Book: A CONSTITUTION TO KEEP

Author: Rohan J. Alva

Published by: HarperCollins

Price: ₹699

Under the World Press Freedom Index 2023, India was ranked 161st out of 180 countries. India’s rank has steadily slipped from 133rd back in 2016. The press is the canary in a country’s free speech coalmine. If there is a time to be concerned about what you are free to speak of, it is now.

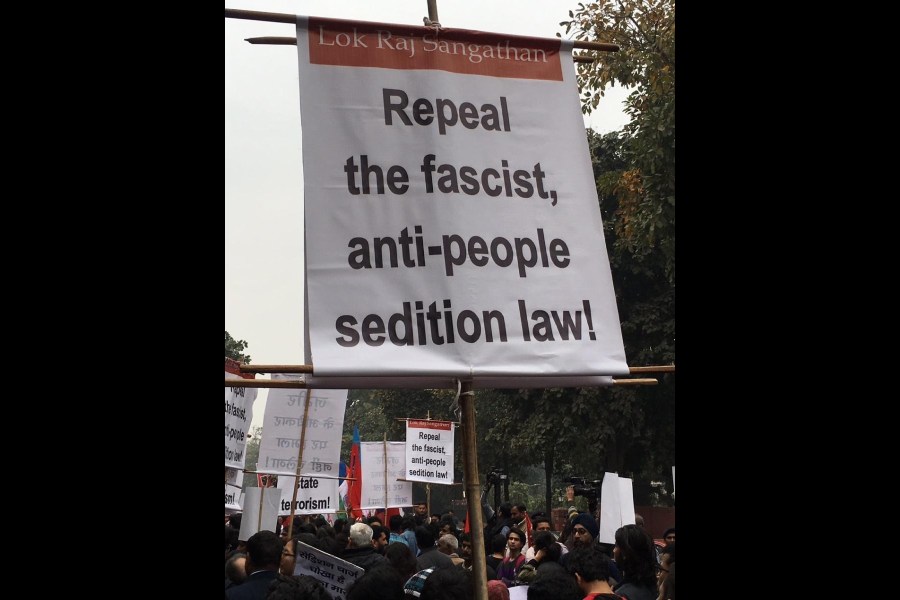

Part of addressing this concern involves recognising the structural conditions that create space for speech. Many issues await solutions here: concentration in media ownership, the physical security of reporters, the treatment of the political Opposition, digital surveillance and censorship, and the space for dissent and protest. In many of these matters, legal rules play a leading role, such as in the impact of criminal defamation and anti-terror laws on dissent. However, whether in terms of vintage or in terms of symbolic disregard for freedom, there is one law that continues to reign in the totalitarian statute book: sedition.

Rohan J. Alva’s A Constitution to Keep diagnoses this old affliction. Inflicted upon us by the British, disavowed by our Constitution’s framers and, yet, resurrected from its grave and forced to carry on in the fashion of the undead, sedition’s story is tired, tragic but always telling. As a legal rule that punishes persons who encourage others to harbour “disaffection” or hatred against the government, it has consistently been cautioned against since the time of the raj, sometimes even by Britishers. Freedom fighters have survived its maws, judges have hacked at its limbs but it marches on. After the rule was suspended by the Supreme Court last year, a recent Law Commission report has called for an (inadequate) amendment to the law, supposedly to blunt its edge.

Alva’s project is a commendable one: he seeks to show that sedition, no matter how we conceive of or interpret it, cannot have our Constitution’s blessings. He marshals historical material on the drafting of the Indian Penal Code, court proceedings and judgments during colonial times, decisions made by the Constituent Assembly, and modern jurisprudence on how the right to free speech should be worked. He tries to show, for instance, that contrary to the views of some, the 1951 First Amendment to the Constitution did not, in fact, revive sedition and that it has been dead since 1950. Alongside this negative project of showing how sedition cannot be saved, Alva also makes a novel case (in the Indian context) for differentiating types of speech and providing strong protections for political speech directed against the government. This is a worthy proposal that may address many of our present concerns.

The writing delves into subjects such as the conduct of colonial judges, the propriety of judicial reworkingof legislative text, the relationshipbetween “public order” and “security of the State”, and decades-old American jurisprudential debates on the likelihood of violence or harm caused by speech. Due to the language involved, lay readers may find some of these parts difficult to navigate. Readers with some legal knowledge, on the other hand, may benefit from studying the book’s central proposal.