Science tells us that evolution has programmed the human mind to dislike certain odours. This explains our aversion to the smell of rotten food or foul chemicals. But biology is not the only thing that informs the human revulsion for all that is malodorous. More often than not, the reasons that lead us to crinkle our nose in disgust are sociological.

This is what led Allison Breed to start the ‘Male Scent Catalogue’ on Twitter. In it, Breed examines the smell of men and women in romance novels. Breed realized that women always smell like sweet-smelling flowers or strawberries or baked goods — basically, something edible, delectable or decadent. Men, on the other hand, emit a wider variety of scents. While all of them give off a scent that is ‘masculine’ — what does that even mean? — this is embellished with added aromas, ranging from ‘steel’ and ‘bonfire’ to ‘leather’ and ‘whisky’. Class and career, Breed found, influence the way a romantic hero smells: working-class men tend to smell clean and soapy — cleansed of the smell of their labour — whereas billionaires reek of expensive cologne.

Breed’s findings, though, are not novel: odour and the Other have always been intricately linked. Socrates was of the opinion that “[i]f you perfume a slave and a freeman, the difference of their birth will produce none in the smell... the odour of honourable toil... is ever sweet...” Socrates may have caught the sweet whiff of hard labour, but not W. Somerset Maugham. Born with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth at the British embassy in Paris, Maugham grudgingly admitted, “I do not blame the working man because he stinks, but stink he does...”

Honourable toil or not, the aroma of ‘the great unwashed’ did not sit well with many. The Bard, for instance, seems to have had an acute sense of smell, and almost certainly shared Coriolanus’s disgust for the “rank-scented many” and their “stinking breaths”. But Shakespeare, like many others with the means, had at his disposal an array of strong perfumes — and not just the ones from Arabia that Lady Macbeth craved either — to get rid of odour, real or metaphorical. The most fashionable ones were musk, ambergris and civet.

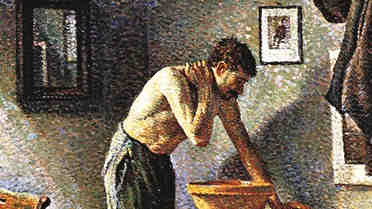

The poor did not have the means to smother what the socially advantageous thought was their stink. They even lacked access to amenities that were then luxuries: soap and hot water. Evidently, the Elizabethan working-class romantic hero would have not smelt clean and soapy. Smell as a marker of differentiation has had a long afterlife.

But this instrument of distinction — discrimination — was built on myth. George Orwell was taught early in his life that ‘the lower classes smell’. It was only later in life that Orwell realized that “you acquired the idea that there was something subtly repulsive about a working-class body”.

This is where biology becomes fused with, and even triumphs, morality. The inhalation of foul odour produces an immediate physical revulsion. To characterize a group of people as foul-smelling is to render them repellent at a physical level, even before the question arises at a cognitive and moral level. Orwell got it right when he said: “Race-hatred, religious hatred, differences of education, of temperament, of intellect, even differences of moral code, can be got over; but physical repulsion cannot