Book: The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War

Author: Louis Menand,

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Price: $35

“This book is about a time when the United States was actively engaged with the rest of the world...

Ideas mattered. Painting mattered. Movies mattered. Poetry mattered. The way people judged and interpreted paintings, movies, and poems mattered.” (Preface, xi-xii)

When was this time, when America reached out generously to worlds and peoples outside of it, and was so flooded with ideas and thoughts and art and culture that it was spilling out and over and all about? And why should it ‘matter’?

Louis Menand, professor of English at Harvard University and Pulitzer prize-winning author of The Metaphysical Club, has produced another tour de force in this expansive and erudite, thoughtful, provocative and rollicking exploration that is The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War. Careening through two decades of a cultural and intellectual high in the United States of America — between the end of the Second World War in the mid-1940s and the start of the Vietnam War — it feels as if Menand is, in his narrative, mimicking the spirit and speed of the times he captures, now that they have vanished into a very dim past. And the vehicle he chooses for telling his tale is as compelling as it is surprising: stories of a host of its most colourful, memorable characters, stars in their own right, whatever the medium they worked to perfection through their illustrious lives.

In Menand’s account, the Second World War left America in a state of great material advantage but not its equivalence in arts and ideas; he narrates how, in the course of the following twenty years in the middle of the 20th century, the country leapfrogged ahead in the many games of culture and intellect. The US then transformed into a nation that produced impressive numbers of artists, writers, film-makers, actors, musicians, thinkers and critics, for the first (and perhaps last) time, and until their creative and all other fortunes began to tremble and shake with the debacle in Vietnam, they appeared to ride the wind and inscribe their names across the sky in blazing letters.

The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War by Louis Menand, Straus and Giroux, $35 Amazon

How was this glory birthed? Menand is pragmatic, if not disillusioned. It was neither by sheer talent nor inordinate luck; they owed much of their spectacular fame and triumph in the worlds of art to American wealth and American aggression in the wake of the Second World War when Europe was flagging. So this curious tale of the rise and rise of American culture for a glorious twenty-year run is not at all unaccounted for but, in fact, continually grounded by sharp and serious readings of how modern American finance, technology, politics and social myth-making shaped so much of its success. The everyday lives of its star performers in all spheres of the arts, however, were full of laughter and sorrow and fame and shame, as is wont — and those are the tales that Menand captures with flourish and charm and a palpable sense of esprit de corps, so that the nearly 730 pages of text and 100 pages of detailed notes do not weigh heavy on the mind, as the hardbound tome does in the hand.

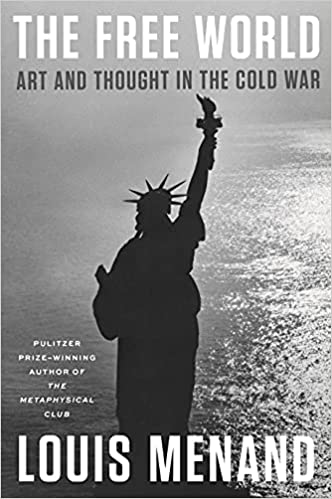

In fact, the cover of The Free World does not announce or endorse any sense of glory: in sombre blacks, whites and greys, it presents the Statue of Liberty from the back, in a dark silhouette, brooding upon a grave and silvery sea. There are, possibly, at least two significances to this image and imaging: ‘Freedom’, or what the statue embodies, is central to the America that Menand is holding up as exemplary, but the evening pall that has fallen on the Lady of Liberty is one of regret, of splendours impermanent. The shadow of a reality check pervades this scrupulous study of artistic brilliance and toil — woven through the stories of larger-than-life personalities who strode the world’s cultural stage like a colossus — inserting caution and doubt and scepticism: not bringing the statue down, but continually, meticulously, exposing its feet of clay. Menand writes, “Now I can see that freedom was the slogan of the times... As I got older, I started to wonder just what freedom is, or what it can realistically mean.” He undertakes this mammoth task, it seems, to both chronicle what that freedom brought then, and to sound a note of dull disappointment about what it realistically meant.

And so The Free World runs a marathon across America lasting two decades, its chapters stopping by personality-signposts among its greatest in ‘art and thought’: George Kennan, George Orwell, Jean-Paul Sartre, Hannah Arendt, Jackson Pollock, Lionel Trilling, Allen Ginsberg, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage, Elvis and the Beatles, Isaiah Berlin, James Baldwin, Jack Kerouac, Andy Warhol, Susan Sontag, and Pauline Kael. Many more are lightly touched. Menand fleshes out biographies with twists; telling memorable tales, throwing kaleidoscopic light upon the wonder-years in art and culture and critical thinking of mid-20th century America, its darker underbelly always and firmly within vision. He has, I believe, pulled off the coup that his artists and thinkers could not possibly preserve unstained.