At the very outset, a disclosure: the author and I were colleagues about 25 years back. So I can say with confidence that he belongs to that small group of journalists who know a lot about the Sangh Parivar and are completely objective in their assessments of it. And that’s what makes this book different.

This book is not about the RSS. It is about the men -- and one woman -- who created the RSS and sustained it since its formation in 1925. In the order of appearance, they are K. B. Hegdewar, V. D. Savarkar, M. S. Golwalker, S. P. Mukherjee, D. Upadhyaya, B. Deoras, Mrs V. R. Scindia, A. B. Vajpayee, L. K. Advani, Ashok Singhal and Bal Thackeray. The last two are a surprise, as is Mrs Scindia who was more BJP than RSS.

Also, it is written with complete detachment and without the slightest trace of admiration or detestation for the subjects of the book. This book is a must read for anyone trying to understand Narendra Modi’s mind.

Mukhopadhyay has also taken care not to clutter the chapters up with an excess of detail in the way academics are prone to. He sticks to the bare but relevant facts about these people and what their endeavours were. The only thing that mattered to these people was Hindu resurgence.

All of them had different approaches to a common conviction: that Hindu society needed to unite for a variety of purposes. These ranged from opposing the British to dismantling the caste system; to provide education and livelihoods to defending India. And so on.

As you read the book, it quickly becomes apparent that while the RSS, as an organisation, is a top-down one, in its internal thinking it was completely democratic. There was no central party line for each and everything as there tends to be in other cadre-based organisations.

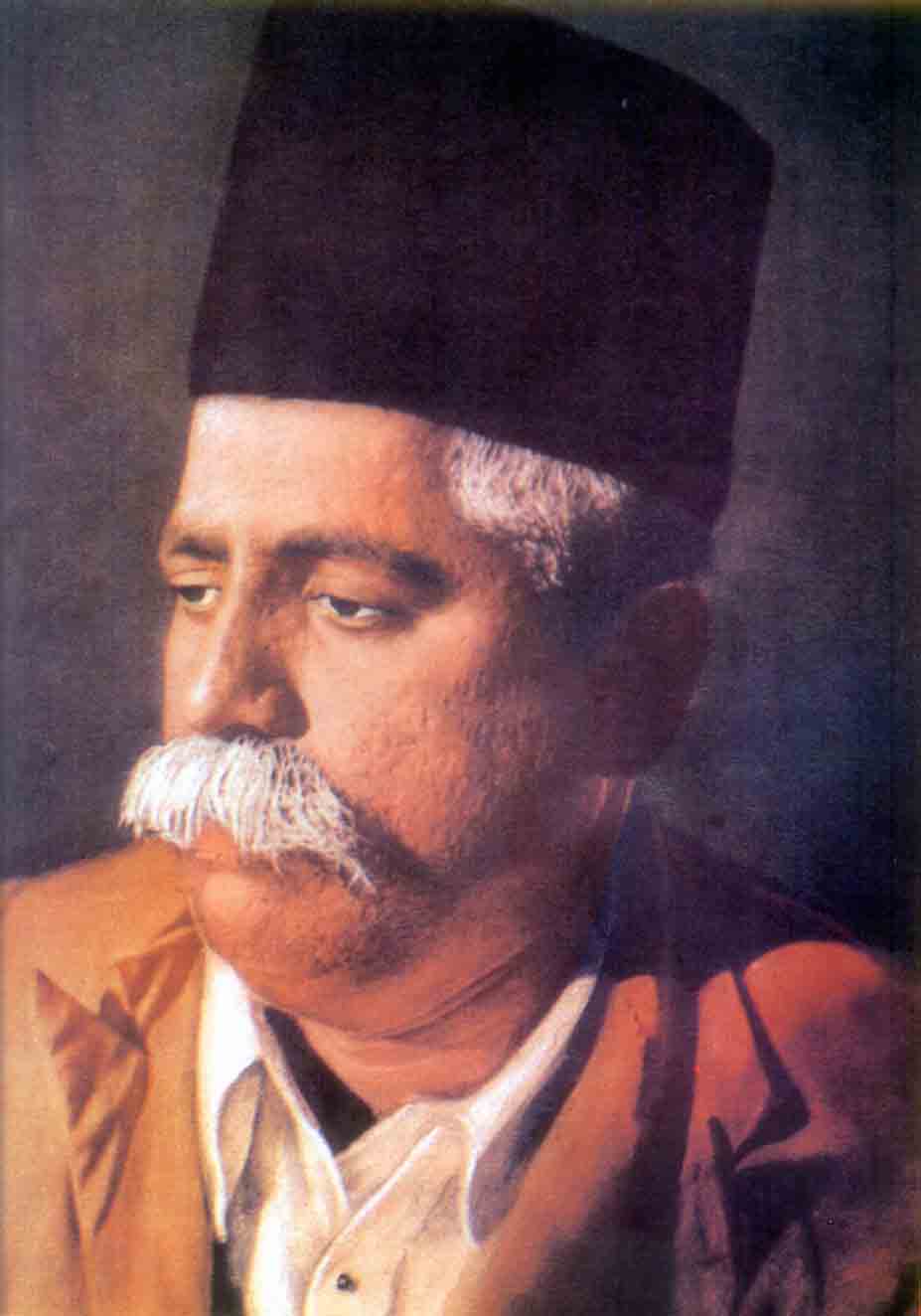

Hegdewar had opposed the British from his school days, for which when he reached college age, he was barred by them from studying in British affiliated institutions. He started the idea of the RSS well before it acquired a name in 1926. Its central purpose was to get the Hindus to form a ‘nation’. He never intended it to be a political organisation. That was to come much later in 1951 when the Jana Sangh was born under the leadership of Syama Prasad Mukherjee. He died two years later.

Before that, however, there was the highly controversial M. S. Golwalkar, revered by the RSS as Guruji. Golwalkar, says Mukhopadhyay, had many facets and was never a political man although he saw the need for political action.

The author says Golwalkar’s observations on the religious minorities, particularly the Muslims, have always been a cause for discomfort in the RSS. Recently, the current head of the RSS, Mohan Bhagwat, distanced the RSS even further from the Golwalkar view.

Syama Prasad Mukherjee is another of the Sangh Parivar’s iconic leaders, but this time a political one, rather than a cultural one. He started handling administration at a very young age in Calcutta University and later became political after joining the Hindu Mahasabha. He served as a minister in a Bengal ministry in the early and mid-forties and joined Nehru’s cabinet in 1947.

But their differences on whether to approach several issues along Hindu-Muslim lines or not could not be reconciled and in 1951 he quit the ministry to form the Jana Sangh. He, too, is held in very high regard by the parivar which, however, prefers to forget that he had endorsed partition although his mentor, Savarkar, had been dead opposed to it.

Once the Jana Sangh had been formed and started contesting elections, the approach of the RSS underwent a change. This happened under the leadership of Balasaheb Deoras who became the head of the RSS in 1973 after Golwalkar passed on.

Deoras, says Mukhopadhyay, was not the typical RSS man. Unlike Hegdewar and Golwalkar, he preferred action to thought and direct intervention in politics to building Hindu character. He was also a strict disciplinarian, practical in his approach and, above all, at least an agnostic if not an atheist.

In 1952 he wanted to be transferred to the Jana Sangh but Golwalkar refused saying he was needed more in the RSS. Eventually, it was under his guidance that the Jana Sangh/BJP became a major political machine. By the end of the 1980s, it had become a major player in government formation and by 1996, it was able to form the government in Delhi. Deoras died in 1996.

Compared to these men – Hegdewar, Golwalkar, Mukherjee and Deoras – the other leaders don’t measure up fully. They were more politicians seeking power than men of ideology seeking to transform Hindu society. Nanaji Deshmukh was the sole exception but he avoided politics and devoted himself to social welfare.

As the 2019 general election approaches its end on May 19, the contents of this book can help the reader understand what lies ahead for the RSS – will it revert to its original purpose of social reform or will it impose its will on the politicians of the BJP.

The RSS: Icons of the Indian Right by Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay; Tranquebar; Rs 799

K. B. Hegdewar started the idea of the RSS well before it acquired a name in 1926. Its central purpose was to get the Hindus to form a ‘nation’. He never intended it to be a political organisation Picture credit: Wikipedia