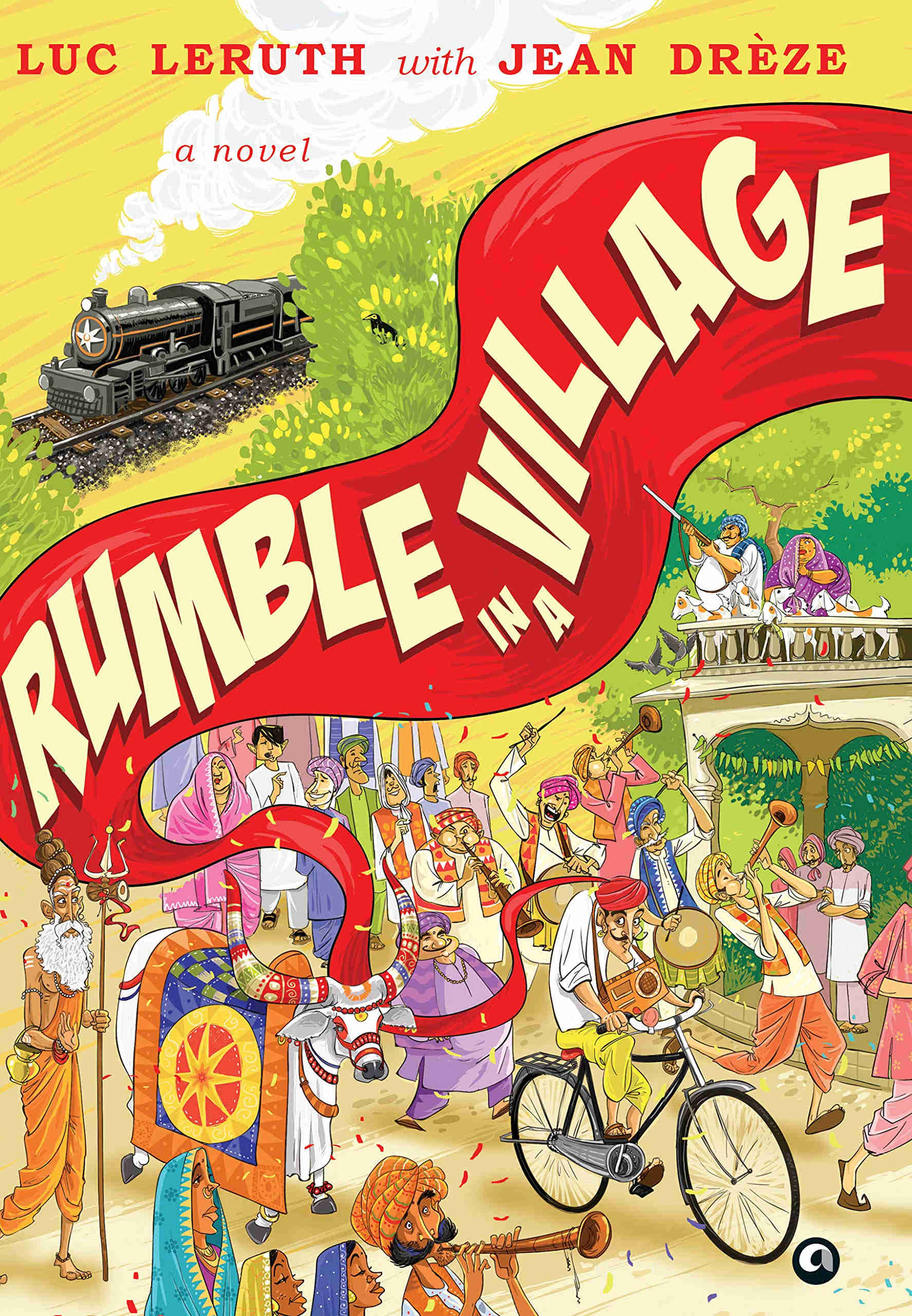

Book: Rumble in a Village

Auhtor: Luc Leruth with Jean Drèze,

Publisher: Aleph

Price: Rs 699

The setting of this non-linear novel is a village which, like many others in India, endures intransigent, everyday injustice. The narrator, Anil, comes to Palanpur (Moradabad, western Uttar Pradesh) from London in 1983 in connection with an inheritance from his unacquainted murdered uncle, Rajendra. His searches for the murderer, the motive, the murder weapon and the third bullet lead him to an intimate understanding of “the dark side of village life — jealousy, intrigue, corruption, violence and such... in a morass of class, caste and gender divisions”. He comes across a clue in his father’s notes on the village that there could be something “near the bed”. It turns out to be a makeshift hideout set up by Anil’s father during his visit to keep his written notes on the place, a hideout later taken over by Rajendra. Rajendra has concealed several books of accounts of his shady deals, remittances of loot to his accomplices, and even the tricks of misappropriation. In another hideout in a stinking corner close to the ferocious billy goat, Anil discovers pots containing “a plastic bag with gold coins, jewellery, and a wad of banknotes”. Anil easily infers that the ill-gotten money and the murder are closely related. What astonishes him is his uncle’s cunning because he conceals the hideouts yet keeps holes in the wall or at the window through which the curious can spy on what Rajendra does — or what he wants others to see “at times of his choosing”

Rumble in a Village by Luc Leruth with Jean Drèze, Aleph, Rs 699 Amazon

Information flows quietly through the village. In fact everybody, although silent, knows the murderer because Babu, son of Rajendra’s maidservant, Neetu, has followed him through the village that night. He is the police superintendent, BKS. This disclosure along with the location of the rifle and the third cartridge used in Rajendra’s murder comes in the wake of an altercation between BKS and Smita, who wants to refurbish a dilapidated building for a school for Dalit students. But that would deny BKS’s dacoit accomplices “a hideout for shady activities”; in any case, the dominant castes do not want chamar kids to study and a chamar teacher to teach. In a fit of anger and carnality, he tries to rape her. Anil takes photos of the sordid episode and hands these over to Babu. But the photos accidentally fall out of Babu’s pocket in the midst of a procession. Anxious about the unanticipated exposure, he tries to kill Smita. In the process, he ejects an old spent shell — the third bullet used in Rajendra’s murder. Anil leaves Palanpur in 1984 after allocating the retrieved money for the development of Palanpur and securing the release of the wrongfully implicated “less than dirt” chamar servant, Neetu.

The Epilogue lends the novel a different taste. Jiten Ram, a young boy when Anil was in Palanpur, writes him a letter a decade later to express apprehension that “the fire [kindled by Smita] may not last” and her contributions may go un-recorded in routine academic research on their village. Probably, the Palanpuris are looking up to writers like Anil to make amends for the omission; particularly because “your ancestors have a lot to answer for, and we, Dalits, have suffered more than anyone from their misdeeds.” They want nothing to be hidden: the name of their village, their names and the facts, “good or bad”, in the co-authored novel awaiting publication. Maybe they resent the culture of poorly-guarded secrets. That they want to make sense of themselves finds expression in their request for its Hindi translation, and for a WhatsApp number to receive their group photo for the book.