Book: The Marriage Portrait

Author: Maggie O’Farrell

Publisher: Tinder

Price: ₹799

The Marriage Portrait is an adroitly composed literary portrait of the disastrous marriage between Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, and Lucrezia de’ Medici; the same marriage that forms the subject of Robert Browning’s famous dramatic monologue, “My Last Duchess”. In the ‘Author’s note’, Farrell declares that it is Lucrezia, not Alfonso, who “is the inspiration” for her novel. In her previous novel, Hamnet, Farrell had chosen a female protagonist — Shakespeare’s wife whom Farrell refers to as Agnes Shakespeare — who has been overshadowed in the course of history by her far more famous husband. In this novel too, Farrell changes Lucrezia from the object to the subject of a narrative about her marriage.

The novel begins in 1561 when Lucrezia and Alfonso find themselves in a fortezza near Bondeno, almost alone, bereft of their usual crowd of retainers. Lucrezia has a premonition verging on certainty that her husband intends to murder her because their union a year ago has failed to produce any offspring. The narrative employs a dual time frame whereby it goes back and forth between the events in the fortezza and the time leading to that critical moment. It also charts Lucrezia’s childhood and the changes that take place in her life before and after her marriage to the Duke.

Farrell retains the devilishly debonair cast of the Duke’s character as depicted by Browning and fleshes him out to create a man of both suavity and ruthlessness. The mere hints that Browning had implanted in his poem about the Duchess’s possible nature are elaborated upon to create an untamed, rebellious, and unconventional young woman in the form of Lucrezia. Lucrezia’s mother, Eleanora, thinks of her youngest daughter as ‘difficult’, and ‘intractable’. Unlike her siblings, Lucrezia seems oblivious of her high social standing and chooses to consort with the servants. To the consternation of her family members, she is not interested in the more feminine pursuits of toilette and needlework and prefers her store of animal figurines to play with. She identifies herself not with her elder sisters but with a tigress brought by ship from the East to be kept in her father’s menagerie. Her spirit finds its true expression in her love for nature, and true to the spirit of Renaissance, in painting and the fine arts. Like her fictitious contemporary, Judith Shakespeare, Lucrezia also longs to express herself through her art. The art and culture of sixteenth-century Italian Renaissance courts with their sophistication, intrigues, and opulence are skillfully portrayed by O’Farrell.

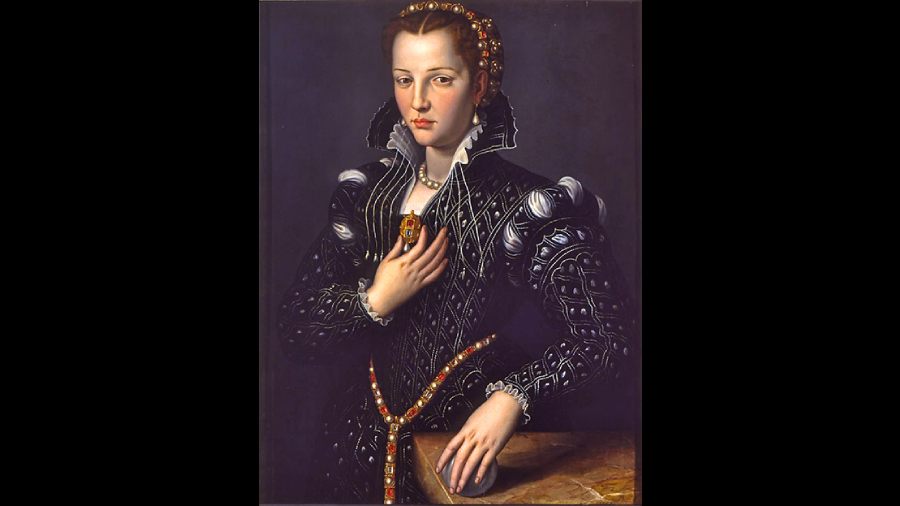

Farrell’s prose is effusive and sensuous, sometimes verging on the overly-descriptive. The use of animal imagery to underline the fact that Lucrezia is akin to a hunted animal in an oppressively patriarchal society and a political pawn in the game of dynastic marriages seems a bit laboured at times. The narrative is at its best when it depicts the marriage between the two as a not-so subtle battle of wills. On the one hand, we have the Duke’s will to confine, restrict, and tame the body and spirit of his young wife. His desire to domesticate his wife is expressed through the metaphors of restrictive dresses, confinement in rooms and, most importantly, through the marriage portrait that would preserve Lucrezia’s beauty and youth for posterity in the form of a cultural artefact. On the other hand, the continuous struggle in Lucrezia’s mind for freedom is expressed through various metaphors like unbound hair, her preference for loose garments, and her delight in roaming around the countryside. The nearly-perfect marriage between Lucrezia’s parents, Cosimo I de’ Medici and Eleanora, serves as a contrast to the one that their daughter finds herself in. Browning’s hints in his poem, sometimes even his very phrases, are inserted into the novel unobtrusively, never letting the readers forget the source text.

Whatever the shortcomings of the narrative style, they are more than outweighed by the element of suspense Farrell so competently creates regarding the Duke’s intended murder of his ‘first Duchess’. The climax of the novel, with its intriguing deviation from both history and Browning’s account of the incidents, adds a sense of novelty to the narrative. The Marriage Portrait is an engaging read and like Hamnet, or Farrell’s earlier offerings like Instructions for a Heatwave and The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox, portrays female characters with an insight and exquisiteness which are quite rare.