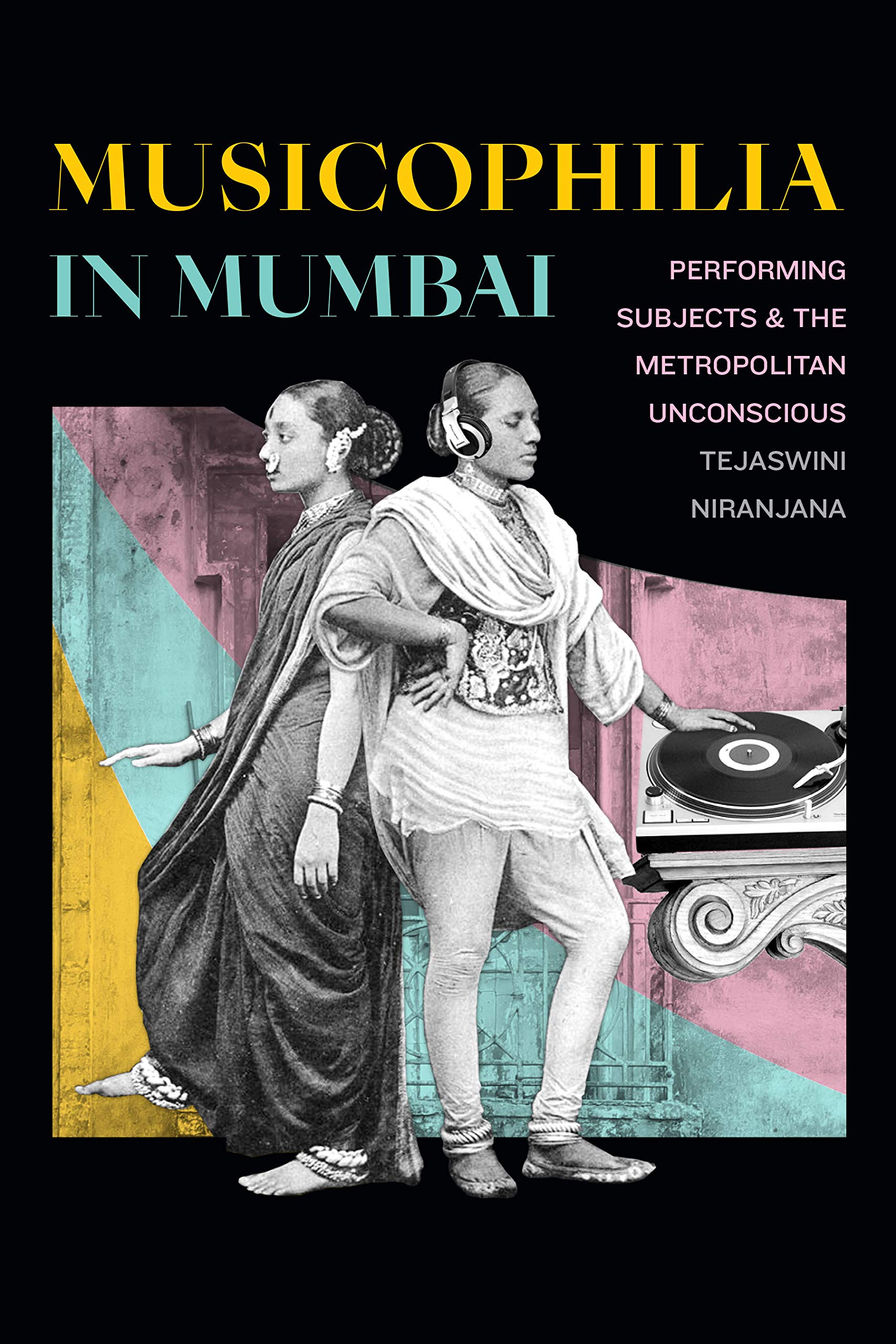

Book: Musicophilia in Mumbai: Performing Subjects and the Metropolitan Unconscious

Author: Tejaswini Niranjana

Publisher: Tulika

Price: Rs 695

For the discerning consumer, the current proliferation of texts on and about Hindustani Classical Music is a munificence worth exploring. Tejaswini Niranjana’s Musicophilia in Mumbai ought to occupy a prominent position within this largesse, thanks to its combination of excellent scholarship, accessible language, and sagacious approach. The subtitle, “Performing Subjects and the Metropolitan Unconscious”, is significant; the text talks about performers as well as those subjected to performances. The usual practice of tracing the movement of Hindustani Classical Music from non-urban to urban spaces, or from comparatively private to increasingly public spaces, has been set aside to focus on the coalescences and divergences of space in terms of the music within the metropolis itself.

The chapters appear to be built around the thought, memory, affect and motivation of making and experiencing music. The first chapter discusses the convergence of musicians from different parts of India to Mumbai in the colonial era. An important port city, Bombay offered opportunities to teach, to perform, to record, and to keep a tradition, if not a way of life, alive. Niranjana calls this particular urge and necessity “the passion for music”. This, in turn, inspired people with similar interests in listening, learning, and marketing of music to come together and form social spaces neither envisioned nor formed before. These shared spaces, a characteristic of urbanity, and the shared language of the inhabitants, gave rise to a new sense of identity based on that sharing. The discussion continues in the next chapter to take account of the kinds of physical spaces which accommodated the former, and their relationship to the development of the music. The photo-essay format of this chapter, along with the author’s interviews of concert attendees, material gathered from memoirs and newspaper advertisements and so on, builds a fantastic musical map of Girgaum in Mumbai.

Review: Musicophilia in Mumbai: Performing Subjects and the Metropolitan Unconscious by Tejaswini Niranjana Amazon

The third chapter deals with the core of the phenomenon of musicophilia — a fervour unambiguously called deewangee or madness. Niranjana’s proposition, tying in with the notion of developing psychosocial identity, is that this madness is an excess of subjectivity, which fashions the spaces around itself. Chapters four and five, when read in conjunction, reveal perhaps the most important concept in the book — that of rupture. A ruptured past, an effort to evoke its imagined glory in the face of rapid social changes, an attempt to weave it into the present, yet the present already a confirmation of the rupture from the past: this is the site of musicophilia. The manipulated image created by Jugal Mody for the cover art is an apt representation. The discussion on changing pedagogy down the years and pedagogy changing the people is not historically linear but interlinked and interpretive. The association between teacher and student, still force-fitted into the guru-shishya mould, is astutely read as a cooperative liaison between non-traditional musical subjects.

Of the more striking points made in this book, one is Niranjana’s expression of doubt about the Rasa theory of Sanskrit aestheticians being fully applicable to the musical experiences of evolving times. This doubt plays itself when newer audiences tend to articulate the same affect/s as previous generations. Niranjana’s point, that the new audience imitates the older audience in expressions, gestures, and phrases of appreciation in order to belong, is convincing. The other remarkable point is that unlike many others, this book ruminates much less on the musician-performers and musician-teachers than the customary practice of music pedagogy would deem favourable. The focus on the music lover, whether it is a loyal audience or a converted landlord, is clear and appreciable. However, one wonders, how much does the internalization of affects of an earlier era go into the repetition-rupture that Niranjana talks about? And secondly, no matter how much a text attempts to shed light on the latent hypocrisies of a particular pedagogy, how far is it possible to stay unbiased when the author is a product of the same system? Yet, this is not an old-world text like Amiyanath Sanyal’s Smritir Atale; the scholarship and the expressions are those of this age. If Sanyal’s text showed one face of musicophilia from an insider’s viewpoint, this shows another, with as much objectivity as possible. Instead of situating the modern musicophile as subject only to the highly personal and individualized notion of appreciative listening, Niranjana goes over the concept of the ‘social subject’. In doing so, Niranjana observes modernity to be different for different milieus, something that cannot be an umbrella term, nor can be used to denote a static phenomenon, and is still evolving. In this context, exactly how much of the city’s collective memory is open to the possibility and availability of successful introspection may continue to be a moot point, but the questions are bound to open up new directions of enquiry and scholarship.