Book: The Estate of Major General Claude Martin At Lucknow: An Indian Inventory

Editors: Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Publisher: Cambridge Scholars

Price: £64.99

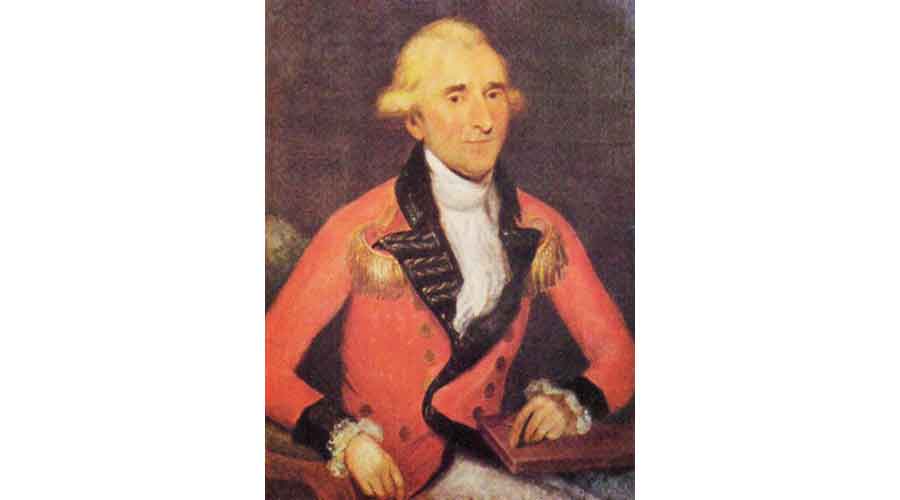

If style is the man himself, so are his possessions. The fascinating book under review presents, for the first time, an inventory of three houses of Claude Martin (1735-1800) through commentaries by six experts along with a catalogue of books in his library. Rosie Llewellyn-Jones says: “Inventories are the poor relations of historical research.” Yet, they provide an insight into the mind of this handsome Frenchman — soldier, entrepreneur, gunmaker, architect, surveyor and polymath with an amazing variety of interests. Expert commentaries throw light on the material culture of the times, an adventurous nabob’s sybaritic lifestyle and so on. The book reveals a recherché world of luxury and leisure where firearms were as exquisitely crafted as jewellery and the colours of fabrics had such poetic names as “‘amooah’ (a shade of green like an unripe mango)” — a world mirrored in the works of European masters like William Hodges and Johann Zoffany who visited India and painted canvases that often featured Martin and were part of his art collection, which “has almost completely disappeared from studies”.

Claude Martin is remembered for the schools he founded posthumously in Calcutta, Lucknow and Lyons, his hometown in France. A product of the Enlightenment, he excelled in mathematics and physics, which is reflected in his prodigious collection of books on natural science. He signed up with the French Compagnie des Indes Orientales in 1751, but had no qualms about switching loyalties and joining the East India Company in 1763 when the French lost Pondicherry. He rose to become a Major General and gave up all plans of returning to France after the “Reign of Terror” during the 1788 Revolution. He lived in Lucknow from 1766 till his death, and cleverly acquired the lucrative position of superintendent of the Lucknow arsenal of the Nawab of Awadh, Asaf-ud-Daula.

The Estate of Major General Claude Martin At Lucknow: An Indian Inventory edited by Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, Cambridge Scholars, £64.99 Amazon

Llewellyn-Jones writes in the Introduction that of the three properties to be inventoried, Château de Lyon and Constantia were in Lucknow, and Najafgarh near Kanpur (he had properties in Calcutta and Chandernagore as well); the third is in ruins. The “perfect museum”-like Château, where the childless Martin died on September 13 surrounded by treasures, had a steam engine building near the main building and a separate zenana for his seven mistresses. The Nawab of Awadh, Saadat Ali Khan, insisted on acquiring it two years after Martin’s death. The larger “palace”, Constantia, was unfinished when Martin died but his library of about 4,000 books (La Foutro-Manie, poeme lubrique number 544 in the catalogue was the sole smutty title) had probably been shifted into it. “No other inventory in the East India Company Records matches that of Major General Claude Martin either in length or in the sheer variety of household possessions,” she writes.

Martin’s “Last Will and Testament” was published in Lyon three years after his death, but the detailed inventory was discovered in the British Museum (which then housed the present British Library) in 1975. The Calcutta auctions of his property began on January 1, 1801, and Joseph Quieros, Martin’s executor and adjutant, and Zulphikar (James) Martin, the adopted son of Boulone Lise, Martin’s favourite mistress, made all the arrangements double quick.

Martin lived large. Whenever he placed extravagant orders for firearms, fine carriages, silver, statuary, art, timepieces and scientific instruments with leading manufacturers or craftsmen of Europe or the UK, he spared no expense, even at considerable risk of the objects not arriving undamaged and uncertainty about the time taken to deliver them. Unlike the gentlemen Martin tried to emulate, his natural philosophical instruments (“eight related to electricity”) and timepieces were “assembled primarily to be of practical use, with just a few entertainment pieces.” Besides a variety of boats, Martin took interest in the latest craze, hot-air balloons; although they are not listed in the inventory. Martin was an avid collector of diamonds, fine rubies and other gemstones, and sumptuous textiles, furnishings and garments. Two factual errors: Monghyr is in Bihar, not Bengal (page 48) and “phiroza” is turquoise, not yellow (page 89). Martin today would be worth about £ 32 million sterling. It is not known how much the inventoried items fetched in the market but it was certainly enough, with other assets, to establish the three schools with an endowment of 18 lakh rupees.