Book: Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann, Pantheon, Rs 2,075

Author: Daniel Kehlmann

Publisher: Pantheon

Price: Rs 2,075

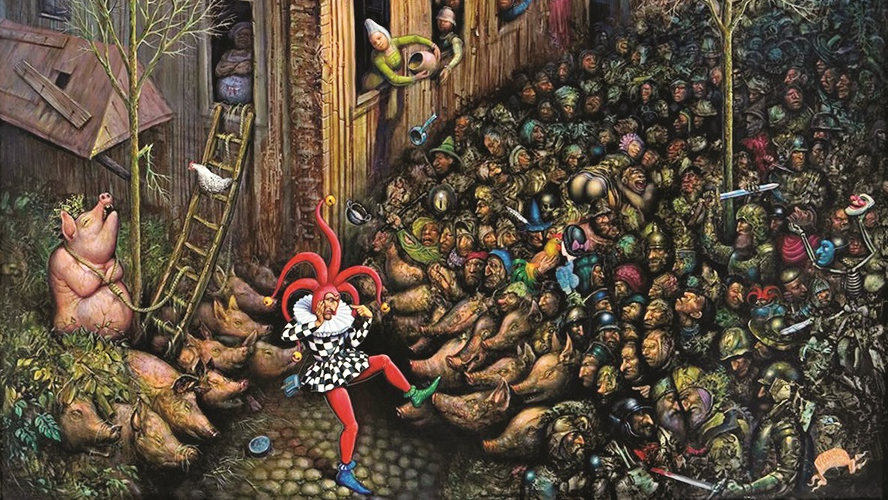

Tyll, Daniel Kehlmann’s biographical novel on Tyll Eulenspiegel, the picaresque German trickster hero, is a rich retelling of the stories that have come down to us from medieval chapbooks and nineteenth-century reconstructions that connected the protagonist to the Reformation. Of course, Richard Strauss’s unforgettable tone poems probably introduced Tyll to classical music aficionados. For those who are not familiar with Tyll Eulenspiegel (his last name means ‘owl mirror’), he is a figure from German legend who is famous for his tricks, witty jests and practical jokes that border on the scatological even. As the entry on Tyll in the Encyclopaedia Britannica explains: “The earliest extant text is Ein kurtzweilig Lesen von Dyl Vlenspiegel (Antwerp, 1515; ‘An Amusing Book About Till Eulenspiegel’); the sole surviving copy is in the British Library, London. The jests and practical jokes, which generally depend on a pun, are broadly farcical, often brutal, sometimes obscene; but they have a serious theme. In the figure of Eulenspiegel, the individual gets back at society; the stupid yet cunning peasant demonstrates his superiority to the narrow, dishonest, condescending townsman, as well as to the clergy and nobility.”

As a collection of multiple stories without any fixed plot, Tyll could probably be best described as a picaresque novel in the tradition of Lazarillo de Tormes or the novels by Henry Fielding and Laurence Sterne, where the protagonist is a commoner who lives by his wits and cunning in a world dominated by the aristocracy, gentry and clergy.

Any book based on the legendary German trickster-figure is likely to be intriguing because of the subject alone. Kehlmann begins his novel by giving Tyll a tragic but intriguing origin story that reads as if it is straight out of Montaillou: Cathars and Catholics in a French Village 1294-1324 by the Annales historian, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, where the life of an obscure village in post-Reformation Germany is laid out in all vividness and quite like the Inquisition in Montaillou, the Jesuit fathers arrive in Tyll’s village and decide that his father, the autodidact miller who possesses a Latin book that he cannot read, should be burned at the stake as the minion of Satan. At the same time, the quotidian lives of the villagers go on uninterrupted — the cows start lowing because they haven’t been milked on the day of the execution, even as the learned Jesuit fathers conduct the trial of Claus Eulenspiegel, the miller.

Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann, Pantheon, Rs 2,075 Amazon

The later sections of the novel, however, struggle to hold the reader’s interest and after being totally absorbed in the tale of Tyll’s village, the reader is likely to feel lost in the many courtrooms, battlefields and the variety of landscapes that appear one after another. One would agree with Anthony Cummins who notes in his review of the book that it is “an episodic hopscotch through the royal politicking behind the continent-wide bloodshed” where the story of the protagonist is often relegated to a secondary position. We see Tyll as a juggler and a man of wit but short of some randomly portrayed acts of legerdemain or a couple of scenes where the protagonist’s presence of mind is noted or his fame is discussed in public (the Kaiser himself wants Tyll in his retinue), there is little to testify to his legendary reputation. Tyll’s story is entwined with that of many other characters, some of them real historical personages such as Elizabeth, the daughter of James I of England and the wife of the Elector of Bohemia, and scholars like Athanasius Kircher. In the eclectic mix of the fictional and the historical, many names that appear in the later sections of the novel will often send the reader off to look them up in history books and encyclopaedias, sometimes even increasing the confusion further as many of them are very convincing and realistic creations by the author.

Kehlmann introduces an interesting mix of literary devices and tries to retell the history of Germany, Bohemia, the Low Countries and Continental Europe by extension through personal vignettes of multiple characters drawn from different walks of life. Tyll usually turns up in all of these narratives, although mostly in a less important role. One element that held out much promise in the initial sections was the hint of magic realism: the talking donkey that belongs to Tyll, however, does not get much focus in the novel unlike its garrulous counterpart in the Shrek movies. Kehlmann is, of course, a master of his craft and the vignettes themselves are very immersive and create the sense of atmosphere wherein the devastation of battlefields, the intrigues of courtrooms and the curiosity-filled chambers of the polymath, Kircher, all come to life. The character of Tyll Eulenspiegel also does not fail to impress wherever he appears in the book. Despite showing much promise, Kehlmann’s Tyll, nevertheless, has room for improvement. Although the picaresque genre that the novel adopts is all about creating a multiplicity of stories, some coherence and a better interweaving of the tales would have gone a long way in giving the reader some direction.

Of course, it is also possible to read this lack of coherence as a deliberate strategy used by the author. Knowing the stories that surround the elusive Tyll Eulenspiegel, it is possible that Kehlmann’s denial of narrative coherence is deliberate and in keeping with poststructuralist positions on narration, it questions the reliability of the narrative especially when it is about the quintessential trickster figure so renowned for his sleight of hand. After many adventures in the novel, whether involving the protagonist or not, when one reaches the last pages, it is only natural to wonder whether the novel has really ended. Just as Tyll’s father ponders questions such “What is time? Does Hell exist? What are stars, and how many are there?” one might be tempted to ask whether Tyll is real or whether this is all magic. At the end of the novel, Elizabeth the Winter Queen asks Tyll if he would not prefer to go with her to England and die in a warm bed; he responds that it would be better not to die at all. For centuries, Tyll has remained immortal through his many shapeshifting tales, and Kehlmann’s novel carries on the tradition.