Rahul Bajaj, one of the giants of Indian industry, died last month. He spent his life building Bajaj Auto into a global giant. During the 1960s and the 1970s demand almost always exceeded supply but Bajaj always took care to ensure a quality product. When Bajaj separated from its Italian partner Piaggio it had to slowly build its own research team in an era when India’s knowhow was still very limited. Here's the story of how the research team took its early tentative steps:

After Piaggio’s formal departure on 1 April 1971, the Vespa was simply re-badged as ‘Bajaj’. They had the machinery Piaggio left behind, but no longer could Bajaj depend on a partner for technology.

‘By the early 1970s, the black chapter for Indian industry had begun,’ explains Bajaj, ‘and according to me, was the worst in the history of independent India. Where did an Escort scooter go? Nowhere. The two-wheeler division got sold to Yamaha. Jawa, I don’t even know where the company is now. During that decade, hardly any new technology agreements were signed in the private sector, especially in the auto industry and the engineering industry. That’s why we started a research and development (R&D) department in the early 1970s.’ A small but enthusiastic workshop emerged. The Bajaj Chetak scooter appeared on roads in 1972.

A three-wheeler goods carrier had been in the making under the Piaggio oversight. The energized R&D team reshaped the design such that it could be marketed as an autorickshaw, a pickup or a delivery van. ‘This model was aimed for exports as well as the home market,’ evokes Bajaj. ‘I wanted to smother competition, and I had three key priorities—improve the fuel efficiency of existing products, develop new products for niche markets, and come up with a fundamentally new three-wheeler design.’

In mid-1973, the team showed Bajaj autorickshaw prototypes with seating capacities of three and four passengers. Test marketing went well. Now it was up to the management to secure approvals for plying them as taxi-cabs from road transport authorities in the states.

The next year, the building, now officially dubbed the ‘Engineering Centre’, saw the team develop a three-wheeler with a trailer and payload capacity of 715 kg. An earlier version of a pick-up van got a rear flap and a stronger chassis. The three-wheelers now came garnished with trafficator lights and an electric windscreen wiper. Fuel economy, substituting imported parts in favour of local materials, redesigning the braking system, suspension plates, brake drums, reverse gear systems, satellite gear housing for maximum efficiency and economy were the names of the game.

With pretty much the same Akurdi (where Bajaj Auto’s first manufacturing plant was located) team running Maharashtra Scooters, Priya, a motorized and geared scooter assembled at the Maharashtra Scooters Satara plant from Akurdi CKD packs popped up in showrooms in 1976. In the same year, Akurdi introduced the Bajaj Super, a two-stroke 150 cc scooter, which looked remarkably like the Vespa Super. Both had 8-inch wheels and a powerful headlight. The Bajaj Auto models continued to have a Vespa-like air.

The core problem of scooter parts remained until the late 1970s: Bajaj Auto didn’t have the know-why and the know-how to make critical components and remained dependent on Piaggio imports. A two-pronged strategy developed: royalties and imports of components from Piaggio to be set off by funding from the World Bank. Though this strategy played out for some years, Bajaj recognized that this approach could not be more than a temporary relief. A strong export thrust to raise funds for imports became the mantra.

The R&D unit began to show promise when a rear engine autorickshaw, the RE, appeared in 1977, but the team’s biggest achievement in 1979 was probably the successful modification of the Bajaj-Chetak scooter to conform to US Federal Motor Vehicle Safety standards during the legal court case battle with Piaggio in the US. The kudos began flowing in.

Skills improved in the 1980s as the R&D team learnt the ropes. ‘Internally, in the mid-1980s, many changes were taking place inside Bajaj Auto,’ describes Bajaj. The promise he sensed in the R&D team led Bajaj to make an unusual gesture: he situated an engineering research centre in a separate building of its own, including independent paint and assembly facilities.

Bajaj congregated a small ecosystem of knowledge providers. There were three from Italy—Vigel SpA for technical know-how and assistance for the manufacture of special purpose machine tools for captive consumption; IdeA for restyling of the rear engine three-wheeler body; and Industria Prototipi and Serie to create a body design for a new Bajaj scooter. From Spain, Bajaj invited Moto Piatt S.A. for electronic components like magnetos and electronic ignition system; from Australia, the Sarich Orbital Engine Company to develop a fuel injection system for 150 cc scooters to reduce fuel consumption and emissions; and AVL of Austria for engine development.

The pool of specialists expanded in the 1990s and extended to include the Japanese. A technical agreement was struck with Japan’s Kubota Corporation in 1995 to source technology for a 417 cc four-stroke diesel engine for three-wheelers. Tokyo Research and Development Centre, a team of former Honda Motor specialists, worked on a scooter prototype from external design and styling to the engine. Americans and Italians continued to work alongside. The mandate to US’s Unique Mobility, Inc. was to develop an electric power autorickshaw, as also a prototype electric and hybrid-electric system, and Cagiva, an Italian firm, for the high-end Cagiva CRX, a 150 cc four-stroke scooter.

The in-house R&D team slogged to develop a 100-cc scooter marketed under the brand name Bajaj Cub. A limited-edition release with an electronic ignition system, the Bajaj Cub was released in 1984 and was rather quickly discontinued. Local R&D had some way to go.

Expectations ran high also for the M50. A moped at heart, the M50 was not a regular motorcycle with a petrol tank in the middle. Mirroring Japanese technology in its packaging, the M50 differed only in its scooter-type handlebar-mounted gear shifter. As many as 1.1 million bookings poured in. The orders vanished into thin air just as quickly. Mismatched components affected driveability, fuel efficiency and reliability. Bajaj immediately set up a special task force. R&D suggested a bigger 80 cc engine. The M50 was converted to the acceptable M-80. ‘The first day of booking for the Bajaj M-80 was memorable,’ remembers Bajaj, ‘in the city of Udaipur, there were such lines, with mounted police to keep order.’

A motorcycle, the Kawasaki Bajaj (KB) 100, was born in Waluj in the same year as the Bajaj M-80 was born in Akurdi. The modest success with in-house developed products led to higher confidence in core R&D capabilities. Nevertheless, Bajaj continued to allocate a relatively low amount on R&D as percentage of sales as compared to the amount spent by the global automobile majors stalking his territory.

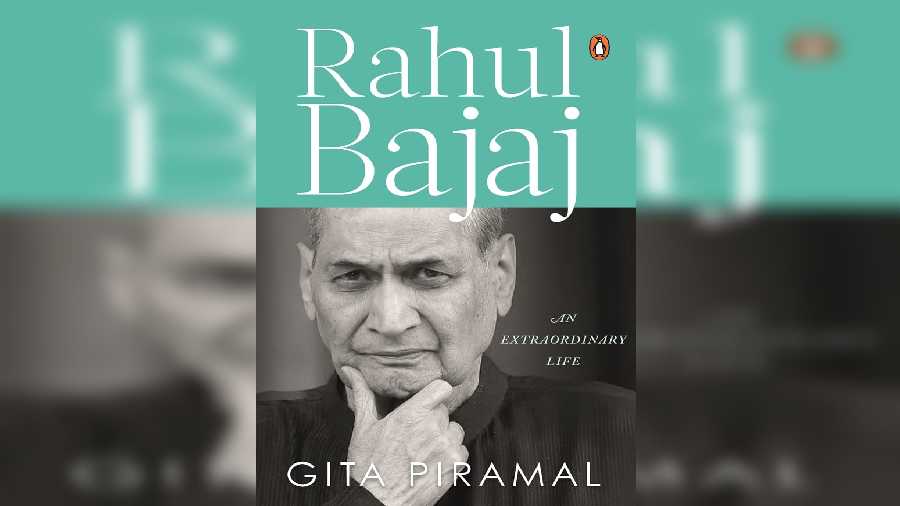

Extracted from Rahul Bajaj: An Extraordinary Life by Gita Piramal

Price: Rs 799

With permission from Penguin Random House