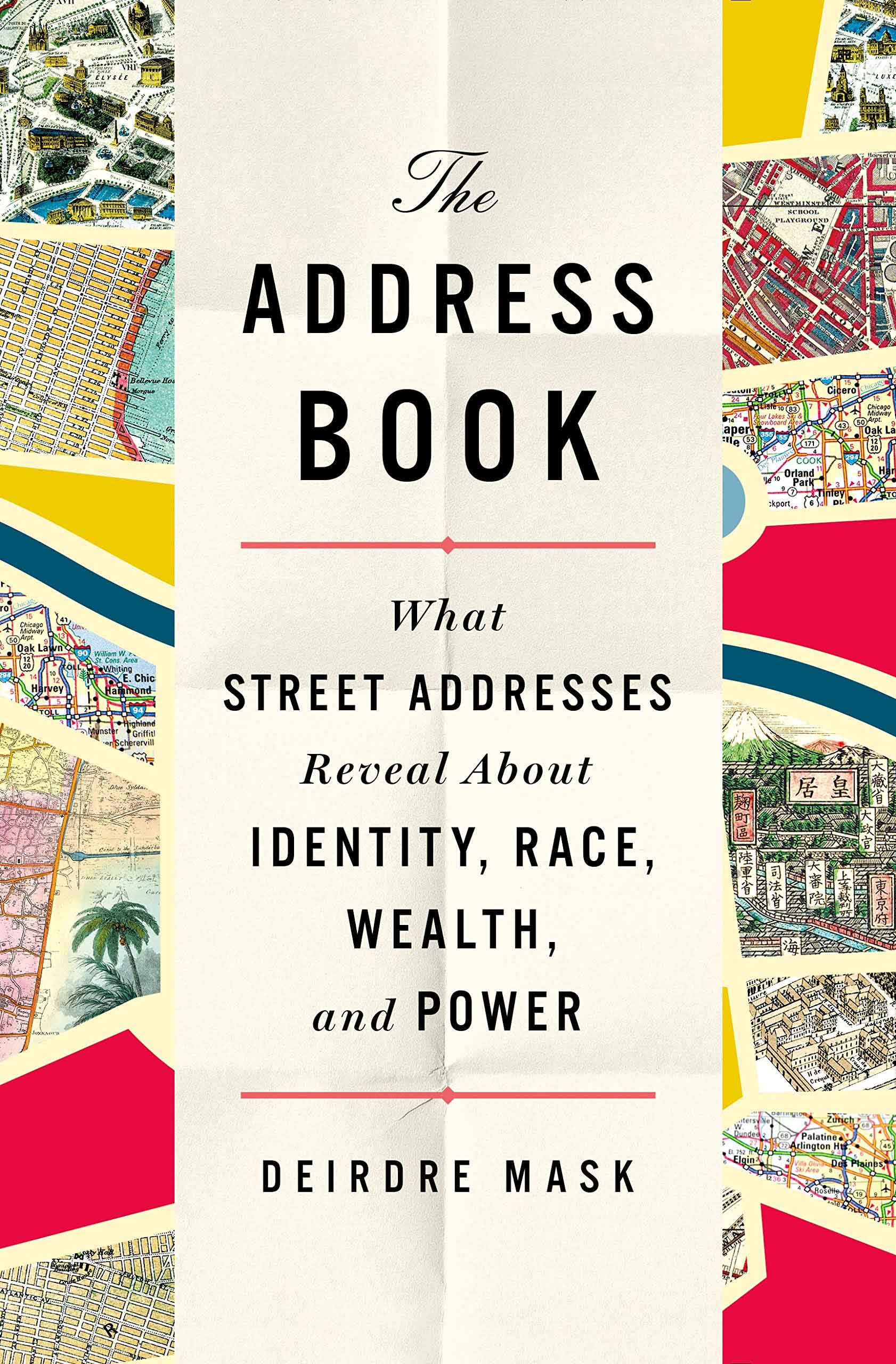

Book: The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal About Identity, Race, Wealth and Power

Author: Deirdre Mask

Publisher: Profile

Price: £16.99

Deirdre Mask offers a number of fascinating micro-histories of “... how the Enlightenment project to name and number our streets has coincided with a revolution in how we lead our lives and how we shape our societies. We think of street addresses as purely functional and administrative tools, but they tell a grander narrative of how power has shifted and stretched over the centuries.” The epigraph, a quote from Willy Brandt’s Left and Free: My Path 1930-1950, written about his left-wing, socialist, anti-fascist, refugee years, gives a quintessential preview of the political texture of Mask’s narratives; so does her acknowledgement of intellectual debt to Seeing Like a State (James C. Scott) and Paris as Revolution (Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson). Her firm conviction is that “addressing the world is not a neutral act”, and that naming the streets and numbering the houses have been part of State-formation. It has been so between late-eighteenth-century Europe and innovation of digital address, especially what3words in 2013. The State’s coercive initiative to name and number, perceived as “essentially dehumanizing”, provoked, for example, the late-eighteenth-century Genevans to resist by erasing painted names and numbers, even ‘defilement with excrement and hacking away with iron bars’. Universally, this was till people could be incorporated into the new culture of urban living and/or names and numbers were found to be useful also for a variety of radical politics, and for developmental interventions in the lives of the unaddressed.

The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal About Identity, Race, Wealth and Power by Deirdre Mask, Profile, £16.99 Amazon

Given Enlightenment’s historical complicity with colonialism, Mask does appropriately open with the present-day Chetla slums in Calcutta as she narrates State-directed introduction of addresses in various countries. It is widely acknowledged that address enables marginal people to access earning opportunities, voting rights and larger markets, that is, in their claims-making and short-distance social climbing. This has been precisely the reason for the elitist administration denying them an address lest this legitimizes their claims and contentious politics. Voluntary associations in search of the intended beneficiaries have to depend on local “exuberant direction givers”. For coping with cholera in Haiti in 2010, Doctors Without Borders had the same problem: the absence of the addresses of the sick poor. But location is so vital for epidemiological mapping, a prerequisite for stopping an epidemic; as it was for dealing with the same disease in Soho in 1854. Street address and house numbers do matter in development and containment of epidemics. But many miss out the State’s underlying persistent drive to know “what becomes of each individual from his birth to his last breath.” The Vienna history of street-naming reveals this universal process. But there is equally exciting counter-history of street names commemorating revolutionaries ‘championing equality, rationality and regeneration’ in Iran, Mexico, Spain and China; no less in naming and renaming Berlin’s streets as the city struggled to cope with its many pasts. Compared to this, Americans are happy with “numerical street names”. In Tokyo and South Korea, blocks are numbered, not streets. Both practices have their specific histories. Mask bares these all, bringing out how race, wealth and power play a critical role in address-setting across cities.

She is equally disturbed by commerce-directed digital address. For Chris Sheldrick, the man credited with devising what3words, the recurrence of men and women in music business “always getting lost looking for gigs” initiated the search for a more efficient addressing system. The relative deficiency in accuracy of location in terms of traditional address by names and numbers is sought to be compensated by perfect pointers to location, particularly in the “last mile” when the delivery man requests for “further directions” from the recipient. A linguist chooses three words — the people of a locality are most familiar with — with dots in between to signify their exact location in a 3-metre-by-3-metre square within a grid of such squares covering the entire world surface. The app-directed facility, now available in 36 languages including Bengali, marks the rise of private enterprise in the production of address — may be at the willing expense of the State. Mask is uneasy about the new technology of location depressing the place neurons, our internal GPS enabling us to navigate spaces creatively — “navigat[ing] without signposts” but through multisensory maps of the city, as the ancient Romans did or as London taxi drivers do. With use of the new technology, our collective memory about places will weaken. More grievously, this will undermine our concern for communities and their well-being. “Arguing about street names has become a way of arguing about fundamental issues in our society at a time when doing so sometimes feels impossible... We should keep talking about Karl Marx Street.”