Book: An American Girl In India: Letters And Recollections 1963-64

Author: Wendy Doniger

Publisher: Speaking Tiger

Price: Rs. 699

Why do letters hold so much fascination? Is it because they are intended to communicate intimacy or, in the case of an official letter, a very specific information to a specific recipient? Why is it that when a letter becomes public, it assumes an even greater fascination? The answer, evidently, lies in its promise, in its potential of revealing something that would otherwise remain private and intangible. This is especially true when letters concern public figures, who may have written either for personal communication or, as in the case of Gandhi, for public performance. Wendy Doniger’s letters fall in between the private and the public as they sketch out her early impressions of a stay in India (1963) when she made deep friendships and honed her skills to develop and deepen her academic interest in Hinduism.

The letters that make up this book are annotated extracts from thirty-three long letters Doniger wrote to her parents while in Calcutta and in Santiniketan. As she describes them in a fine and reflective introduction, the letters are a mixed genre and inhabit an ambiguous space between diaries and letters, given the strong element of self-censure that regulated her epistolary activity. And, yet, these are refreshingly frank about personal details and impressions about India, demonstrating the enthusiasm of a young and precocious researcher who absorbed everything she encountered like a sponge and felt no inhibition in expressing her views.

Peppered with references to Hindu mythology, the facets of which young Doniger was fascinated by and compelled to show off on any and every occasion, what is especially striking about the letters is the friendships she made in India and the commentary on a young, post-colonial society facing challenges of food shortages, wars and electoral politics. Descriptions of train journeys, of public spaces like banks and post offices, the challenges of cashing an international cheque vividly bring out the India that was. Amidst this, we have incredibly sensitive impressions of social intimacy and kindness from ordinary people that are not subject to an orientalist gaze. Notwithstanding the occasional recourse to exotica, the letters bring out the pleasures of hostel life in Santiniketan in the 60s, the adda sessions in Dimock’s residence on Swinhoe street and the quiet decay that was setting into the city of Calcutta. The characters of Chanchal, the girl from Lahore, or Mishtuni Roy, who later married the free-spirited journalist, Tony Bevans, embody the complex social transformation that middle-class India experienced and gave expression to. Equally riveting are the descriptions of the seasons in Bengal: the onset of the rainy season and that of autumn, with cascades of shiuli and kaash flowers, are powerful evocations of a landscape that seems almost unreal today.

Doniger wrote the letters partly to share her experiences with her parents with whom she shared a very close relationship and partly to process the enormity of the cultural exchanges. Nothing, not even her passionate attachment to Sanskrit literature and Hindu mythology, prepared her for the experience that was India. Letters helped filter her experiences, contain her homesickness, and correct her instinctual reactions to a situation; as she writes: “It’s hard work, sometimes, being a schizophrenic on mind-heart lines; the scholar in me is having a grand time but sometimes, the little girl takes over and no amount of Mysterious East seems worth a fraction of a Late Show or a lunch at the Overseas Press Club, and then I can either force myself to work, which invariably cheers me up, or, if things are bad, I can’t work, and just go around telling myself how it is good for me to grow up a little the hard way.”

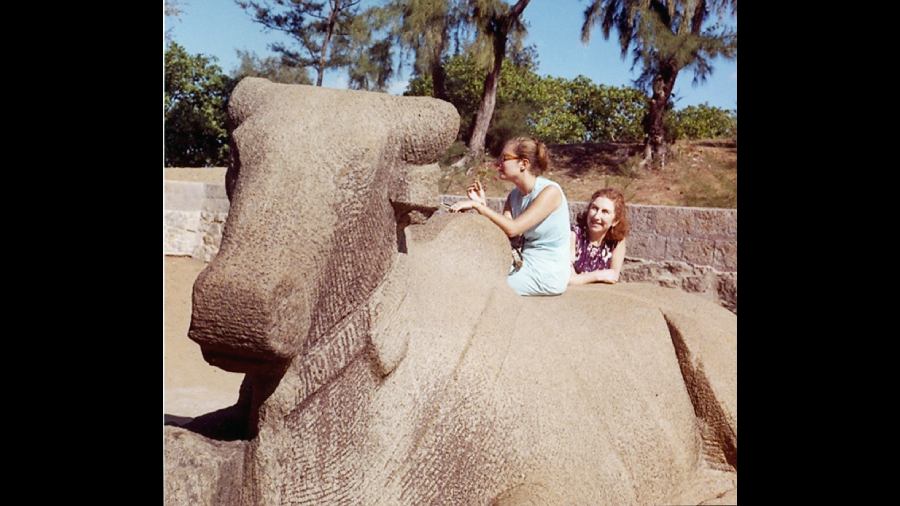

It is the collection of letters categorised under “Travels in India” that offers the reader a tangible sense of Doniger as the emerging Indology star scholar. Her descriptions of temples, of performing arts and of aesthetics and mythology at large reveal the depth of her engagement just as her sustained friendships emphasise the vitality and the fidelity of associations made in India. The trajectories of Chanchal’s and Mistuni’s lives are wonderfully etched and serve as powerful reminders of History as a lived experience. As she writes, “in my later work as a scholar, I found that I could read these two strong personalities, Mishtuni and Chanchal, into the equally strong personalities, not of the authors of my Sanskrit texts, but of fictional characters in those texts, characters who then became very real to me.”

Doniger’s letters convey strongly her passionate attachment to India, to its literary traditions and its myriad peoples whom she met and interacted with fidelity and openness. It seems strange, if not downright incongruous, that her work is treated with such suspicion and censure in the India that we live in today.