Book: Love, Exile, Redemption : The Saga of Kashmir’s Last Pandit Prime Minister and his English Wife

Author: Siddharth Kak and Lila Kak Bhan

Publication: Rupa

Price: Rs 695

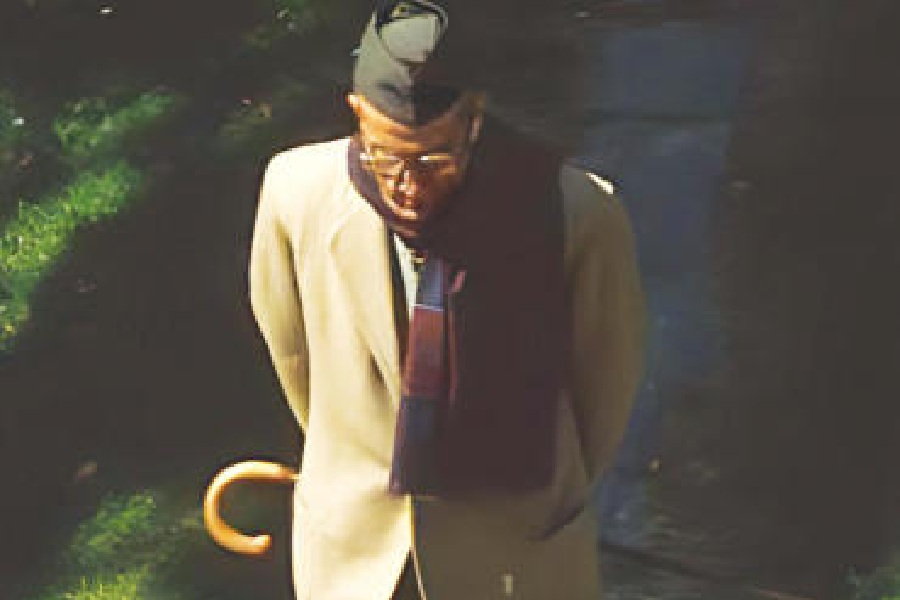

Ram Chandra Kak, one of the few Kashmiri Pandits to hold the prime minister’s post of Jammu and Kashmir (June 1945-August 1947), had to negotiate the unenviable task of navigating his state through the unsettling times of the transfer of power from the British raj to the nascent dominions of India and Pakistan. Kak’s impeccable political stand during such troubled times was further challenged by the turbulent activism of the political parties from the state like the National Conference and the Muslim Conference. Siddharth Kak and Lila Kak Bhan’s biographical tribute faithfully reconstructs these socio-political and personal circumstances, which also shaped and directed Ram Chandra Kak’s political destiny, in some detail. Based on hitherto unpublished memoirs, diary jottings, letters, interviews and other forms of recordings, the volume dispels myths and erroneous perceptions about the former prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir.

The most engaging sections of the book meticulously trace the partisan agenda, personal ambitions, parochial dreams, and political intrigues of the time — often demystifying some of the hallowed political personalities of the period. The following chapters, “Becoming Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir”, “A Political Game of Chess”, “Pandit vs Pandit” and “Reaping the Whirlwind”, are bound to engage the readers. Through a detailed narration of Ram Chandra Kak’s steadfast negotiations upholding the primary interests of the state, readers are provided with an incisive analysis of the political circumstances that shaped the controversial history of contemporary Jammu and Kashmir. Kak’s spirited defiance against the onslaught of persistent manoeuvrings of giant personalities of the day, such as Lord Mountbatten, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Jinnah, Maulana Azad and Sardar Patel, is definitely one of the astounding revelations of the book. Citing from his unpublished memoir, Kak and Bhan underscore Ram Chandra Kak’s sheer resilience in warding off incessant waves of extreme political clout and pressure directed at forcing allegiance: “… I told Mahatma Gandhi that I refused to accept a position where one authority, in this case the Congress and its leaders, were to dictate the policy and another authority, in this case the Kashmir government of which I was the head, were to bear the consequences of that policy.” Ram Chandra Kak’s decision to fiercely defend the neutral stand of Kashmir was firmly rooted in the socio-political reality: “Bhaiji [Ram Chandra Kak] knew that any decision based on religion would ignite violence, as both Hindu and Muslim communities lived side-by-side and coexisted more or less peacefully in the state, so long as their religious identities were not threatened.” He even persuasively countered Jinnah’s lucrative offers and coaxing, firmly opposing Kashmir’s acceding to Pakistan in no uncertain words: “Consequently, I said, we had come to the conclusion that not only in our own interest but also in the interest of both India and Pakistan, it would be best for us to remain outside, though in [a] close and friendly relationship with both.” The chapter, “Pandit vs Pandit”, is a crucial section of Ram Chandra Kak’s memoir in which he shares the compulsions and the constraints that ultimately led to the detention of Nehru on June 21, 1946. This episode is aptly summed in the book: “Bhaiji’s first year as the PM ended with an event in June 1946 which has become notorious as the clash of two most unequal forces, when the pygmy PM of a princely state dared to defy a colossus of the Congress and the future PM of India.”

The political memoirs of Kak, coupled with the personal diary jottings of his English wife, Margaret Kak née Allcock, are bound to put the fictitious narratives looming on the Partition to rest. The lucid narration of various anecdotes in the book is brilliantly recreated through the illustrations of Kashmira Tembulkar, imparting a unique dimension of elucidation to the biography.

In its reconstruction of the events of the turbulent times, Love, Exile, Redemption brilliantly traces the multiple circumstances and vicissitudes that ultimately contributed to the scripting of the twentieth-century history of Jammu and Kashmir. The long chain of these developments included complex, behind-the-scene intrigues: the appointment of Swami Sant Dev as Rajguru during the time of Maharaja Pratap Singh, Swamiji’s subsequent banishment from the court by the agnostic Hari Singh, the role of Maharani Tara Devi (Maharaja Hari Singh’s wife) in palace politics (in connivance with the erstwhile banished Swami), Hari Singh’s increasing loyalty to the Swami’s beguiling prescription of an extended empire of Dogristan (notwithstanding Kak’s strong disapproval of the envisaged new Himalayan kingdom, including Tehri Garhwal with the Maharaja of Kashmir as suzerain). Against such a backdrop of turmoil, struggle, incarceration, release, exile and return to the Kashmir Valley, Siddharth Kak and Lila Kak Bhan also manage to provide a unique insight into other aspects of the dynamic personality of Ram Chandra Kak. His pioneering efforts as an archaeologist deserve special mention in this context.

This book is bound to draw the attention of historians and general readers alike, especially those interested in mapping the divergent socio-political drifts and cross-currents that contributed in shaping the history of Jammu and Kashmir.