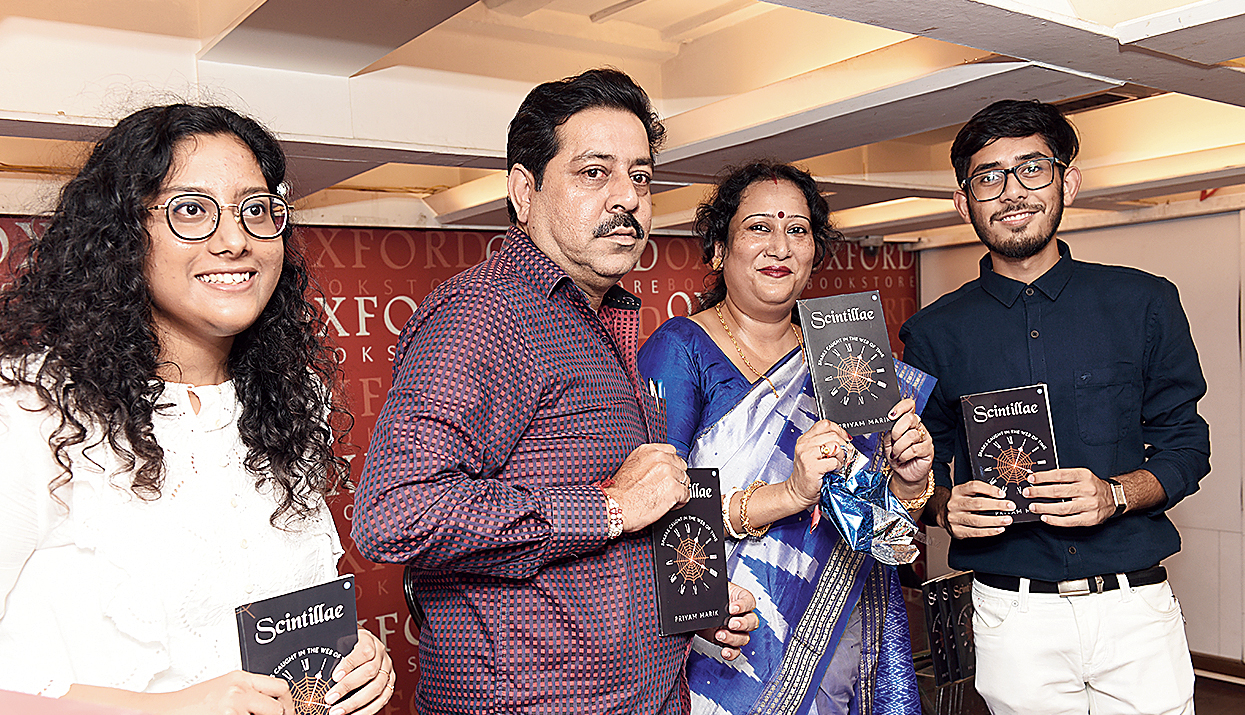

Have you even lived if you haven’t loved? As the elixir of existence, love is what animates our lives with precious pearls of magic, tempting us, teaching us, and transforming our very beings. Love is the chink in the armour of time that can reduce years to instants and eternise the ephemeral. There are, of course, different kinds of love, but following the launch of Scintillae — my first volume of poems dealing chiefly with love — my focus is on the kind that provokes delight and distress in equal measure. The kind that has been glorified from the page to the stage, but still eludes comprehension by its sincerest observers. The kind that we fall in seamlessly, but struggle to fall out of; the love that makes us feel alive, besides a whole lot else.

Can’t help falling in love

What does it mean to be in love? Is love, as Aristotle would have us believe, a union of two bodies that have merged into a single soul? I try to offer my own definition of love in the poem Stories, describing the fulfilment of love as the moment two winding stories intersect. Such a space in time can be felt, if not pinpointed.

How exactly do we fall in love? The tantalising journey from admiring someone to being immersed in their thoughts to growing accustomed to their presence at every step of the day is difficult to demarcate. I quite like how John Green puts it when he says that we fall in love “suddenly, and then all at once”. I chart a similar movement in my poem The Longest Distance, imagining love to be a string and the lovers its ends, who are pulled and stretched to their limits, before being released, to lie “torn apart, together”.

Must love remain constant like the Shakespearean love that does not “alter when it alteration finds” or can it dabble here and there, drinking from different cups to fill its insatiable vessel? Without advocating either polyamory or exclusive attention, I believe that love is about intensity, a zeal that is at once soothing and captivating — something I elaborate in The Vision.

No matter how and when we fall in love, the demons of despair are never far away, even if they visit us briefly. I am inclined to agree with Lord Alfred Tennyson that it is “better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all”, but I do not wish to gloss over the throes of love, offering instead a grim dissection of it in Goodbye.

My favourite bit about love, however, are the occasions when we feel we have transcended the boundaries of space and time. With Elvis Presley’s sonorous baritone punctuating our visceral surge towards the uncharted, we really can’t help falling in love.

Then again, for many of us, love is not about plunging ourselves into emotional tides, it is about safety and security. About companionship with our kind of person. About peaceful meals and hearty smiles, the comfort of silence. It is not the love that takes us on a swirling roller coaster of excitement, but makes us feel valued and protected in the warmth of familiar arms as we wriggle in and out of the maze of life.

Whether we idealise love (and our beloved) or prefer to stay rooted in reality, I believe that all lovers are united in their answer when the cynics, who brand love as an exercise in futility, come knocking on the door:

“After all this time?”

“Always.”

Levels of love

Koi no yokan is a delectable Japanese phrase that is used to describe the imminence of love; no, not the love-at-first-sight diet spoon-fed to us by Bollywood, but the sort of love that grows on us with a bewitching inevitability. You meet someone and the sparks fly instantly, a feeling of indescribable euphoria (the Norwegians describe it as forelsket) takes over, before love blossoms almost serendipitously. This effortless evolution of love is a theme I play with in a number of poems in my collection, especially those in free verse.

I devote a handful of verses to the lover’s classic dilemma — whether to go on or give up in the midst of unrequited love. The French give this sensation a touch of elegance through their rendition of it — la douleur exquise — though there is a subtle difference. The difference being that unlike love that finds no reciprocation, the French concept is of a love that is self-sustaining, unreturned as it may be, a solipsistic resilience that finds a sentimental resemblance in the film Ae Dil Hai Mushkil.

While writing poems about love as an abstract concept requires a very indulgent muse, I find it far easier to depict scenes in my writings, weaving the undercurrents of passion into these tentative tableaus. Intimate exchanges of love through intricate imagery, little but meaningful gestures (the pick of which, for me, is what the Portuguese call cafuné — stroking the hair of your partner), and communication without words are some of the many scenes I have tried to concretise in Scintillae. The best part about penning such poems is not the final product, but the exhilaration of imagining a scenario and slowly finding myself in it. Once I have experienced what my imagination conjures, the poetry tends to write itself. The sheet, after all, shadows the senses.

An aspect of writing that has intrigued me for a long time is dealing with pain in love. A lot of authors, especially poets, regard writing to be therapeutic, for it provides them with an untrammelled outlet for their pent-up feelings. For me, expressing my pain through the pen involves two stages — first, delving into the hurt to find a defiant energy that revolts with ink, questing for the lost in an idea best encapsulated in saudade (a mixture of strife, longing, and nostalgia); second, an artistic instinct that manipulates the individual impulse to produce something authentic, something that makes wallowing worthwhile.

When I have the poet’s cap on (usually at night), I tend to envision love as a comprehensive drama, full of protagonists and pantomimes, waiting to unravel the beauty of truth. With time, as I have moved along the levels of love (both as person and poet) — gliding on occasions and stumbling more often — I have changed my conception of this drama from stark comedy to understated tragedy. Sometimes, I have settled at calling it a mesmerising farce.

Love without labels

In the course of writing Scintillae and exploring the concept of love from a variety of angles, I have naturally been drawn to reflect on the way love is treated in today’s world. As denizens of the digital world, it has become difficult to identify genuine love from its more frivolous incarnations. In tracing this frivolity, I have come to believe that love, in the millennial age, has been taken over by labels. Today, being in love must not just be comforting, it must be cool. Healthy doses of public display of affection (or rather, affectation!), ticking off a daily checklist, burying honest responses in euphemisms, epithets, and emojis, going for Instagrammable outings, all these encompass the modern paradigm of love. While I am not accusing this love of being artificial, I feel it naively presupposes what love should be, and imposes these assumptions on the experience of love. Instead of figuring our way to the destiny that love is bound to take us in, we tend to fix a destination for love, marking its trajectory with signposts, which are often manufactured by expectation rather than emotion.

There is, of course, no right way to love, but somehow I feel that in the age of caring more about our partner’s last seen on WhatsApp than their feelings, and filling up virtual galleries at the expense of real lives, we have taken the romance out of love. By attaching distinct labels to different stages of a relationship, we have attached conditions that seldom remain uniform. Digital etiquette (if I may call it that) has turned love into an algorithm, which is still impressive and immersive, but not as intoxicating.

My first book, therefore, is also an endeavour to resuscitate, as it were, the heart of love. To generate conversation on why love is so special and why we should not relegate it to another bullet point on life’s bucket list. If, while taking a break from the deluge of social media or the still more crippling deluge of labels, you can find some solace in the picture of love upheld by my poems, I shall consider myself vindicated.

My objective is to make my readers resonate with my art, reminding them that whatever they have felt in love, they have not felt alone. And yet, for all the relatable contexts and stories you will find in Scintillae, there will be the rare poem or two that does not locate the universal amidst the personal, giving you just a glimpse into the mysteries of love I wish to keep concealed forever:

Some tales, my friend, are best untold

As lilting tunes in songs they hide,

Or shroud themselves in colours bold,

Or gently in my verse subside.