The first week of February is dedicated to writers and illustrators of children’s literature — gifted artists who shape young minds in the latter’s most formative years. There are many challenges to crafting a book for children — the most discerning and unforgiving of readers. Every choice one makes — of characters, skin colour, gender — may well leave a lasting impression.

The challenges notwithstanding, creating children’s literature can be a refuge for writers and illustrators. When Stalin’s Great Purges made writing dangerous in post-revolutionary Russia, a group of avant-garde artists turned their attention to children’s books — a relatively unsupervised sphere at first. Collaboration between experimental authors like Alexander Vvedensky and Daniil Kharms and visual artists such as Vladimir Tatlin and El Lissitzky made Russia in the 1920s and 1930s a surprisingly verdant turf for illustrated children’s books.

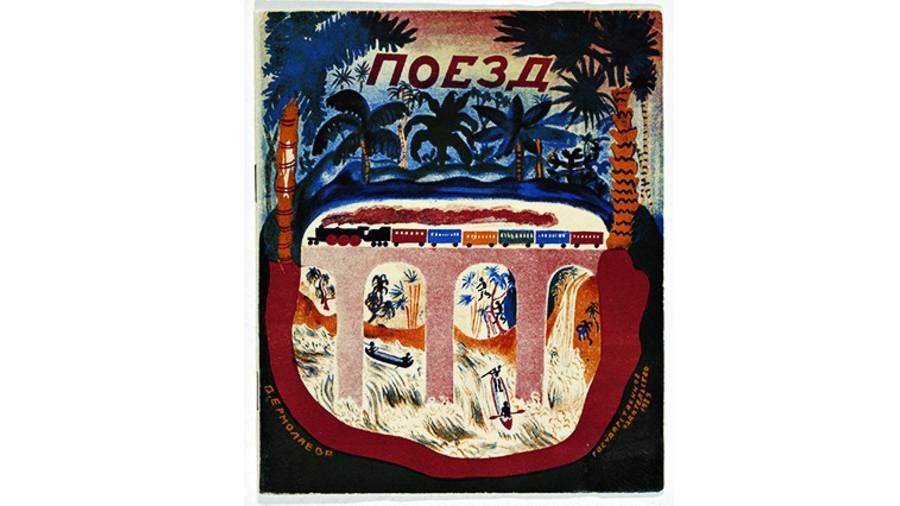

A century ago, in the decade following the Russian Revolution, the Children’s Department of the State Publishing House was conceived of and set up in Leningrad by artists like V. Lebedev and V. Ermolaeva — these names would be familiar to Bengalis who grew up devouring translations of Russian children’s books. They changed the way of viewing and imagining literary art for the young. Instead of simplifying art for the sake of children, these artists experimented with styles like Suprematism, Futurism and Cubism, combining these with folk art traditions that would have been familiar to Russian children cutting across class and gender. Take, for instance, The Circus, which fused Suprematism with the Lubok folk art tradition. Lebedev designed the book as a cascade of tricks: every page illustrated a different trick. The simplicity of the toy-like figures in primary colours is balanced by the clever use of textures to differentiate among clothes, wood and skin. Another masterpiece is The Train (picture). Illustrated by Ermolaeva, The Train is a story about eight boys who travel across the world — full-page illustrations give the sensation of vast spaces that change with the flip of a page. To depict the diverse settings that the locomotive passed through, the tiny carriages were made to move exactly across the middle of each page, with contrasting colours — browns and reds of the desert and the deep blue and purple of the sea — blooming on either side of the sheet.

Even as art blossomed, clouds were gathering on the horizon. The official party policy, stated in Nikolai Bukharin’s The ABC of Communism (1920), was “[t]he salvation of the young mind and the freeing of it from the noxious reactionary beliefs of their parents...” A poster on childcare warned, “Do not tell stories to a child before he goes to sleep, or you will disturb him with new impressions... Never tell a child about things he cannot see (this means that fairy stories should not be told to children).” Unsurprisingly, many of these authors and illustrators were forced to change their careers or lost their lives in the Purges.

The next generation of Russian illustrators flowered only in the 1960s. One thing this new crop of artists had in common with their illustrious predecessors was that they had grown up poring over the works of Lebedev, Ermolaeva, N. Lapshin and so on. So while Stalin may have been able to plunge Russian children’s literature into darkness for a while, he could not uproot the seeds of imagination sown by a group of visionary artists.