Book: Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, From Cholera to Coronaviruses and Beyond

Author: Sonia Shah

Publisher: HarperCollins

Price: Rs 499

How do infectious diseases emerge and spread around the world? How can we prevent the next pandemic? While the original publication in 2016 aimed to push the reader to ask these questions, readers of the 2020 HarperCollins’ India edition will find in the book and in its comprehensive take on pandemics answers to the many questions we have all been asking over the last few months. Although one does not expect a single book or one person to answer it all, Sonia Shah’s Pandemic comes very close to providing a companion book that addresses a vast set of infectious diseases, from the spread of Cholera during the British colonization of Bengal to the outbreak of Ebola in Sierra Leone in the mid-2010s.

To tell a global and longue-durée story is a mammoth task but Shah deftly weaves the narrative threads over 10 chapters to tell a story that is at once personal and transnational, one that spans centuries, even going as far back as the beginning of life on earth. One of the strengths of the book is how interdisciplinary it is; Shah persuasively moves through natural history, genetics, bacteriology, medical anthropology and the history of public health in a narrative that remains entirely accessible to the non-specialized reader. Using case studies of nineteenth and twentieth century epidemics, Shah provides a nuanced sketch of the stakeholders of an epidemic, locating both practices and discourses of the State, multilateral institutions, bankers, politicians, early epidemiologists, local residents and migrants within the emergence, spread and containment of infectious diseases.

Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, From Cholera to Coronaviruses and Beyond by Sonia Shah, HarperCollins, Rs 499 Amazon

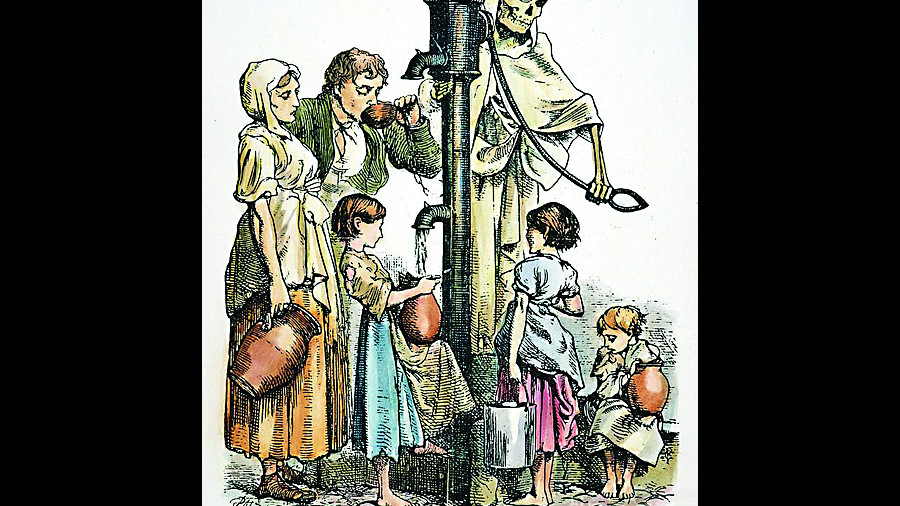

In spite of these notable achievements, there are noticeable gaps. While the few social history analyses will peak the interests of historians, explanations of how marginalized communities in the global South experience and respond to epidemics are largely unnuanced. For example, Shah does an expansive breakdown of Kuhn’s theory of paradigm shifts in science to explain why John Snow’s experiments on Cholera were not accepted by his contemporary scientific community. Indeed, even when governments in London and Paris eventually created their underground sewage systems, they did so not based on an acceptance of germ theory, but rather on existing concerns with miasma. Shah is — rightly — quite sympathetic to the paradigmatic changes in science, but it is disappointing to see her not extending the same sympathy to the people of Haiti, Uttar Pradesh or northern Nigeria, who, because of their lived experiences with global health campaigns and memories of encounters with colonial health officials, may have grounded suspicions of top-down global health programmes. The expanding literature on memory and history shows us that responses of “local” communities to top-down prescription cannot simply be classified as “ignorant” or “superstitious”. In this context, the near-equivalence of the ‘mistrust’ for public health experts on the part of Hollywood anti-vaxxers with suspicions of marginalized communities will draw criticism from anthropologists and historians. Before we ask how can we prevent future pandemics, we need to reframe our approach to infectious diseases. Scholars are increasingly observing that epidemics are experienced vastly differently by those whose lives are consistently entangled with infectious diseases as compared to the relatively privileged classes who can afford to live with an “amnesia” about epidemics.

Nevertheless, these remarks do not take away the book’s ability to ask timely and fundamental questions about the nature of a pandemic as a disease of unrestrained development, reified by unequal distribution of health resources across the world. The book will hopefully also raise further questions on the inequity in access to healthcare in our own country where public health is not yet seen as significant in electoral politics. For the optimism that the book upholds on our increasing ability to prevent further pandemics, I am tempted to argue that the “tools” for prevention still remain basic human rights to housing, health and dignity for all.