Book: Thunderclap: A Memoir of Art and Life and Sudden Death

Author: Laura Cumming

Publication: Scribner

Price: $32.50

The colour of the Dutch golden age was a distinctly dull brown. In spite of its artistic brilliance, the primary focus of the age seems to have been on the mundane — still lifes of household goods and exotic imports from foreign lands, marking the beginning of both colonialism and capitalism (Still Life with a Nautilus Cup by Willem Kalf); neat and richly decorated interiors, often with women hard at work (Interior with a Woman by Emanuel de Witte); landscapes depicting vast flatlands with low horizons and powerful stretches of the sky (Landscape with a View of Harlem by Jacob van Ruisdael); and Tronies, bust-length physiognomic studies of human ‘types’ not meant as individual portraits (Girl with a Pearl Earring by Johannes Vermeer), made up the bulk of the artistic output of the age. Scholars and critics alike have maintained that these are not exercises in invention so much as attempts at ‘transcription’.

But to the art critic, Laura Cumming, there is magic in the mundane. For her, these works are “sacraments, or hymns to everyday existence.” Some of the most insightful passages in this book concern the obscure still-life artist, Adriaen Coorte, who specialised in paintings of fruits or vegetables isolated on the same ledge, their forms surrounded by utter darkness. The Dutch artworks are, Cumming concludes, “a land in themselves, a society, a place to be.” Thunderclap, then, is her attempt to inhabit their strange and sublime domain. To do so, she zeroes in on Carel Fabritius, an enigmatic painter often described as the ‘missing link’ between Rembrandt (in whose workshop he apprenticed) and Vermeer (who owned three of his works). Fabritius’ life story forms the trail of breadcrumbs that Cumming follows into the lustrous interiors that are instantly recognisable from the works of the Dutch masters, with their snowy tablecloths, jugs of milk, dozing dogs and serene maidservants.

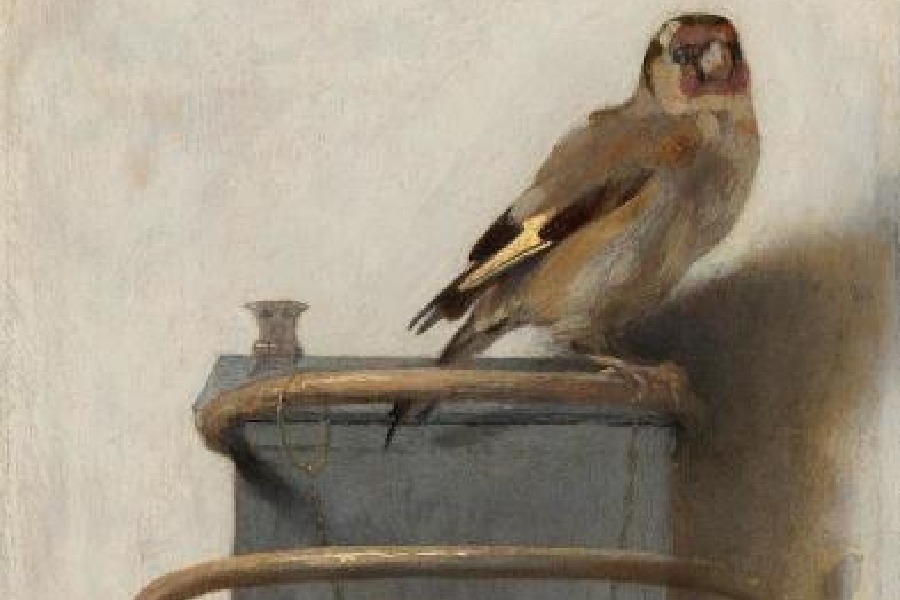

The tranquil does not last long though. In 1654, a gunpowder store exploded in Delft — home to most of the Dutch masters — taking a quarter of the city with it. Fabritius was just 32 when his home collapsed around him in the explosion and any work other than the dozen or so pieces now attributed to him also disappeared with him. All surviving accounts of his life chronicle loss — married at 19, Fabritius ended up burying his wife and the three babies she bore him by the time he was 21. A second marriage seven years later produced only a trail of debt. Cumming’s reading of these losses and the grief-stricken withdrawal in Fabritius’ works is poignant. A View of Delft, With a Musical Instrument Seller’s Stall is what first drew her to Fabritius, not for its radical experiment with perspective but for the figure of the instrument seller who “remains forever on the outskirts” of the scene, brooding alone in its shadows. Even the solitary bird in The Goldfinch — a startling discovery about this painting marks the book’s climax — which is forever imprisoned by the chain that fixes it to its perch, speaks to Cumming of isolation and inwardness.

The author is no stranger to these feelings. She felt loss and loneliness acutely and up close when her father, the famous Scottish artist, James Cumming, passed away at the age of 68. His death, after a long battle with cancer, was, arguably, less unexpected than that of Fabritius. But death, Cumming shows, always feels both sudden and random to those it leaves behind. Her book is an elegy for both Fabritius and her father and all those other Dutch painters with whom she associates their memories.

Thunderclap is not art history of the academic kind — there are no footnotes or references to sources beyond Cumming’s own feelings and intuition. At its heart, it is about the capacity of art to make us see life for what it actually is.