Book: Mutating Goddesses: Bengal’s Laukika Hinduism and Gender Rights

Author: Saswati Sengupta

Publisher: Oxford

Price: Rs 1,795

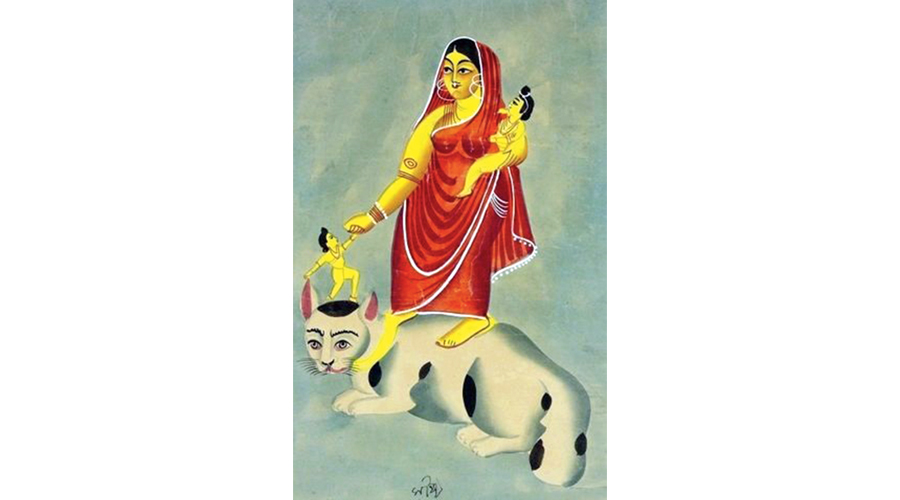

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.” That’s Sherlock Holmes, of course, and I was reminded of the second sentence while reading this book. In documenting Bengal’s “laukika” (popular) tradition of worshipping Manasa, Chandi, Sashthi and Lakshmi and associated vratas, this is a valuable piece of research. There are major Puranas (Maha-Puranas) and minor Puranas (Upa-Puranas). This is how Saswati Sengupta defines the Puranas: “The puranas, a corpus composed with the view to widen the social base of Brahmanism by selectively sanctioning non-vedic rituals, were instrumental in the ideological incorporation of the ‘others’ (p.12).” Itihasa (the Mahabharata, the Ramayana) and Puranas are believed to have been composed by Vedavyasa to popularize the Vedas. Hence, they are known as the fifth Veda. We also know agama texts coexisted with nigama texts and both strands coexist in the Puranas. How many Puranas are there? This is an easier question to answer for Maha-Puranas. There are eighteen. The names in the list of eighteen are almost standardized. Even when the list varies, Brahmavaivarta Purana will invariably be included in the list of eighteen Maha-Puranas. Why does the author consistently (on several occasions) refer to Brahmavaivarta Purana as an Upa-Purana?

It is fashionable to lambast Brahmanism. There is a difference between a brahmana and a purohita. In the Mahabharata, there is a section known as the “Dharma Vyadha Gita”, and that gives a reasonably good definition of who is a brahmana. Indeed, priests (purohitas) mess around with sacred texts, as they have in the case of Christianity. But indiscriminate usage of the word, brahmana, is best avoided. Perhaps one should read the “Yaksha Prashna” section of the Mahabharata, where the Yaksha asks Yudhishthira who is a brahmana. This is what Yudhishthira said in response: “If these traits, not even found in a brahmana, are seen in a shudra, he is not a shudra. One in whom a brahmana’s traits are not found, is a shudra, not a brahmana.” If society was stratified into this four-fold structure of the four varnas, why does Arjuna mention jati in the Bhagavat Gita? Why do the Dharmashastra texts speak of other varnas? When the British had their colonial census in 1881, why were many respondents stumped when asked which of the four varnas they belonged to? This is not a defence of patriarchy and consequent oppression. But it is a caution against facile generalization and straitjacketing into concepts Western scholars have found convenient. There are Gitas other than the Bhagavat Gita in the Mahabharata. One of these is known as Pingala Gita, spoken by Pingala, who was a courtesan. There is a section in the Mahabharata, which describes how the sage, Shvetaketu, instituted chastity in marriage that was non-existent earlier. In a book that doesn’t stick to its core research on Manasa, Chandi, Sashthi and Lakshmi but goes beyond it and analyses gender rights, it is important to mention these, as it is to mention women rishis who figure as composers in the Vedas.

Mutating Goddesses: Bengal’s Laukika Hinduism and Gender Rights by Saswati Sengupta, Oxford, Rs 1,795 Amazon

“Manusmrti, and its precepts, have remained a central iconic text in the sanctioning of caste and gender hierarchies, repression, and political subjugation (p.31).” “Normative Brahmanical literature prescribes stringent control of women’s ‘wandering about’ since caste purity as well as patrilineal succession is contingent upon the safely guarded wombs and women are presumed to have ‘fickle minds’ (p.305).” This last sentence is substantiated by quoting from the ninth chapter of Manusmriti. Let me quote from the third chapter. “Where women are honoured, the gods are delighted. But, where they are not honoured, all sacrificial rites are rendered unsuccessful.” “Fathers, brothers, husbands and brothers-in-law, who desire a lot of welfare for themselves, must honour and ornament them.” “Where the daughters sorrow, the lineage/family/household is soon destroyed. Where they do not sorrow, there is always prosperity.” On the Manusmriti, if one is not going to quote these sections, one is not being intellectually honest. By choosing facts to suit the theory, one undermines one’s own credibility. What of several texts with sections that state the mother determined who was a son (putra), not the father?

The book has valuable research on Manasa, Chandi, Sashthi and Lakshmi. But I think Sengupta has done an injustice to her impressive credentials by a) seeking a unified field theory on gender in India; b) quoting selectively; and c) assuming a linear timeline. “… The two empowering loci of Hinduism; the Sanskrit language and the male Brahmana. Both, the language and the caste-gendered figure, mark the exile of women from the privileged religious realm.” Surely, I should start by defining Hinduism. In a complex dharma, several strands simultaneously existed and continue to exist. Texts were composed by specific people, for a specific audience. I can pick up a textbook from an engineering college and argue that English literature (which Sengupta teaches) has been exiled from privileged educational realms. Excavations have revealed Devi temples that go back thousands of years. But these do not fit the neat theory. But that is also this book’s USP, because it will appeal to a Western audience that likes binaries.