Penguin, Rs 599

A young(ish) man, struggling to realize his dream of becoming a writer, sets out of his house early one morning and wanders through his hometown, Jalandhar, over the course of a single day. He is supposed to return to Lahore soon, where he works in a newspaper office that affords him little time to focus on his literary ambitions. Chetan, the authorial alter-ego in Upendranath Ashk’s seven-part series of novels, Girti Diwarein, is the quintessential Modernist male protagonist. He is aware of his privileged position in a Brahminical, patriarchal society, feels stifled at home among his family, but usually withholds from acting upon his sense of justice for fear of disturbing the universe.

In the City a Mirror Wandering (Shahar Mein Ghoomta Aina), the second volume in the series, came out in 1963. According to his biographer and translator, Daisy Rockwell, Ashk had antagonized several important members of the Hindi literary milieu in Allahabad by this time. He had had a fallout with Mahadevi Varma, who had allowed him refuge at the Sahityakar Sansad Bhavan. He had ridiculed his critics in the second edition (1951) of the first volume, Girti Diwarein, for failing to meet his work on its own terms and had refused to comply wholly with any of the contemporary literary/linguistic movements (the Progressive Writers’ Association; Dayanand Saraswati and Gandhi’s attempts at standardizing a lingua franca) that were shaping the Hindi canon.

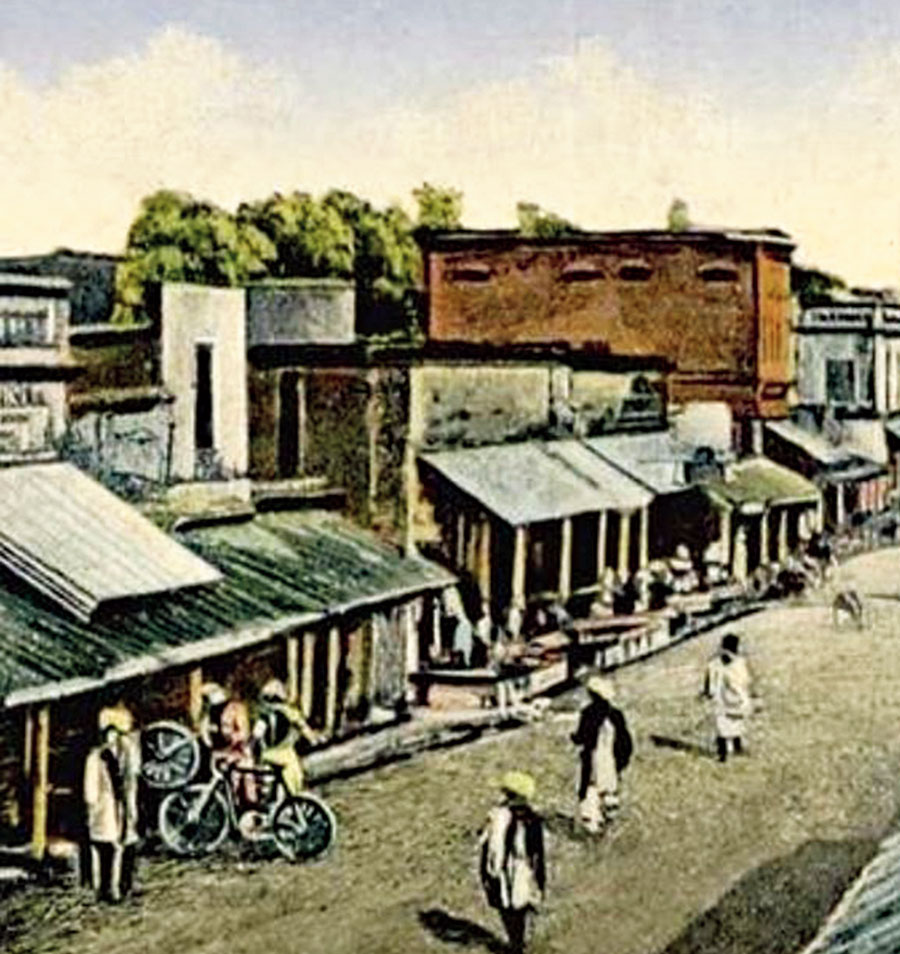

Like its prequel, In the City ostensibly lacks a plot. Chetan rambles through the chowks and bazaars of Jalandhar of the mid-1930s, meeting all-too-familiar faces that appear like ghosts of a different lifetime. This socio-geography would be new to an English readership but nowhere in Rockwell’s translation does it appear exoticized or even remarkable. The speech of everyday life comes across as less stylized and patronizing than many Indian English novels from the period, which took up the project of forging a new linguistic register to represent the masses. And for all that, the novel does not lack localness.

Ashk’s use of free, indirect discourse allows him to switch between the perspective of the aspiring writer and layered memories from his growing years. All through, Chetan takes a keen interest in watching manufacturing processes: be it the soda bottles at the Mandi Soda Water Factory, the papad-makers of Papadiyan Bazaar, or the lock-and-keysmith’s workshop. In a city where Chetan does not find originality in art and literature, these digressions function as ekphrasis. They are rich in sensory detail and draw the reader in to pause and revel in the minutiae of everyday life.

In spite of the constant meanderings of the narrator, however, there is a profound sense of stagnation in the society he portrays. The people he had left behind in search of a lettered livelihood seem to function within an unhurried and insular microcosm. In the countless chowks, shopkeepers and customers continue to rehearse their skills at baits, cards and chaupar, as faux poets hold sycophantic followers in thrall with borrowed verses. One of these poets, Hunar Sahib, attempts to extort petty cash from various patrons — political and religious — cleverly substituting in his inspirational poetry the word ‘Nation’ with ‘Ram’, depending on his audience.

The novel holds the reader in constant tension, blurring boundaries between fact and fiction, author and protagonist. Perhaps, this is part of the reason why critics attacked the novel when, in fact, they had quarrels with its author. Ashk begins with a subtle misquotation of Stendhal, where he claims to be the mirror that represents life as it is. Its seemingly dispassionate stance towards ‘reality’ offers no sense of moral, aesthetic or social justice. Instead, it solicits an acceptance of the grime and messiness of life.

Inevitably, the novel has drawn comparison with European predecessors, in particular with Proust, Woolf and Joyce. Rockwell refers to a review which at the time had described In the City as “Ulysses in Jalandhar”. In Ashk’s biography Rockwell seems to underplay his familiarity with the Modernists slightly, referring primarily to his use of Rolland’s Jean-Christophe and a casual exchange about Proust. In the Introduction to Falling Walls, however, Ashk lists among possible influences Turgenev, Galsworthy, Sholokhov and Premchand, apart from Rolland and Woolf. He confesses that his search for a “pattern” came to an end with a novel by “Virginia Woolf or some other writer from her group”, which “was limited to the hero getting out of bed, going to the window, and taking a walk”.

The English translation will allow Ashk’s novel to enter circulation within a different critical framework, where considerations beyond the prescriptive social realism of his time or canonical demands will re-evaluate his work. This runs the risk, of course, of overvaluing a Euro-centric understanding of Modernism and the purpose of literature, but it is a risk worth taking, because the novels themselves are absolutely riveting.