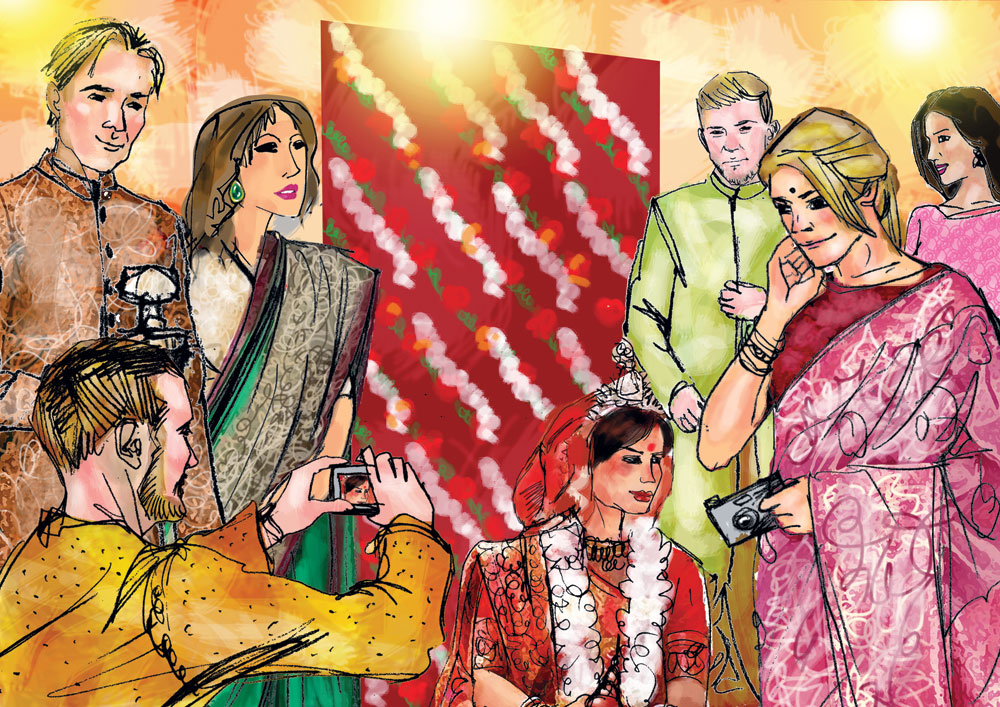

Golden light rained down from the chandeliers. The cutlery, perfectly aligned on the round tables below, caught the refracted rainbows. A soft shehnai played, as though very far away. There was a profusion of pink flowers everywhere.

“Look at that waist,” sighed Kulkul, “Same as what it was in her youth.”

“Naturally,” replied Kulkul’s mother-in-law, Manjulika’s cousin, Lata’s Shumu Mashi, who had come to attend Molly’s wedding from Nabadwip. “That slim waist hasn’t had to deal with childbirth, na. Motherhood ravages. Munni’s body is unscathed, so naturally it is perfect.”

“Shhh,” said Tinku, Kulkul’s husband, the youngest product of Shumu Mashi’s multiple ravagements, sitting self-consciously erect at the table. Tinku’s suit was jaunty, his collar was stiff, and the dry-cleaning liquid had given him a rash that now bloomed underneath. “Please don’t say unseemly things, Ma,” he said tightly, “Munni Didi has been extremely kind to us always.”

“Easy to be kind,” said Kulkul, now attempting to attract the attention of a waiter, who hovered at the next table and resolutely refused to look her way, “when you live in London and America and come to Kolkata for five minutes in five years. Has she ever invited us to London? Okay, maybe not us. But when Mou went to Finland, why did she not invite her home?”

“Right, Finland and England are Ballygunge and Tollygunge,” Tinku said, his face impassive.

Having built the foundation of her married life on the assumption that her husband’s irony was, in fact, agreement, Kulkul now turned her attention from Lata to her daughters, who were wandering about the banquet hall in their five-star-wedding finery, taking photographs on their phones. “Aahaa re, they must be feeling hungry,” she now mused. “Where is all the five-star food?”

Lata Ghosh, who had accidentally-on-purpose overheard this conversation, now took her unravaged-by-motherhood waist, swathed in the tea-green Benarasi with its gold-leaf border — the sari she had not been able to resist buying despite its five-figure price — over to the banquet manager.

“Prasad,” Lata wagged her finger at him, “what was our deal?”

The gold in Lata’s earlobes winked. Prasad melted. “I am trying, Madam, trying.”

“Trying is not enough. Please instruct your boys. While all the snacks should be rotated around the hall, the fish fingers with mango-mayo relish and the galouti-pitas must be available at all times by the Bengali tables. The chaat-kits must be circulated round the clock at the Jaiswal tables. The guests are getting restive. Indian weddings are remembered by their food. It doesn’t matter that you studied hotel management in Switzerland, (Prasad had, in fact, studied at Taratala, but Lata’s assumption made him puff up like a bull-frog) the food must make a mark. Go to that table yourself (it wasn’t difficult to pick out Kulkul’s aubergine Kanjeevaram in the crowd) and ask them what they need.” Lata sweetened the instructions with well-timed smiles. Invigorated, Prasad rushed over to Kulkul’s elbow.

“Where is my mother? Why isn’t she keeping Shumu Mashi company?” Lata wondered aloud to no one in particular as she helped herself to a fish finger. It was 7.30, and there was still no sign of Aaduri who had promised to arrive early. Having been on her feet since the morning, Lata now felt exhausted.

At some point in the next five minutes, she knew she must go to the adjoining hall and check upon the shubho drishti arrangements. She didn’t know who she should be more annoyed by. Aaduri had sent a painfully young reporter called Tiana with a photographer in tow to “cover” the wedding. Or Goopy? Who was avoiding the relatives and sitting with AJ and Kaku, devotedly following the rituals. She brushed off the crumbs annoyedly.

She knew she should go and flutter about the Nabadwip relatives a bit — they were touchy and liable to feel insulted if proper attention was not paid to them — but she also did not know what to say if quizzed about her life goals.

Ugh.

Suddenly seized with an idea that might kill two birds with one stone, she briskly strode up to the gigantic flower arrangement at the centre of the banquet hall, where Kulkul’s two daughters were busy taking selfies.

“Girls,” exclaimed Lata, “You look lovely!”

“Lata Pishi!” said Koli, the eldest, “When did you come from London?”

“A month ago, sweetie,” Lata replied, “I have just the job for you two now. Come with me.”

At 16 and 14, Kulkul’s daughters, in their pink-and-gold anarkalis, round golden spectacles and newly-plucked eyebrows were adorable, all limbs and awkwardness. Lata marched them to the dais and stationed them on either side of Molly. “Your job is to take the presents from Molly and pile them up carefully. Koli, since you are older, any jewellery or envelopes, you keep them carefully in this bag. Okay?” The girls nodded seriously. “And smile,” said Molly, pulling the cheeks of the younger one, “You’re going to be in all the photographs!”

“How’s AJ holding up, Didibhai?” Molly now twinkled at Lata.

But before Lata could reply — AJ was doing wonderfully and his salmon pink sherwani was apparently a hit with the Bongs — Koli poked her, “Lata Pishi, is that Pragya Paramita Sen? Oh my god, oh my god, I have to Insta this right away!”

At the far end of the hall, Lata now found a slim creature in a gorgeous green silk sari, wavering, looking about herself uncertainly. She was followed by a minuscule entourage, two people, but there was no sign of Ronny. “I better go and greet her,” said Lata. “Don’t abandon your spot in your enthusiasm, girls. I shall bring her here instead. The photographer shall take pictures. But please Be Cool.”

As she walked up to young Pragya — who, fortunately, hadn’t been spotted by Kulkul yet and who stood charmingly waifish by the gigantic door — Lata wished she had reapplied her lipstick after chomping that fish finger. It was all great, just great. This chit of a girl would be spat out by the film industry after a movie or two. Obviously. She and Ronny would then marry. They’d have an adorable kid, maybe two. Ronny’s film-making career would soar. Meanwhile, Lata would live and die alone in London and leave her property to Molly’s kids. Great. Just great. Hang on, wait, shouldn’t she leave her property to a charity though?

“Hello, hello, you must be Pragya,” said Lata, extending her hand, “So lovely to meet. I am...”

“Charulata, I know,” said Pragya, “You were with Ronny in college.”

“A hundred years ago,” said Lata, “And you are...”

“Mimi’s my cousin but she’s also managing my social media these days,” Pragya explained, “And this is Clay. He is an Indophile.”

“I believe Ms Bagchi is covering the wedding exclusively?” Mimi asked.

“Yes, I do believe so. Come, let me introduce you to the bride, after that I shall hand you over to Bobby. She’ll know all about that,” Lata said, and began to shepherd the group towards the stage.

These showbiz types can’t attend a wedding without publicity, Lata mused. Anyway, apparently she was the only old-fashioned one getting annoyed at this. From Molly to Manjulika to Aaduri, everyone was excited about the exclusive wedding coverage.

“What time is Ronny going to get here?” Lata asked Pragya, maintaining a studied neutrality in her voice.

“He said around 7.30,” Pragya replied, “but...”

“Oh yes,” smiled Lata, “with Ronny that could mean 8.30 or 10.30 or 7.30 tomorrow morning.”

Pragya laughed. It was a pleasant, tinkly sound. Lata tried to imagine Ronny listening to this tinkly, wind-chimey laughter all his life. Bloody fool.

“Hello,” said Molly, coolly.

“You look lovely,” said Pragya. “I feel embarrassed about coming empty-handed. But Ronny’s bringing our present.”

But, of course, they would give a present together.

“Molly, it’s time for the shubho drishti.” Looking stunning in a white-and-gold Dhakai, Manjulika appeared on the dais from nowhere. “There you are, Munni,” she said, ignoring Pragya. “Let’s proceed to the antechamber now, shall we? The piri is ready.”

“But,” said Molly, “But Mejo Jethi, I promised to wait...”

“There is no time, Molly, come on,” Manjulika rushed them all.

The girls trooped behind Manjulika and made their way to a little connecting room from where Molly would be carried to the faux chhadna tala. Molly sat down on her piri, Pragya made small talk, the Germans took photographs.

“Munni, will you come here for a moment?” Manjulika asked.

Lata followed her mother back into the banquet hall. Kaki was standing there with an urgent expression.

“Who all will carry her?”

“Well, Goopy, of course,” said Lata, “And Duma, naturally.”

“But if the Jaiswals ask...”

“Don’t worry about that, Kakimoni,” said Lata, “and Hem?”

“Oh there you are!” Manjulika exclaimed, her voice shot with relief. “I really thought you weren’t going to come on time.”

“Of course I would,” replied Ronny, “I told Molly I would be one of the piri-lifters. And Aaduri’s young man is here too. Hem... I met them downstairs.”

(To be continued)

Recap: As Molly goes through her gaye holud, Bobby who arrived at Ghosh Mansion with the trousseau-bearing Jaiswals, tells Lata that Pragya, who has no link to the wedding, would be there for it. Pragya, meanwhile, consults her mother on what to wear.

This is Chapter 32 of The Romantics of College Street, a serial novel by Devapriya Roy for t2oS. Find her on Instagram @roydevapriya or email her at theromanticsofcollegestreet@gmail.com