The Fractured Himalaya: India Tibet China 1949-1962

By Nirupama Rao,

Viking, Rs 999

If India had a government which valued talent and experience, Nirupama Rao would have been in the thick of diplomatic negotiations or at least giving advice to the negotiators on how best to deal with China on India’s border troubles in Doklam and, later, in Galwan, which have successively plagued bilateral relations since June 2017. It is fortunate for readers and reviewers that Rao is instead writing books and expanding on the ideas in her books at think tanks and other fora where her recent scholarly work on Sino-Indian relations, The Fractured Himalaya: India Tibet China 1949-1962, is the subject of many illuminating discussions.

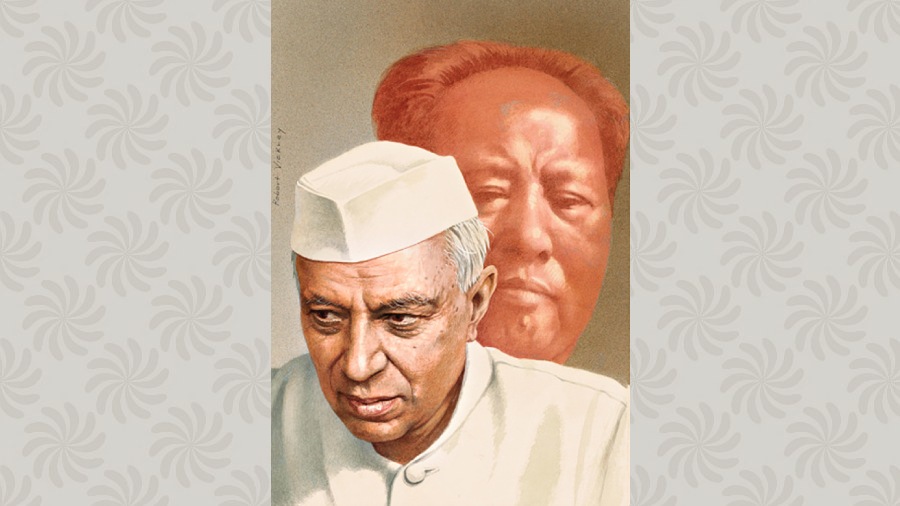

Rao has done a great service to someone like this reviewer, brought up in school to admire Jawaharlal Nehru and now confused by the criticism of the first prime minister, especially for his handling of China. To future generations too, by bridging the historical divide between those who condemn Nehru for India’s 1962 military defeat in the border war and others who find excuses for the folly.

Citing examples in the evolution of India’s China policy from Mao Zedong’s assumption of power until the sorry end of the ‘Hindi-Chini bhai bhai’ era, Rao elevates Nehru’s mistakes to those made by others like him before elsewhere in the world. The United States of America, for instance, was secretly warned of a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, but it was ignored and kept a secret for many years. Josef Stalin should have known better than to trust Adolf Hitler and agree to a non-aggression pact in 1939 between the foreign ministers, Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov. And, alas, the less said about the failed appeasement of Nazi Germany in 1938 by the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, the better.

Like these colossal errors of judgment in history, the message in Rao’s book is the old adage that ‘to err is human’. Nehru erred too. But did India learn anything from the costly errors of the first prime minister in the decades that followed? Such a spin-off will remain incomplete unless the author pens another well-argued book answering this question. Rao is eminently qualified to do so because she was deputy secretary, director and then joint-secretary dealing with China in the ministry of external affairs for eight continuous years. Later, she was ambassador in Beijing and, subsequently, as foreign secretary, she was hands-on with the China policy of the Manmohan Singh government.

The book is sprinkled with tales, which evoke fantasies of Shangri-La and an overflow of engaging episodes that lay readers have no access to otherwise because they lie buried in vast archives in many countries. One such episode bears narration, if only because it opens windows to how today’s Belt and Road Initiative came about and the Chinese leadership’s foresight about the danger of radical Islam 70 years ago.

After the British vacated partitioned India, Pakistan asked for the United Kingdom’s consul general in Kashgar in the Xinjiang region to remain at his post for a year, but as Pakistan’s representative there. The Briton lived in ‘Chini Bagh’, the Indian consular residence in Kashgar. Pakistan’s ploy was to lay early claim to the (British) Indian post and property. Pakistan was also conscious of Xinjiang’s long-term religious and strategic importance. Rao writes that contrary to Pakistan’s game plan, “there is little to suggest that the maintenance of the office in Kashgar occupied the Ministry of External Affairs in Delhi at any length.” When it came to continuing trade along the Silk Route, “a trade treaty with China on India-Xinjiang trade was rejected by the Commerce Ministry in the government of India.” The author notes with regret that such opportunities were not pursued and a new political geography has emerged along India’s northern frontier with China as pivot as the BRI shows.

One of the most fascinating dramatis persona in early Sino-Indian engagement to emerge from the book is Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, who led the first Indian cultural delegation to China in April 1952. Pandit was prophetic then in saying that Chinese hatred of “American aggressors and imperialists” was pretended “just to keep up the public morale.” How true she turned out to be in the 1980s and ever since, as China adopted the best practices of the US and adapted to them to grow into the superpower that it is destined to be.

By being modest about her personal part in crafting the MEA’s China policy even when she was out of the China desk — the former national security adviser, Brajesh Mishra, insisted she should be part of border negotiations although she was then additional secretary (administration) — Rao has laid some of her assertions in the book open to question. Despite such lacunae, The Fractured Himalaya is essential reading for anyone who is interested in how Sino-Indian relations were shaped in the first decade of India as a republic.