Book: The Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead Philosophers

Author: Eric Weiner

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Price: Rs 699

Eric Weiner is a man of many parts. He is an award-winning journalist, a columnist, a popular speaker and a traveller. Above all, Weiner is a seeker. His lived experiences moulded his thoughts and shaped his identity. From India, he learnt the secret of harmony in chaos; Israel instilled in him the importance of savlanut (patience); Japan taught him the art of being silent as well as the beauty in small things.

It was this seeker’s quest to know more about the world’s unexpected and unlikely happy places that resulted in Weiner’s first book, The Geography of Bliss. His second book, Man Seeks God, is a record of his “Flirtations with the Divine” as is suggested by the book’s subtitle. The Socrates Express is Weiner’s fourth book. Here, he is “In Search of Life Lessons from Dead Philosophers” as is affirmed by the subtitle. For Weiner, places are “repositories of ideas”. Places matter. That is why he travels. He believes in the importance of ‘meeting’ dead philosophers on their own turf — reading their writings where the thoughts originated — and in self-dissection. In Athens, Weiner finds himself in a café sipping Mythos beer, reading Epicurus’s three types of desires, following which he questions his own obsession with bags — “fifty-four bags of various vintages and leather-and-canvas configurations”. Would Epicurus categorize his desire for bags as “natural and necessary”, “natural but not necessary”, or “neither natural nor necessary”?

The book imparts a three-pronged knowledge on philosophy and philosophers. First, there are the life lessons, one each from carefully-chosen philosophers, answering a specific ‘How to...’ question. These philosophers are both women and men, from different spaces and times, and with different philosophies. Women philosophers are rarely heard of in the world of philosophy: to Weiner’s credit, he travels to Kyoto to meet Sei Shonagon, he meets Simone Weil in Ashford; in Paris, he converses with Simone de Beauvoir.

Second, The Socrates Express shows that there are common threads among philosophers, either in their philosophy or in their mannerisms. Thus, like Epicurus, Shonagon, too, developed a categorization of pleasure. Confucius and Socrates taught in an informal and conversational style. Socrates, Rousseau, Thoreau, Nietzsche, and Gandhi loved walking. Marcus Aurelius and Thoreau were “wisdom scavenger[s]”. Socrates and Thoreau annoyed people with their impertinent questions, but they were also good listeners and practised rigorous self-introspection.

Third, there is Weiner’s tendency of associative reading of the philosophers he is journeying with. Each of these 14 philosophers converse with him in some manner or the other, some more intensely than others. By the end of the journey, we have a portrait of the author, his habits, his likes, and dislikes.

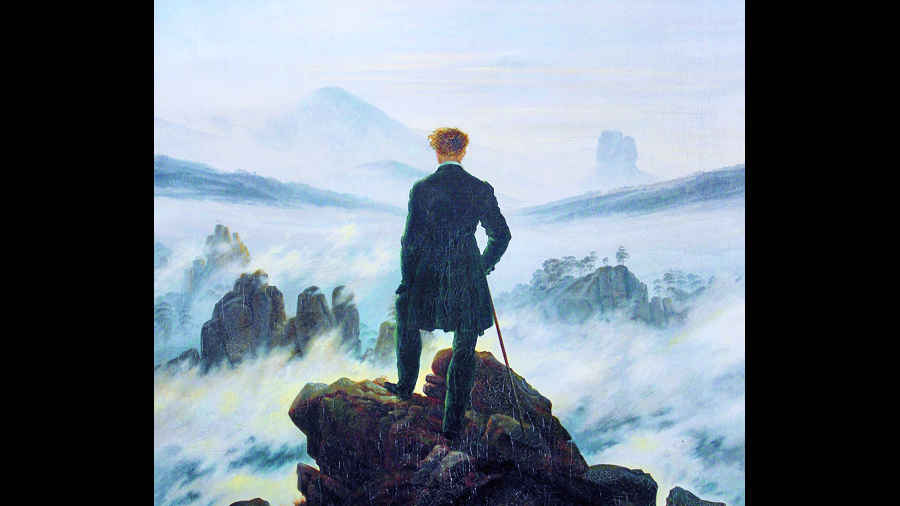

The Socrates Express is written in the form of a day’s journey. Between the “Departure” and “Arrival” are three periods, Dawn, Noon, and Dusk, during which Weiner converses with his chosen philosophers. Dawn breaks with Marcus Aurelius and the “Great Bed Question”: to rise or not to rise from bed. This frivolous question is linked with honouring one’s duties and dealing with difficult people. With Socrates — the great questioner — Weiner walks the path of crazy wisdom, “casting aside social norms and risking ostracism, or worse, to jolt others into understanding”. The next companion is Rousseau — the solitary walker — who walked to think and thought on the art of mindful walking. From Thoreau, he learns to see with the heart, to look at the world from unusual angles even if it means bending over and peering through one’s legs. Schopenhauer summons him to listen to others and to himself mindfully.

At noon, Epicurus explains the value of sensual knowledge and the meaning of true pleasure. Simone Weil shares the wisdom of attentive and receptive waiting, which involves self-discipline and deep empathy. The “spiritually omnivorous” M.K. Gandhi enlightens Weiner on fighting: under certain circumstances, fighting is a sacred duty and a necessary good. Confucius speaks of the benefits of practising ren (benevolence). At noon end, Shonagon shows him how to appreciate the small and simplest things in life.

The Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead Philosophers by Eric Weiner, Simon & Schuster, Rs 699 Amazon

As dusk falls, Weiner learns from Nietzsche the secret of eternal recurrence; that reaping the best fruitfulness from existence is possible by living dangerously and with no regrets. Epictetus teaches him how to cope with the angst of the unknown and the unpredictable. From Simone de Beauvoir, who feared ageing more than death, Weiner understands that old age collides with humans, and one is never ever prepared. Finally, Montaigne whispers to him about the art of dying fearlessly.

The journey transforms Weiner. At the arrival point, he is confronted with a broken smartphone. An agitated Weiner wonders what good has come of spending years assimilating the thoughts of great philosophers if their philosophy could not help him circumvent a mini-crisis. That is when he pauses, revisits their thoughts, and understands that he will live with obstacles and learn to navigate them, da capo, again and again.

Weiner admits that he is a student of human quirks. He amasses interesting tidbits on the philosophers he is journeying with, presenting them as human beings, not just repositories of lofty ideas. We learn of their sleeping and waking habits and rituals. Marcus Aurelius is not a morning person; Simone de Beauvoir woke up at 10 am and dallied over her espresso; Kant was up at 5 am, had a cup of weak tea, smoked a pipe and then worked; Nietzsche woke up at dawn, splashing cold water on his face, drank a glass of warm milk, and worked till 11 am.

The Socrates Express stays true to its title, employing expressions — “train of thought”, “of the railroad age” — related to the railways. It presents facts and technical data and we also learn that not all trains are the same. Some sway gently, while some shake and rattle. The trains are also anthropomorphic. They “make human noises”; “snort”, “whistle”, “belch”; railway cars “whine”, “squeak”, “protest”. The Japanese shinkansen, with its “flat platypus nose attached to a toned swimmer’s body”, is both ridiculous and beautiful. Weiner also cross-checks his assumptions and corrects erroneous ideas. In one of the endnotes, he clarifies that the expression, ‘off the rails’, is not the fruit of the age of the railroad; the philosopher, Thomas Hobbes, coined the term more than a century before the first railroad. Each philosopher with whom Weiner travels has been given useful explanatory endnotes. There is also an interesting bibliography and references for further reading on the philosophers discussed as well as on philosophy and train travel. All these make The Socrates Express a worthy read.

However, one cannot overlook the fact that the plot does not throw up surprises. Like his earlier works, this one is replete with scatological humour. Is it acceptable to swear and use obscene expressions in one’s writing? Weiner’s use of such language points to the need for a philosophical engagement on the semantics of profanity. Right at the beginning, Weiner notes, “Wisdom is something you do”. He speaks of wisdom as a skill that one can learn through dogged effort. But is wisdom only action? Or even just a skill, an art that can be learnt and honed? Wisdom, admittedly, is manifested in action, but is it not more than action or an expertise? Is there not the intuitive wisdom, of the kind experienced by Elijah at Mount Horeb

Weiner is mistaken in noting that the last journey of Gandhi was 13 days after his assassination when his ashes travelled on a train from Delhi to Allahabad to be immersed at the Sangam. Records show that there were at least three other journeys. One involved train travel when, on January 29, 1997, part of Gandhi’s ashes travelled in a second-class coach of the Puri-New Delhi Purshottam Express to be immersed at the Sangam.

Weiner has an all-consuming hunger that refuses to be sated with religion or travel. This hunger is his love for wisdom. He is quick to point out that what philosophy and philosophers do is to look at the world differently. What matters is not possessing wisdom, but its pursuit. As for philosophers, they trouble us. They nag; they question assumptions, especially their own.

This book could be a great companion during the pandemic, walking us through 14 stations of philosophical therapy: how to wake up; how to wonder; how to walk and walk the talk; how to see with other eyes; how to listen with more than one’s ears; how to relish the transient and the abiding; how to heed; how to fight the good fight; how to be kind; how to appreciate small and great things; how to live life with no regrets; how to cope; how to grow old; how to take leave of this life.

The Socrates Express is all this and more. It teaches us that the journey’s end does not matter as much as the peregrination itself. If this is not the beginning of wisdom, then what is?