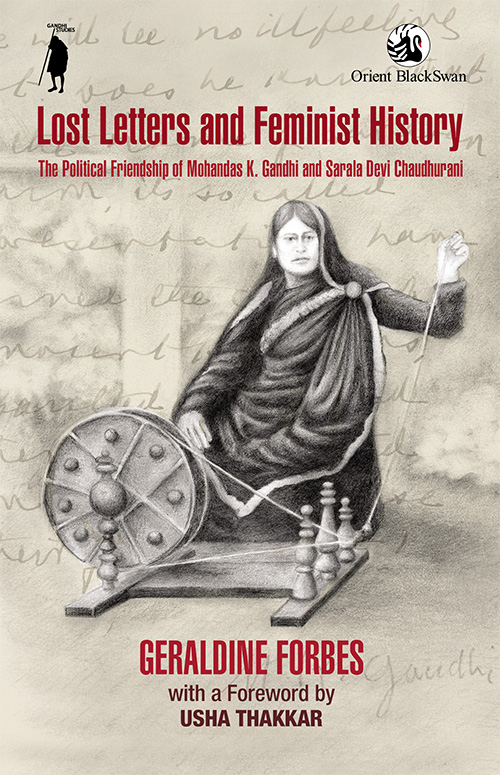

Book: Lost Letters and Feminist History: The Political Friendship of Mohandas K. Gandhi and Sarala Devi Chaudhurani

Author: Geraldine Forbes

Publisher: Orient BlackSwan

Price: Rs 595

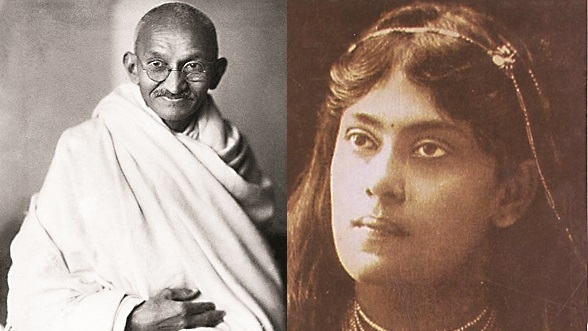

Geraldine Forbes’s book is a timely publication. M.K. Gandhi’s relationships with women associates have drawn the attention of many writers. Questions have been raised about Gandhi’s sexuality and an impression has been created that Gandhi failed in his experiments in brahmacharya. Forbes has dealt with such literature directly while analysing Gandhi’s relationship with women. The context is his relationship with Sarala Devi Chaudhurani, a woman ahead of her times. She was a close associate of Gandhi between 1919 and 1921. The most intense interactions between them in person and in correspondence happened in 1920. As the title suggests, Forbes’s specific purpose is to bring out the persona of Sarala Devi Chaudhurani in full and examine the political friendship between her and Gandhi. She argues that explorations in feminist history in India have left a gap by not fully studying this personality. She tries to fill this gap as a historian and is successful in her attempt. The writer rightly thinks that many people who worked in public life with Gandhiji have not been given due recognition in the history of India’s freedom struggle. This is particularly true in the case of his women associates who were eclipsed by Gandhi’s towering personality. In Forbes’s writing, Sarla Devi emerges as a powerful woman who influenced people during her time, especially women in Bengal and in Punjab.

The genesis of the book lies in Forbes getting hold of a set of letters from Dipak Dutt Chaudhry, the son of Sarala Devi, in 1976 and his consent to use them for publication. The set of 79 letters — 75 from Gandhi to Sarala Devi, 3 to her husband, Pundit Rambhaj Chaudhary, and one to her stepson — has been named the DC Collection. As a historian, the author has taken pains to examine the authenticity of the letters. She has satisfied herself before publishing them. She admits that she had no absolute proof that the letters — other than those in the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi and/or Day to Day with Gandhi by his personal secretary, Mahadev Desai — were written by Gandhi. But she writes that her training as a historian tells her that they are genuine.

Two chapters contain Gandhi’s letters to Sarala Devi covering the periods of January-May 1920 and May 27, 1920 to August 1945. The novelty of the book is that it contains letters that have not been published until this date. The CWMG is, thus far, considered to be the most authentic document containing letters from Gandhi to others. It sourced Gandhi’s letters to Sarala Devi from the Mahadev Desai Diaries that were not published when Volume 17 and 18 of CWMG were published in September and November 1965. It is not known whether Dipak Chaudhry had already deposited the manuscript of the collection of 79 letters in the National Archives or not. The reader is informed that he had the typed version of the letters, which he parted with and informed Forbes that he had deposited the originals in the National Archives. Since the CWMG does not contain most of the letters that were written in large numbers in May and August 1920, it can only be surmised that the manuscripts of the DC Collection were with Dipak Chaudhry until then. The importance of Forbes’s book is, therefore, enhanced. Another revelation that emerges is that the Mahadev Desai Diaries did not contain all the letters. This is natural because Gandhi was not always accompanied by Desai during the period in which these letters were written. Two distinct features of the letters from Gandhi to Sarala Devi are the frequency of the letters and the intensity of feelings in them. Gandhi addresses Sarala Devi as “My dear Saraladevi” from his first letter in January 1920 to “My dear Sarala” by March 23, 1920 to “My dear Sister” and, then again, “My dear Sarala” as well as “My dearest Sarala”. In most letters, he addressed her as “My dearest Sarala”. From March 23 onwards, he signed as “Law Giver”. His enthusiasm to see her as the most prominent woman leader of the Swadeshi movement is evident and he is seemingly dictating her to assume the role. The letters do reflect a man’s attraction towards a strong and powerful female. But the main role that Gandhi wished to play was that of a strict mentor. The letters are personal and reflect intimacy. By August 1920, the frequency of the letters and their intensity continued to be high but they also reflect the mentor’s disappointment in his disciple.

Forbes has examined the letters and referred to the CWMG with great care. She is aware that there was an attempt to bring out a revised edition of the CWMG in 1999. She may not know that it should not have been attempted according to the protocol set by the original team headed by Professor K. Swaminathan. However, the writer has argued that the soft copies of the revised version were easily accessible on the internet. It appears that she has used the 1999 edition volumes to compare the letters in the DC Collection with those contained in the CWMG volumes. It would have been proper for her to use the original editions of the CWMG volumes edited by Swaminathan. This reviewer has compared all the letters with the volumes in the original edition. Some more discrepancies also show up in the DC Collection that Forbes has missed. Nevertheless, such instances are few and hence the work done can stand the scrutiny. The endnotes provided at the end of the two chapters containing letters are very useful and help in establishing the authenticity of the DC Collection. But some questions remain. For instance, did Mahadev Desai take the dictation for some of these letters or were they written by Gandhi with Desai making a copy in his diary? Did Gandhi add with his own hand a few lines before dispatching them? Interestingly, some of the letters were written when Mahadev Desai was not with Gandhi. How did he access those letters? Did Gandhi keep copies of the letters he wrote? Another aspect that comes out clearly is that Dipak Chaudhry was not careful while getting the letters typed. Apparently he did not proofread the typed version well and did not compare them with the originals. The book remains important in spite of these. It is perhaps the only volume that contains so many letters. Many writers have sensationalized the relationship on scanty evidence.

Lost Letters and Feminist History: The Political Friendship of Mohandas K. Gandhi and Sarala Devi Chaudhurani by Geraldine Forbes, Orient BlackSwan, Rs 595 Amazon

Forbes’s book is also an important publication as it contains chapters on Gandhi’s relationship with women and a brief biographical sketch of Sarala Devi that precedes the chapters containing letters. The chapter on Gandhi’s relationship with women contains a review of what she calls the “changing historiography of Gandhi, especially in terms of his relationship with women and sexuality”. Soon after Gandhi’s death, prominent scholars and journalists wrote biographies and the works of Gandhi’s close associates were also published. Forbes argues that despite the fact that Gandhi’s relationship with women was under discussion during his lifetime and that Gandhi too discussed his sexuality in his autobiography and in his other writings, biographers and scholars did not discuss Gandhi’s sexuality in the first 40 years after his death. Gandhi’s contribution towards women’s emancipation and freedom was discussed generally and in feminist literature. In these earlier writings, Gandhi had been criticized for encouraging women in a patronizing manner. Subsequent feminist studies scrutinized Gandhi afresh. Forbes says that Madhu Kishwar was the most vocal about Gandhi’s sincere efforts to conform to his ideal of male-female relationships untainted by sexual feelings.

Interestingly, Gandhi’s sexuality began to appear in post-1990 literature. Sarala Devi appears in these writings prominently. It began with Martin Green and was followed by Girija Kumar and others, including Ramachandra Guha. Forbes has analysed the evidence examined by most writers and argued that they do not produce any clinching evidence that can prove that the relationship between the two was romantic or erotic. It is true that Gandhi’s relationship with Sarala Devi, especially during her stay in Sabarmati Ashram, had disturbed his close colleagues. Gandhi was also warned about it. Kasturba was disturbed too. Gandhi did write to Hermann Kallenbach and referred to Sarala Devi as his “spiritual wife”. Forbes says, “However, it is a stretch to read this that Gandhi wanted to divorce Kasturba, urge Sarala Devi to divorce her husband, and then take her as his wife.” Forbes also mentions Gandhi sharing his relationship with Sarala Devi with the American activist, Margaret Sanger. He may have confessed his fascination for her. But his fascination was more about seeing her as a dynamic woman political leader.

Forbes shows extraordinary maturity in discussing Gandhi’s sexuality and while dealing with the Gandhi-Sarala Devi relationship. She has not shied away from the literature that has tried to sensationalize the bond. She has reviewed such literature with equanimity. In this sense, her analysis is objective; she even allows readers to be their own judge in delicate places. In conclusion, she writes, “It is a mistake to discuss Gandhi’s fascination with Sarala Devi without reference to the political context, Gandhi’s conviction that control of his body was intimately linked to the future of India, or to Sarala Devi as a brilliant and fiercely patriotic woman.” In this, she echoes Bhikhu Parekh’s view that Gandhi’s sexuality was intimately linked with his goal of regenerating the nation. Most Western scholars would fail to see this point about self-regulation or practising atma sanyam in public life. Only Lloyd Rudolph and Susanne Hoeber Rudolph in their book, Postmodern Gandhi and Other Essays, have analysed the point convincingly.

Forbes’s chapter on Sarala Devi is a piece of in-depth research. Writings on Sarala Devi have not dealt with her life after she left Bengal. She had settled in Lahore, Punjab, after her marriage to Rambhaj Chaudhary, a prominent leader of Punjab. Forbes has written about this part of her life extensively. This is a useful contribution to India’s feminist history. The protest against the Rowlatt Act and the Jallianwala Bagh massacre brought the Chaudharys into political action and limelight. Gandhi’s fascination with Sarala Devi was on account of her actions in public. He saw her as Shakti. Gandhi travelled with her extensively in Punjab and to other parts of India. She was the first lady to wear a khaddar sari and popularize it. Forbes concludes by saying that Sarala Devi carried on with her work to emancipate women even after she fell out with Gandhi as she could not agree to follow what her mentor insisted upon. She was not a broken woman after Gandhi suddenly discontinued his interactions and ignored her. Her receding from public life had to do with the untimely death of her husband in 1923.

Forbes also states that missing and lost letters limit the understanding of the full story. Gandhi had promised to write to Sarala Devi daily during 1920-21, and had imposed on her that she should do the same. However, there is often a remark in these letters that some letters have not reached or some have not been received. The postal service is blamed for this.

Forbes makes the interesting point that Gandhi was physically weak during 1919-20 and wanted a strong personality to take the movements of Swadeshi and Khadi forward. He saw in Sarala Devi the power and hence called her Shakti. But when he recovered, and his disciple failed her ‘tests’, she became less essential. As for authors treating Gandhi’s relationship with Sarala Devi within the framework of infatuation and romance, Forbes says, “These terms, with their conventional cinematic rendering, do not and cannot explain or define Gandhi in his relationship with Sarala, or in fact, with Kasturba, Prema Kantak, Mirebehn, Sushila Nayar, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, or any of the other women who were close to him.” Forbes misses here only Millie Graham Polak, who, in Mr. Gandhi, the Man, wrote that she could confide in Gandhi what she could only with a woman friend.