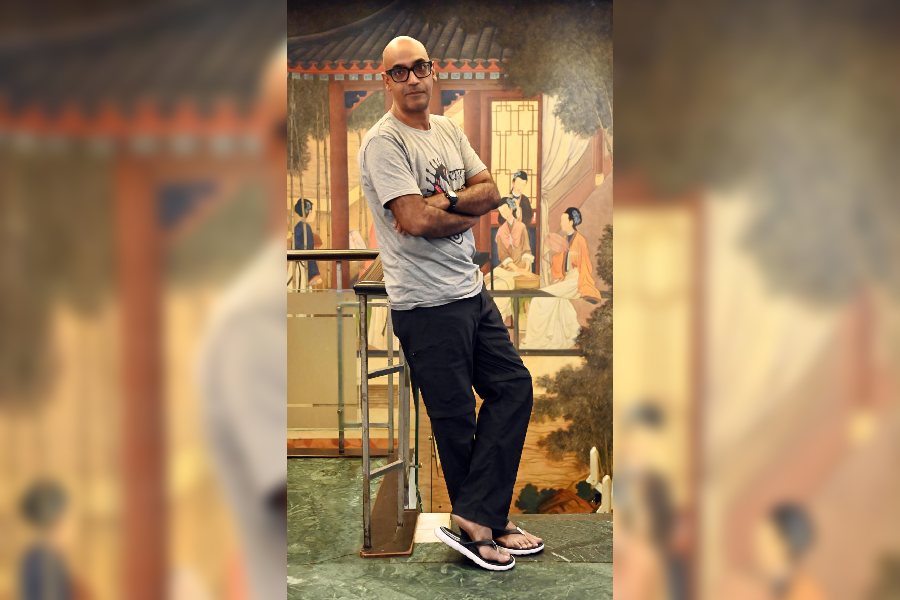

With The Light at the End of the World, Shillong-born and New York-based Siddhartha Deb brings four stories, making the readers visit the dark past with his characters. This is Deb’s first novel in 15 years and with it, he also delivers an ode to Calcutta, the city that he grew up, fell in love and kicked off his career in. A tete-a-tete with the novelist who uses magic realism and is creating a new fiction off his craft.

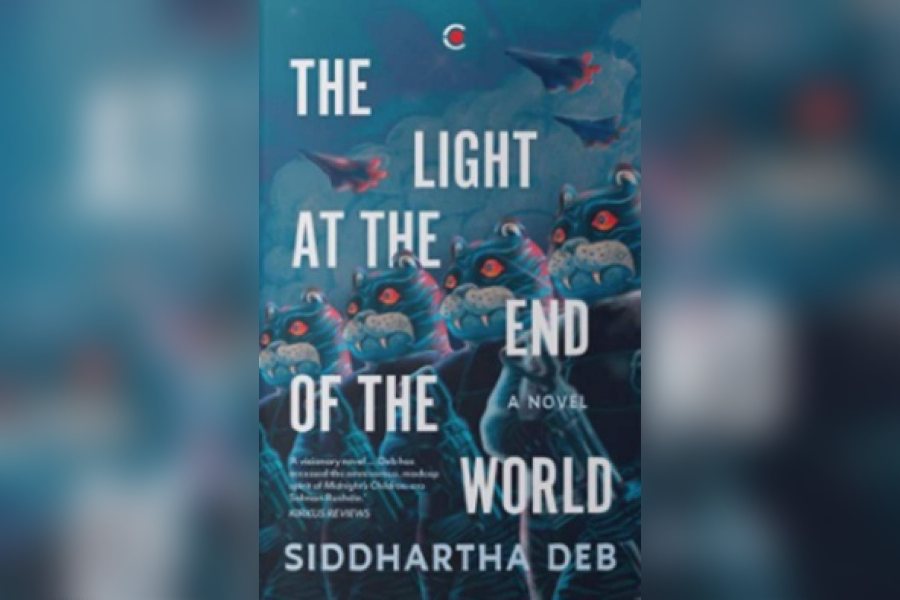

The Light At The End of The World by Siddhartha Deb; Published by Westland Books; Price Rs 799

What is it that took the book so long to write?

It’s a big complex book and I wanted to write an Indian novel that was different from what I have written in the past. I wanted to write something that I felt could, on one hand, speak of our times but in an angular way, and could push the literary convention of realism. The novel plays a lot with speculative fiction, occult and ghost stories and I wanted to bring in things that sometimes are not taken seriously in English writing but are part of our diverse folk cultures.

A review comparing your book with Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children finds space on the cover of the book. What does this comparison mean to you and how much has Rushdie influenced your writing?

I have been a great admirer of Rushie’s earlier writings, especially Midnight’s Children. So, to me, it’s very flattering to be compared to Midnight’s Children. Also, I think a lot of reviewers have been very generous. They’ve also compared it to Gabriel Garcia Marquez…. And I think in America particularly, they’ve all been very good but they’ve had a little trouble figuring out where to put me as this book is different. Sometimes they are comparing me to American writers like Octavia Butler and Robert McCarthy. And I think that’s a good comparison because I’m not just in conversation with South Asian writers including Bangladeshi and Pakistani writers but I also read Latin American and African American writings. So this novel is kind of influenced, inspired by those things as well.

Calcutta’s The Telegraph’s reviewer called your novel ‘weird fiction’. That’s interesting as well. What’s your take?

I think that was the most perceptive review that I’ve had. Though I think it’s not familiar in the Indian context but there is a kind of similar tradition in America and Britain. So the phrase ‘weird fiction’ was very good actually as that is also a bit of an influence on my writing.

The title of the book is quite positive although the story talks about the dark side of India. Tell us about the treatment of the four stories.

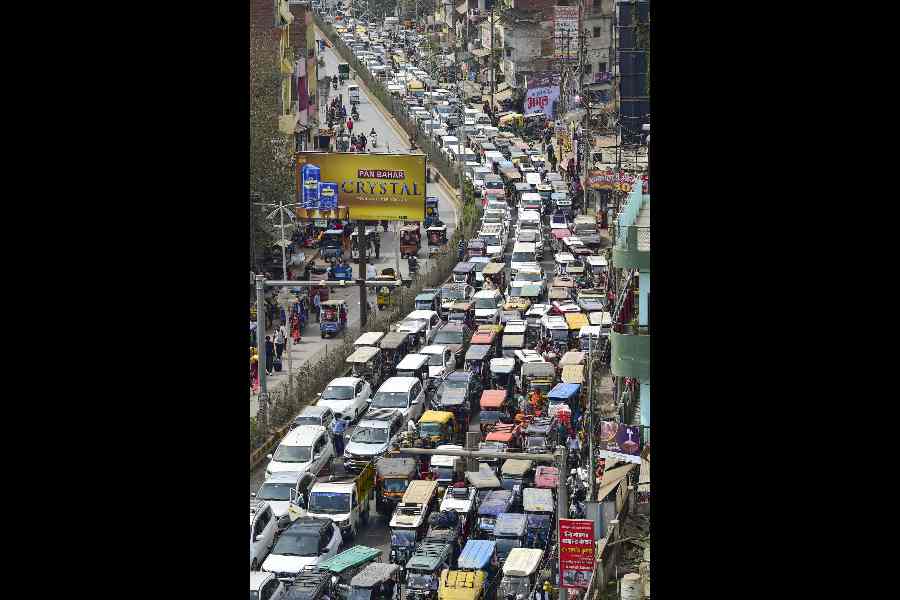

All the four moments are very dark moments. One is this sort of very similar to our present, slightly near future Delhi. I have been very open, direct and straightforward in my non-fiction works but the book is more elliptical. It’s set in this near future moment of violence against minorities, particularly Muslims. Again, the anti-Sikh riots and the Bhopal Union Carbide disaster were end-of-the-world moments. The Partition was also a kind of an end-of-the-world moment for all. These borders have been very violent to us and we are still carrying that trauma.

I think the light comes from the storytelling; the stories connect with each other. They are not just realistic accounts of the suffering but there’s an element of the uncanny, the ghost, the occult, the spiritual and the book is interested in blurring the line. The novel’s light comes from the fact that it is asking questions like what do we have in common with animals and technology? What is our relationship to AI and viruses and does it always have to be a combative relationship? Do we have to hate whatever is different? And it’s good to ask questions through stories.

So, out of the four stories, why did you want City of Brume and Bibi’s story to be the first one?

Bibi’s character is closest to my heart. Some of that comes from her being from Shillong, her struggle as an individual, somebody who has, in some sense, failed by the standards of the world as she is no longer a journalist. I am very interested in failing in my protagonist; she doesn’t fail because she is weak, in some sense, she fails by the world’s standards because she’s actually very good. She believes in love, she believes in poetry, she believes in all the good things. And sometimes my question is, does this world of ours allow people like that to flourish? Her story is the most important story of the book and I think that other novellas gain power from her story. The present of the storytelling influences the past stories in the novel.

It’s said that a writer leaves a part of them in the book or in the characters. So do we also find parts of you in the book?

Yes, probably most in Bibi, even though she’s a woman. But to me as a writer, that was an interesting challenge. I had never done a woman as a main protagonist and I said it’s about time, I want to try it. But she’s also other in other ways, and I’m not explicit about it. And then there are other characters I’m very far removed from. Like the protagonist of the Bhopal novella. It was quite disturbing when he showed up in my hand. But I said, let’s explore.

There’s also a story on Calcutta, right? Tell us about that.

That was actually the first of the novellas to be written. Set in 1947, a Partition novella, it is about a veterinary student and how his work connects him to Vedic aircraft that might stave off genocide. There’s also a slightly speculative occult and I wanted to play with it. Calcutta is my first city and it was totally different from Shillong or Assam when I came here at the age of 18, studied at the Presidency University, had my first job here before moving to Delhi and then the US. It was just filled with all these possibilities, including storytelling. With the novella, I was not writing about a contemporary Calcutta but a Calcutta I had never seen, that’s much slower, with the British still here. But, you know, it’s a bit of a love letter to the city. And it was great fun writing that part of it.

Can we expect a sequel to this book?

I am not sure at the moment but who knows?