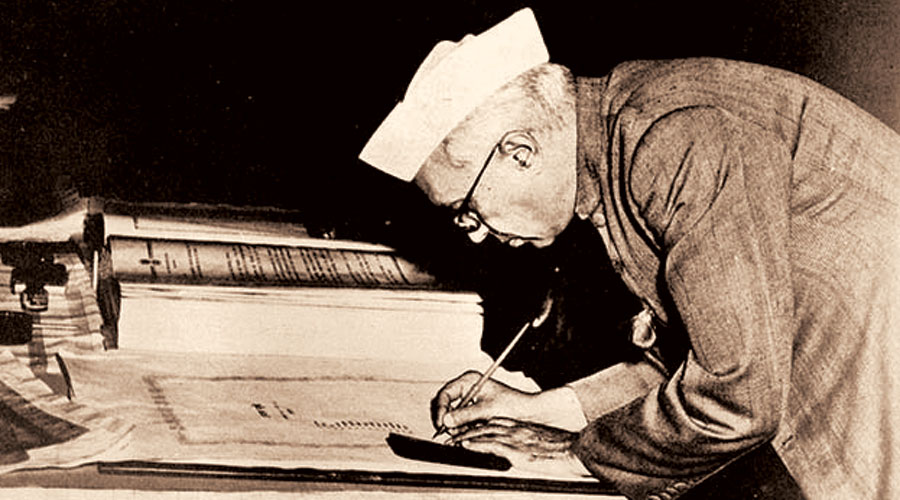

Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision of India and the world, it is safely assumed, is an antithesis of that pursued by India’s present prime minister. Such a claim is unlikely to invite the chaste indignation of India’s liberal fraternity or, for that matter, the far more lethal retaliations from bhakts. But is the line distinguishing Nehru and Narendra Modi inviolable? Could there have been an epoch in Independent India’s political trajectory during which specific historical conditions and political motives combined to make Nehru’s words and action mirror those of the incumbent prime minister? The answers — liberals and hawks would be astonished to know — are in the affirmative. Tripurdaman Singh’s scintillating examination of the First Amendment to the Constitution, a chapter that is often reduced to a footnote in magisterial accounts of modern India’s political journey, brings the legacies of Nehru and Modi uncomfortably close for their respective constituencies.

Indeed, Singh’s research reveals eerie convergences. Speaking to the All India Newspaper Editors Conference in 1950, Nehru had warned — Modi echoed this very point 70 years later — that rights cannot exist without obligations. In fact, the festering tension between the imperative to uphold civil and personal liberties that was articulated, Singh shows, as early as 1895 in the Constitution of India Bill and the Congress’s political project of social transformation forced India’s first prime minister, otherwise a champion of liberal ideas, to turn against the Constitution. This is, in a sense, an account of the shadow that falls inevitably between ideas and (political) praxis.

Singh sets the stage for the confrontation in detail. A series of court judgments that limited the Executive’s imperious reach was germane to the conflict. The government’s attempt to censor both The Organiser, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh-affiliated publication, and Cross Roads, a left-leaning periodical, had been undone by the Supreme Court; the abolition of the Zamindari Abolition Act and the State Management of Estates and Tenures Act in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, respectively, met with enlightened judicial resistance — led by the high courts of Allahabad and Patna — for going against the letter and spirit of Article 31 (right to property) and Article 14 (right to equality), seriously undermining the Congress’s social and economic programmes; the Madras High Court dealt a body-blow to the Communal Government Order that legitimized caste-based reservations in educational institutions by reiterating Article 15 (1) of the yet-to-be untrammeled Constitution. Hemmed in by a judiciary committed to protecting constitutional guarantees and the pressures of commitment to a political agenda, Nehru fell back on his bitter-tasting ‘remedy’: “[I]f the Constitution... comes in our way... ,” he wrote in a letter to his chief ministers in February, “then surely it is time to change the Constitution... ”

The battle, in spite of Nehru’s colossal political capital and the Congress’s electoral dominance, was spirited. Singh’s documentation of the heated parliamentary proceedings not only underscores the quality of debate and the fidelity to the very best of democratic deliberations but also challenges many of our — lay — perceptions of luminaries. Shyama Prasad Mookerji, deified by New India for his authoritarian beliefs, led the charge in the Constitution’s defence while exposing Nehru’s infirmities. “[W]hat he [Nehru] is going to do is nothing short of cutting at the very root of the fundamental principles of the Constitution which he helped, more than anybody else, to pass only about a year and half ago.” Acharya Kripalani, much to Nehru’s consternation, resigned from the Congress. Meanwhile, liberal icons — not just Nehru — bared their fangs, devouring their own creation — the Constitution. In a memorandum to the Cabinet Committee, B.R. Ambedkar — that beacon of equality and liberty — recommended that “the Supreme Court ought not to be invested with absolute power to determine which limitations on fundamental rights were proper...” The home ministry — helmed by the Gandhian, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari — suggested that every freedom enshrined in Article 19 should “be made subject to martial law”. And there was Nehru, of course, invoking the government’s right to distort the very foundation of India’s constitutional democracy to — the irony must be noted — protect the implosion of democratic India.

Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment to the Constitution of India by Tripurdaman Singh, Vintage, Rs 599 Amazon

The reverberations of this neutering of the original, unalloyed Constitution, Singh correctly points out, resonate to this day. The source of the Indian State’s repeated infractions on liberty through, say, the clause of sedition lies in the revalidation of Sections 124A and 153A that was brought about by the First Amendment in June 1951; the policy of Reservation, whose contentious application has, on several occasions, widened the cleavages that it purportedly seeks to address, received legitimacy through the sundering of Articles 15 and 29; Article 31B led to the creation of the controversial Ninth Schedule, a “constitutional vault” to store unconstitutional legislations.

It would be exaggerated and unfair to attribute the depredations of Nehru and his pliant peers on the Constitution to personal motive. That is the monopoly of the modern sevak. What Singh offers by way of explanation of this moral, collective capitulation — he should have been less ambiguous — is a set of possibilities. “[T]he biggest motivation was the establishment’s quasi-vengeful desire to enforce its will and show the Constitution and the judiciary their place in the pecking order... ” Elsewhere — this is the more likely explanation — Singh echoes the prescient Jayaprakash Narayan: “This three-way contradiction — between an expansively liberal… constitution, a heavy-handed… state, and a governing party with questionable commitment to fundamental rights” had remained unresolved.

This deepening fault line is yet to be resolved, if the hallmarks of New India are any indication. This reveals yet another ominous continuity. The sovereign will of the people — Nehru and now Modi command impressive electoral majorities — can, Singh shows, be used to bend the Constitution in a particular way.

Whether this ignoble history repeats itself remains to be seen. But what can be said — Singh can certainly claim credit for this — is that contemporary concerns about the demise of Indian liberalism have a precedent. Liberal India had bloomed, alas all-too-briefly, between January 1950 and June 1951.