Book: The Philosophy Of Modern Song

Author: Bob Dylan

Publisher: Simon and Schuster

Price: $45

This is Bob Dylan’s first published book since winning the Nobel Prize in 2016. It advertises itself as a treatise on music, with possibly an ironic reference to Theodor Adorno’s Philosophy of Modern Music. While Adorno’s book is a complex, philosophical engagement with modern (classical Western) music, Dylan’s is a series of short pieces, musings and riffs on a number of songs from the second half of the twentieth century. These songs belong mainly to the blues, country, or rock and roll traditions. Crooners loom large. The sixty-six songs described in the book do not purport to constitute a comprehensive survey of the ‘modern song’. Of course, one may question some of the choices, wonder why there aren’t more songs by women (four in all), feel that The Beatles should have been part of the ‘modern song’ (Dylan quotes The Clash’s line about “phony Beatlemania”). Taken together though, these songs constitute part of Dylan’s record collection. They are perhaps some of the inspirations for his own compositions, a sample of his tastes. It is a self-portrait in musical references.

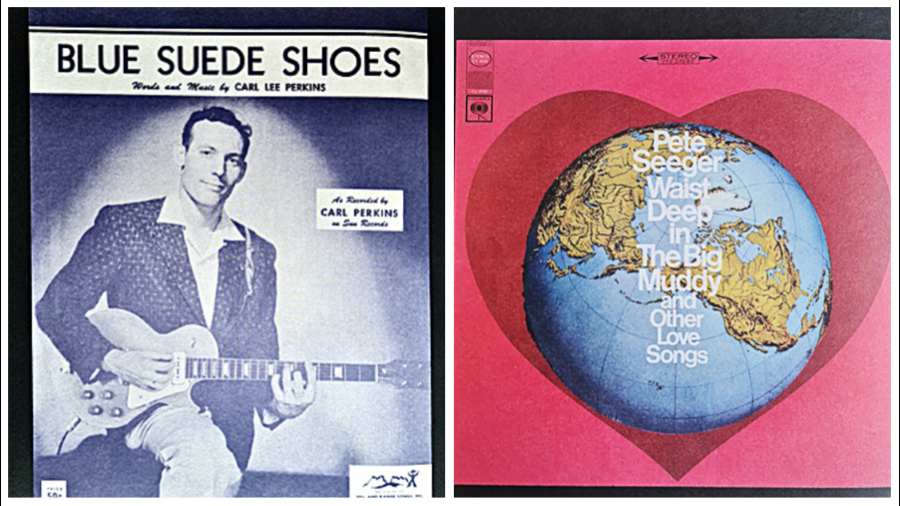

This is a book to be looked at. It is beautifully illustrated with photographs, sometimes by famous artists, weaving a narrative of their own. Some pictures illustrate the songs directly, some others humorously (the chapter on “Blue Suede Shoes” contains an advertisement for such shoes, titled “We’ve Got the Blues”). Photographs of artists or reproductions of the sleeve covers of recordings are inserted in these chapters. A picture of a bayou accompanies “Blue Bayou” by Roy Orbison. Adverts from the era — a photograph of Castro holding a newspaper whose headline is “Plot to Kill Castro” — stills or posters from films, book illustrations, paintings, photographs of record shops, the poster of the reward for Jesse James, and, right after the table of contents, a photograph of women working in a records factory create a rich visual environment in which to experience the songs.

This is also a book to be listened to. It is an invitation to discover songs, or to recall wellknown tunes. It is an itinerary in blues music, telling the reader where to stop. Thirty years ago, readers would have experienced the book differently, wondering how to hear the songs which Dylan talks about. Now, just about every song is a click of the mouse away and we can listen with equal ease to Bobby Bare’s “Detroit City”, which opens the book, as we can reach for the record of The Clash’s “London Calling” on our shelf. We can pick and choose or immerse ourselves in this universe, with Dylan’s voice in the distance.

This is, of course, a book to be read. But in reading, you learn how to listen. Each of the sixty-six songs is an occasion for Dylan to write about the lyrics and the music, to write about the band or similar-themed songs (“The Little White Cloud That Cried” by Johnnie Ray leads into a list of songs with lead singers breaking down in tears), to write about history (the city of Detroit), the geography (the Mississippi river), the literature (Kerouac or Poe), the films (Sunset Boulevard or Rio Bravo) of America. While there are moments in the book which seem more philosophical than others, taken together they provide a story rather than a history, a tale that we are being told by a master storyteller. Sometimes the storyteller suggests ways in which to approach the songs, as in the opening of the chapter on “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me” by Billy Joe Shaver: “This is a riddle of a song, the further you go with it, the stranger it gets, seems to have ulterior motives. Kind of song you don’t see coming until it’s on you.” Sometimes he is more precise in his description of the music: “El Paso is built on five stanzas, each one of two verses and a bridge and then returning to the next stanza. What makes it unusual are the pickup phrases between the end of the bridge and the next verse, short preludes that propel you into the ongoing story.” At other times, he is being playful, or sad. He underlines the contemporary social and political relevance of “Ball of Confusion” by The Temptations; he brings out the belligerence in Elvis Costello; he finds in “Don’t Let me Be Misunderstood” not only the artistry of Nina Simone but also an occasion to reflect on language and art. He seeks, above all, truth and authenticity, earnestness rather than simplicity. He recognises artists at the height of their powers, and the powerful encounter between singer and song.

The last paragraph is about time and music and sums up the philosophy, perhaps not of the modern song, but of Dylan’s book: music “is of a time, but also timeless; a thing with which to make memories and the memory itself”.