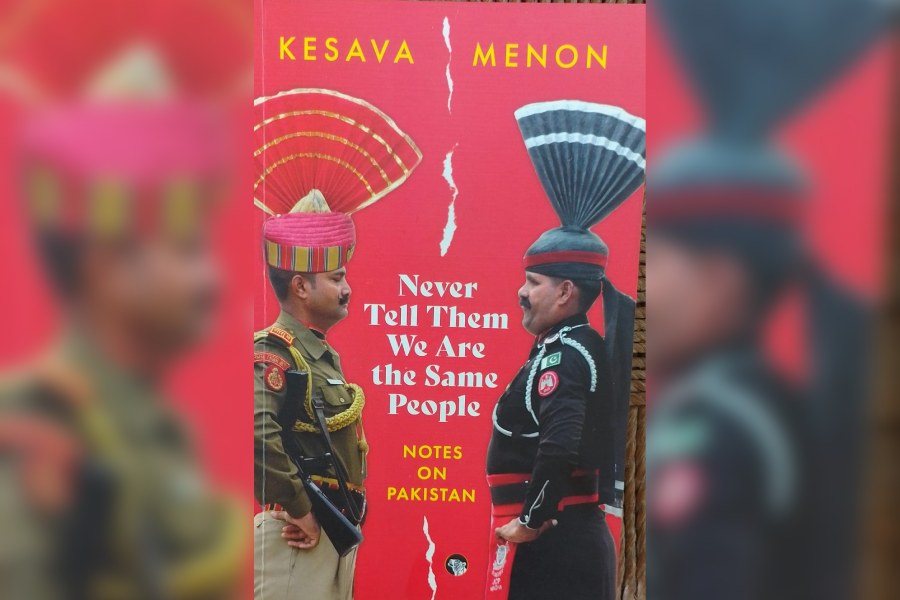

Book: Never tell them we are the same people: Notes on Pakistan

Author: Kesava Menon

Publisher: Speaking Tiger

Price: Rs 399

It is unusual to find a book of reflections on Pakistan, written by an Indian journalist well-nigh 30 years after he lived there. It nevertheless captures accurately the myriad nuances of civil society there and the complexities history has contributed to the vexed India-Pakistan relationship. This book comes at a moment when tumultuous events are threatening to challenge the very tenets of security and ideology laid as groundwork by the self-appointed `guardians of the State’, to keep the country ticking.

The book encapsulates also, the dilemmas confronting a young man of `Malabari Keralite’ origin, albeit having experience of working in `northern Punjabi’ environs (covering the Khalistani Kashmir militancy beat), embarking on a daunting phase of his career.

Kesava Menon arrived in Islamabad in May 1990 as The Hindu’s first correspondent in Pakistan. He remained there till October 1993. As he points out in pages 18-19, his posting was an outcome of `a tedious process --- the two governments had come to an agreement that each would allow three media outlets from the other to operate within its territory.’ Though Dawn backed out from coming to Delhi, `the Pakistanis told The Hindu that it could come anyway’.

Unfortunately, this arrangement no longer prevails today, depriving both countries from getting a ground-level feel of whatever is happening in the other land.

I had the privilege of knowing Kesava and his wife Nandini from close quarters as the first year of his tenure with my own stint at the Indian High Commission, Islamabad. So I can vouchsafe for the splendid work he did, effortlessly settling into the role, proving to be an asset not only to his newspaper then, but afterwards as well, acquiring the reputation of having performed a difficult job well. Ever since, Menon has remained a well-informed observer and analyst of developments in Pakistan.

Kesava’s book is structured into portions where he starts his sojourn from an ambience of `loathing and curiosity’, going on to share surprising incidents like when he had a ` a boar at breakfast (!)’, courtesy his generous landlord in Islamabad, Pir Nazakat Shah. He then discusses Pakistani civil society’s efforts at `forging an identity’, different from India’s. Kesava tellingly flags the advice he received from one of India’s most respected Pakistan watchers, Rajendra Sareen, `never to tell them we are the same people’, which phrase forms the title of his book.

Menon goes on to narrate his interactions with Pakistan’s `flame carriers’ (an euphemism for notorious India-`haters’). These include people like Majid Nizami, owner of the Nawai Waqt group of newspapers, Dr. A. Q. Khan of Pakistan’s `nuke’ fame and the ubiquitous Lt. Gen (retd) Hamid Gul, just retired at that time from the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) but very much hand-in- glove still, with Pakistan’s `non- state’ sponsorship of terrorism into India.

Experiencing `differences’, Kesava comes to terms `living with the enemy’, later `encrusting’ this `enmity’, during the `Rakesh Mittal episode’ (the expulsion of the Indian counsellor at the high commission after violent manhandling and torture) and afterwards. Menon shares twin feelings of trepidation and excitement in course of travels, with his spouse to Mohen jo Daro in Sindh, and the idyllic Swat valley, where despite being followed by the `awami’ (pyjama)-clad intelligence officials he could still interact, rewardingly with ordinary villagers.

It is common for Indian journalists to be suspected by Pakistani intelligence agencies of being tools of Indian intelligence, despite the extra caution invariably exercised not to be so misunderstood. Kesava narrates vividly his own predicament connected to the Mittal episode (Pgs 203-204).

Thefts and provocative intrusions into the household were also common travails which had to be stoically faced. `A turning of the other cheek was not an option available’, a tormented Menon recalls, ` if they did, their tormentors were certain to double down’. Provocations `would continue until our man lost his cool…’. This was par for the course, almost, `the downward spiral would continue’, `being dubbed an agent provocateur..,’`before the machinery slowly ground him to pulp’…. in `a slow suffocation of self-respect’(Pg 209).

It redounds to Menon’s credit that after all these years he dispassionately dissects the Pakistani ethos witnessed then with empathy. He confesses (Pgs 28-29), he `might not have unknotted two separate cultural processes working towards the development of a Pakistani narrative and therefore identity’… 'One is a people’s attempt to arrive at self-realisation by drawing on their history, their capabilities and their hopes for the future’.

The `second strand’ Menon flags, `peculiar to Pakistan, is the pressure applied by organs of the state to compress a natural process into a pre-set mould.’ Pakistan’s `misfortune’, Menon suggests correctly perhaps, is that `the official storyline’ was `never seriously and publicly challenged’, by democratic forces, be it under Zulfiqar or Benazir Bhutto, and then, Nawaz Sharif, who in his later incarnations at the helm of power, did try `to wrest power from the sponsors of this narrative’.

Though `not directly acquainted with a single Pakistani military man’, Menon finds `members of this class’.. `better educated than most of their compatriots’..with `the military allowing itself a mental breadth and depth it denies to the rest of the country’ (Pg 33), striving `to control the national mind’. This is not `merely an analytical postulate’, `efforts made for this purpose flow from the right, duty and status the fauj claims for itself’, as guardians of Pakistan’s ideology.

In an effort to contemporise his work, Menon dwells on some of the more significant changes that have occurred in Pakistan after he left, such as the emergence of a new middle class, the impact of a youth bulge, the changing patterns of recruitment into the Pakistan Army and the vibrant, `attention- grabbing’ electronic media, which seems more `empowered’ today, than their `godi’ counterparts in India (pages 226-227).

In an `afterward’, Menon also comments on the military’s most recent `hybrid’ experiment of foisting Imran Khan on the country, as` a politician who could be marketed as a change- maker’. Sadly, Imran proved `incapable of seeking the good of anyone other than himself’, making `disastrous’ `choices in personnel and policies’, and his family/ entourage `seemed as incapable of keeping its hands off the public wealth as any that had exercised power before’. In fact, Menon wonders tongue-in-cheek, why `the generals took so long to catch on (Pg 230).’

Though the absence of reference notes and a bibliography detract value somewhat, Menon’s book is a delightful read and serves as a veritable treasure trove of valid analytical perceptions for avid Pakistan watchers in India.

Rana Banerji was a special secretary in the Cabinet Secretariat