Book: The Calcutta Kerani and the London Clerk in the Nineteenth Century: Life, Labour, Latitude

Author: Sumit Chakrabarti,

Publisher: Routledge

Price: £120

It is difficult to put down a book about the annoying clerk or kerani, a figure most of us have encountered with no little irritation. And, yet, there has been little academic work on this object of exasperation. It is here that this book fills an important gap, providing a capacious definition of who the kerani was, how he emerged, what constituted his practices, and reflecting on the extent to which he embodied both an embedded and quotidian bureaucratic practice as well as a subculture treated with derision, not unlike that other semantically loaded word — the mofussil!

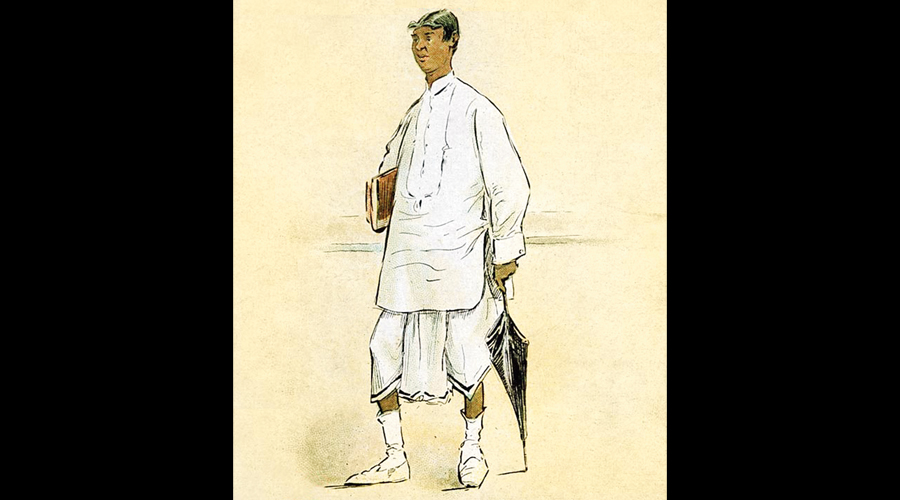

The Calcutta Kerani by Sumit Chakrabarti is a great read. It deftly balances an empirical study with dense theoretical ruminations, effortlessly transporting its readers to the dark and dank corridors of the kerani’s world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, replete with tattered files and grubby teacups.

The kerani inhabited an urban milieu, in this case the city of Calcutta, whose emergence and growth form an important backdrop. The colonial city was distinct from its other, non-colonial counterparts — education and bureaucracy gave Charnock’s city a different tone. Why this was so is subtly suggested but not explicitly explored. In part, it was to do with a set of new expectations on the part of the lower literati in Bengal, persuading them to gravitate towards the clerical profession; and in part, it was to do with the playing out of colonial policies and prejudices that forced the clerk to become the mean and grovelling figure everyone loved to despise.

The Calcutta Kerani and the London Clerk in the Nineteenth Century: Life, Labour, Latitude by Sumit Chakrabarti, Routledge, £120 Amazon

Inhabiting an ambiguous space in the long and celebrated lineage of munshis and karanams who had occupied a central place in the newly-emerging bureaucratic regimes of early modern India, the kerani was different — and, in the author’s words, a product of European colonialism. But what constituted this difference? The author takes us through the existing theoretical literature on colonial subjecthood, identity formation and marginality, and concludes that the clerk’s innate dispensability and his limited range of skills — stemming from a narrow and instrumental colonial education — were responsible for his marginalization. Caste did not matter very much in this process. In fact, there was a new redistribution of caste status across the hierarchy of colonial employment that produced a strange and inexplicable rupture between caste and status. Thanks to an imaginative reading of creative fiction and prescriptive literature, the author demonstrates that in Bengal one could not draw a link between caste identity and scribal practice. This meant that the kerani was neither bhadralok nor subaltern; he was a marginal, perhaps even invisible, figure but he was not subaltern in the conventional sense of the word although in life experience, he was emptied of all agency. With a tyrannical boss in the office, a nagging wife at home, and a life without leisure, his lot was not to be envied. The obsessive preoccupation with chakri (employment) and the abandonment of farm and factory left the clerk bereft of space and imagination — his conundrums conveyed brilliantly by the author’s reading of plays and primers on the kerani.

And yet, the kerani, we are told, remained absent in contemporary mainstream discourse. The reasons for the erasure are not adequately addressed and what we have is a reinforcement of the contradictory class location of the kerani, neither gentry nor subaltern. Equally conspicuous by its absence is any attempt to track shifts in the nature of the kerani’s employment or his self-perception. We know from the author that the clerk in London inhabited a changing office space from the middle of the nineteenth century and that he participated in the making of a liberal public. Are we to assume that nothing changed in the colonial city and that the clerk and the office he occupied in a city like Calcutta remained frozen in time and place? While the point about the kerani occupying a contradictory class position is well taken, this narrative does not allow for changes in context and location and limits itself to a stereotypical image of the clerk — lowly, amenable to only derision, and devoid of both buddhi (intellect) and bahubal (masculine strength).

As a narrative that attempts to humanize the clerk, the book is an important advance even if it does not entirely go beyond the stereotype. It uses a range of available sources, from the Kerani Puran to the Kerani Darpan, to flesh out the materiality of the clerk’s daily existence. At the same time, it leaves no stone unturned to display the author’s familiarity with theoretical ruminations on modernity, hybridity, mimicry and all the complex manifestations of colonial modernity. The tedium of navigating the complexities of this discourse is offset by a more humane narrative that rests on rich empirical detail, bringing alive the kerani, blurring the distinctions between a fictional Muchiram Gur and the real Shashi Chandra Datta, and making the book a fascinating read.