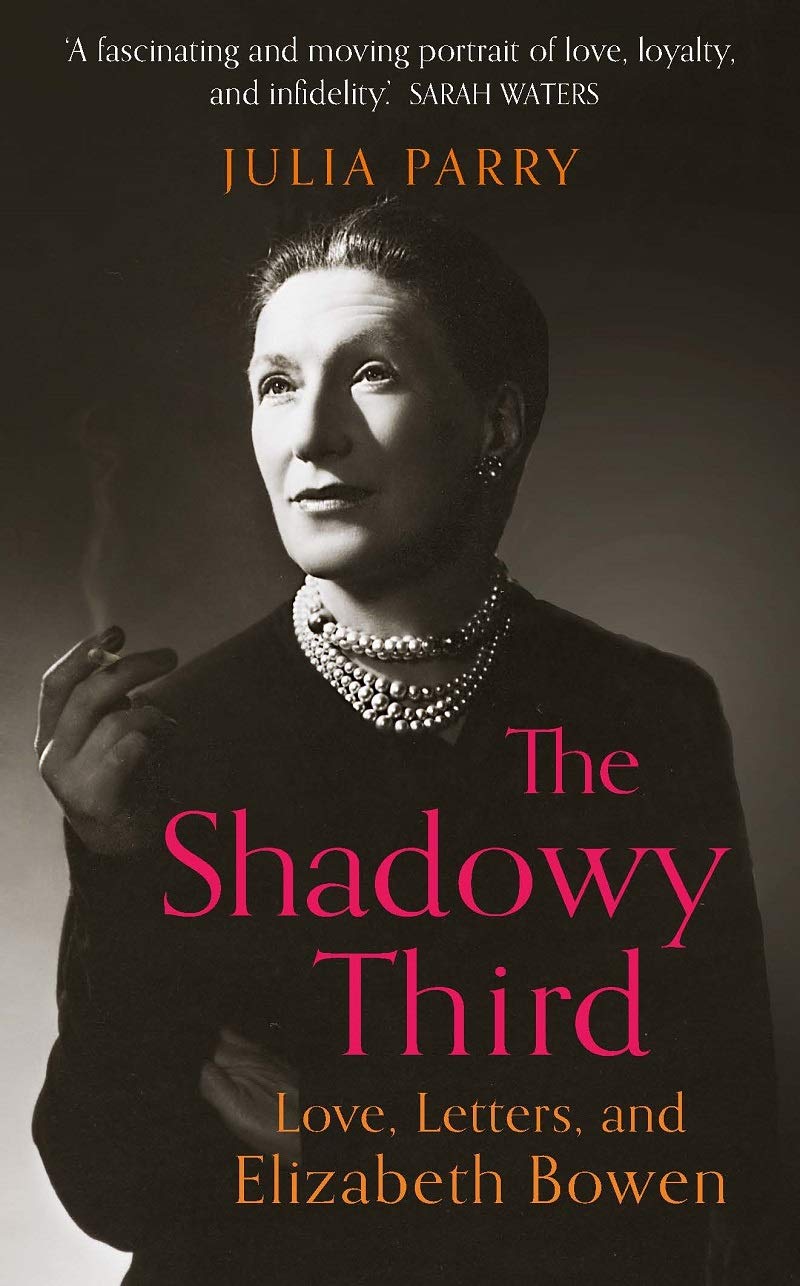

Book: The Shadowy Third: Love, Letters, and Elizabeth Bowen

Author: Julia Parry

Publisher: Duckworth

Price: Rs 1,780

“Elizabeth Bowen is a writer obsessed with letters. Her belief that a letter could establish a psychic affinity between sender and recipient is everywhere in her fiction.” Thus begins Julia Parry’s The Shadowy Third: Love, Letters, and Elizabeth Bowen, an epistolary biography as well as a story of Anglophone literature as it was written, read and critiqued between the 1920s and the 1940s in Britain and in its colony — Calcutta.

It is also a deeply personal memoir of a granddaughter delving into her grandma’s repository of letters and using those missives — lenses — to review the fraught relations among a modernist author, Elizabeth Bowen, a modernist critic of English literature, Humphrey House, and his wife, Madeline Church.

Parry is a principal actor in her own narrative, not merely because she is the granddaughter of Madeline, or because she recognizes the importance of these letters and lays claim on them as more than narrowly familial, but because she reconstructs a cultural past, reanimates it by breathing life into those missives, revisits and re-imagines those space-events for the contemporary readers.

It is difficult to decide, even after going through the narrative, as to who the shadowy third could be in this triangular relationship. Is it the shadowy Madeline, the forbearing wife in a triangular relationship, but emerging with the courage and conviction to bring her deceased husband’s scholarly endeavours out of the shadows to their appointed end? Or is it Elizabeth Bowen, the Anglo-Irish auteur, who is creatively sustained through a symbiotic relationship with her lover, acolyte and critic, Humphrey House? Or is it House himself, torn between two strong women, and hiding behind the shadowy persona of that non-intrusive critic of English literature? Or is it the frigid wife, Naomi, portrayed as a character, an uncanny presence in Bowen’s novel, The House in Paris?

The Shadowy Third: Love, Letters, and Elizabeth Bowen by Julia Parry, Duckworth, Rs 1,780 Amazon

Parry’s revisiting of all those places — Oxford, London, Dublin and County Cork in Ireland, Cambridge, Calcutta — where the trio had met, mingled and dispersed, after the passing of years, textures the narrative and renders it delectable, especially to the breed of Anglophiles that still resides in and between these places. It is a story of houses, colleges, cities, and letters that bind and separate. The book’s photographs accentuate the readers’ delight, as there is a ‘before’ and ‘after’ quality about most of them. Some ‘after’ pictures bear traces of time’s ravages, some of World War II bombings, some of structural transformations, such as the metamorphosis of the great Presidency College of Calcutta into a university.

In the final count, this is an incestuous book, exploring those private pleasures and pains of that endogamous group comprising teachers, students, scholars — aficionados of that strange beast called ‘English literature studies’. It revisits all those shrines where such studies were sacralized: the university colleges of Oxford (especially Wadham), Exeter, Cambridge and Presidency College. It is about those god’s and goddesses that trod these paths — artist-intellectuals, such auteurs as Virginia Woolf, Isaiah Berlin, Maurice Bowra and, of course, Elizabeth Bowen. T.S. Eliot and Gerard Manley Hopkins dominate this ‘inscape’ as House was to memorialize Hopkins in a ‘life narrative’. Bowen’s radio plays on Jane Austen are significant as Bowen, like Austen, was obsessed with marital relationships. There are other shrines such as Ripon College (now Surendranath College), Coffee House and the Das Gupta book store on College Street. Readers would also discover teachers, such as Sajni Mukherji (Kripalani), in this narrative: Julia visited them in her odyssey to retrace the peregrinations of her grandmother and grandfather.

Parry evoking Calcutta’s Victorianists is due to Humphrey House being a foundational figure and his teaching in Presidency and Ripon College. His monumental critical work, The Dickens World, dominates this book, as does Parry’s discovery of its mangled copy in the Presidency College library. What also dominates the narrative is Madeline’s ability to complete her husband’s project of compiling, editing, annotating Charles Dickens’s letters in a multi-volume set. Although Humphrey did not live to see this archival work, it has and will remain his and Madeline’s lasting contribution to studies on Dickens and his contemporary Victorians.

This book might just inspire us to revisit Elizabeth Bowen’s narratives, Humphrey House’s critical works, and the dying art of letter-writing that bound them together.