Book: Periodicals, Readers and the Making of a Modern Literary Culture: Bengal at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

Author: Samarpita Mitra

Publisher: Brill

Price: $146

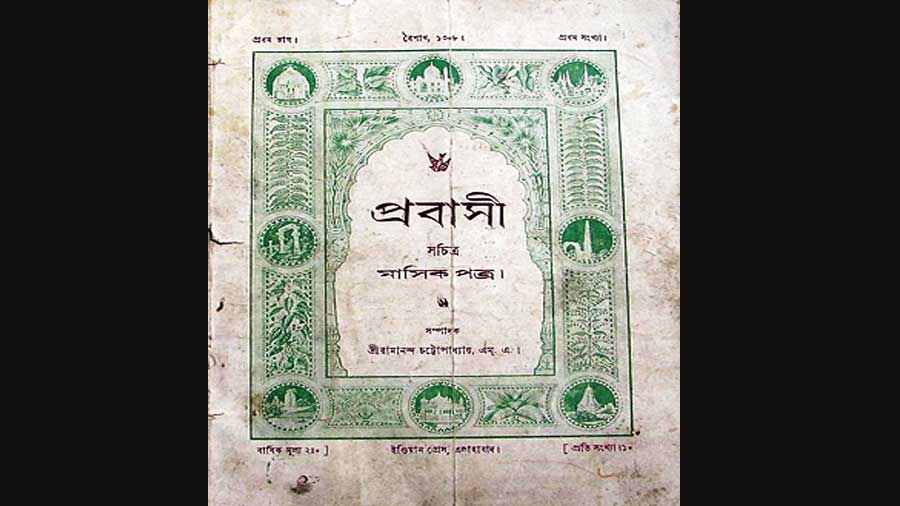

How many of us — we who read works of literature in self-contained book forms or as parts of collected anthologies — notice that Rabindranath Tagore’s Ghare Baire was serialized in Sabuj Patra over a year in 1915-16 and Sarat Chandra Chatterjee’s Pather Dabi in Bangabani for over three years during 1923-26? How many of us know that the poem-song, “Vande Mataram”, which would inspire generations of soldiers of freedom, first appeared in Bangadarshan, which serialized Bankim Chandra’s Anandamath over 1881-82, or that Abanindranath Tagore’s iconic portrayal of Bharat Mata first appeared on the cover of Prabasi in 1905 when the Swadeshi movement was sweeping through Bengal? The point, really, is that the literary periodicals mentioned here, and hundreds of others that flourished in Bengal for more than half a century, from the late-nineteenth century onwards, constituted a core element of Bengal’s print culture and shaped a range of things, including a new reading culture and aesthetic sensibility, a possible alternative to the colonial educational set-up as well as a new social solidarity informed by a nation-consciousness (jatiya jiban) that aspired beyond caste and religious identities. Samarpita Mitra’s well-researched exploration of these transformative elements plugs an important gap in historical literature on the cultural politics of modernity and nationalism in Bengal.

The book sidesteps the earlier, ‘archival’ approach to periodicals, exemplified by Benoy Ghosh’s classic, Samayikpatre Banglar Samajchitra, and excludes journals devoted exclusively to science, medicine, agriculture, industry or to specific caste-based associations. It concentrates, instead, on the samayik or sahitya patrika, which, with their combination of serial novels, poetry, and snippets of entertainment, helped normalize the colonial middle classes’ encounter with modernity. The later addition of criticism and discussion — like in the ‘Alochana’ section of Prabasi — opened up “a space of uninhibited exchange of ideas” where the parochialisms of caste, religion, and other inherited social systems could be interrogated. From here, it was only a short step to other imaginative possibilities, most importantly for a nationalism seeking to create its own cultural and aesthetic space that was modern yet distinctive from the West.

Periodicals, Readers and the Making of a Modern Literary Culture: Bengal at the Turn of the Twentieth Century by Samarpita Mitra, Brill, $146 Amazon

As opposed to the ‘low life’ of Battala literature, the English-educated Bengalis read, as Haraprasad Shastri famously said, little more than Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, and Shelley till Bankim Chandra’s Bangadarsan helped create as well as popularize the literary high modern. Two decades later, Pramatha Chaudhuri’s Sabuj Patra would bring on another moment of transfiguration by expanding this democratizing imperative. It was joined by other twentieth-century periodicals like Kallol and Saogat in holding out promises of emancipation from social afflictions and exploitations. In all, literary engagements mediated by these periodicals helped, albeit gradually, build public consensus on the need to reform various social norms and practices. This by itself was a big shift from the nineteenth century when questions on social reform were restricted to the older public domain of engagement with the colonial State. One of the strongest elements of Mitra’s book is in showing how the literary journals reconfigured those debates into a new discourse of taste and morality. Mitra deftly explores how the literary sphere negotiated, over more than a century, the various “threats” or “dangers” to the idealized bhadralok nationalist constructions of household and conjugality — ranging from the new aesthetics of romantic love in the late-nineteenth century to the more complex challenges posed by modernism and psychoanalysis in the period after World War I. It was through these negotiations that momentous transformations were wrought in the fraught relationship between nationalism and modernity.

In a significant point of departure, Mitra powerfully complicates and critiques unitary concepts like the “middle class” or the “imagined community” of nationalism. She argues that the Bengali public sphere was at once democratic and exclusionary, rendering a single, homogeneous literary culture impossible. Instead, she foregrounds the polyphonic nature of this domain, where women’s journals, Bengali Muslim literary periodicals, journals of various caste groups, and district journals jostled for space with the mainstream periodicals, all feeding into multiple, intersecting literary spheres, coexisting as well as competing with each other. Such nuanced unpacking of an archive, while clearly demonstrating the unevenness of the evolving class ideologies and identities of the indigenous middle classes, has a sobering effect on the usual paeans sung to the supposedly ‘transformative’ subjective agency of an educated and enlightened Bengali middle class. Periodicals, as Mitra shows, were catalysts of “social change and self-cultivation” and, in this sense, their roles went far beyond serving as mere “reflections” of contemporary social life, which is how scholars have tended to see them so far. In mediating imaginative explorations into social life as well as in opening up latent possibilities of change, the periodicals became agents of change in the same society that spawned them. This is a remarkable academic accomplishment, for which Mitra deserves our praise.

At 435 pages, the book is a weighty tome. It could perhaps shed a little of its weight and add a few more quality images from the humongous archive of Bengali periodicals. More importantly — given the fact that Brill’s Library editions are prohibitively expensive — it could perhaps spawn a cheaper Indian edition, which would be appropriate for a well-researched book on a literary product that in its time reached hundreds of thousands of readers.