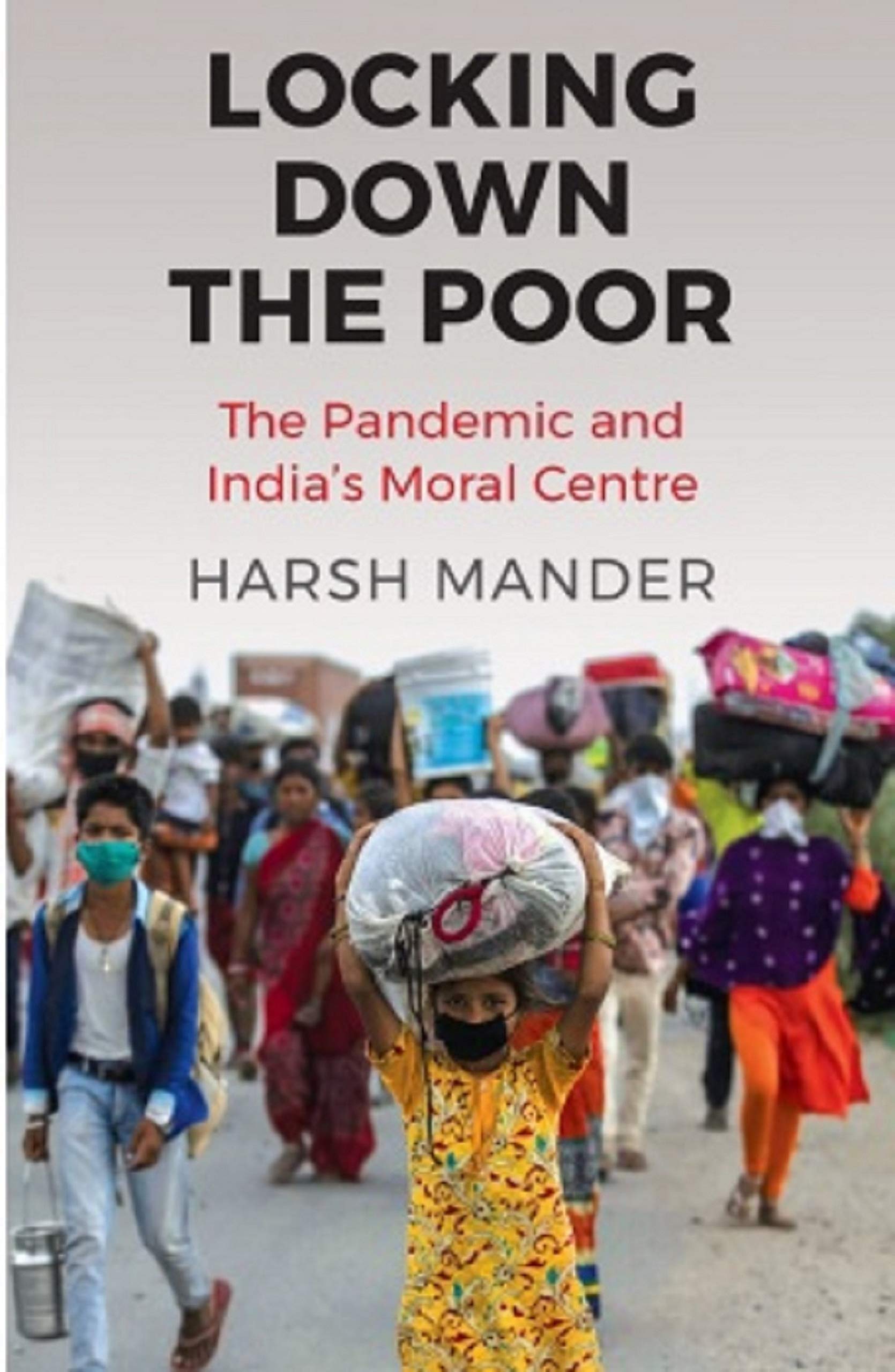

Book: Locking Down the Poor: The Pandemic and India’s Moral Centre

Author: Harsh Mander,

Publisher: Speaking Tiger

Price: Rs 399

It is possible that when we look back at 2020 a few years down the line, our personal memories — painful as they are for many — may obscure our ability to recollect with specificity the unyielding cruelties that were meted out daily during the lockdown. The winter preceding it had not been an easy one either, with the attack on Jamia Millia Islamia university, the riots in northeast Delhi, and repeated attempts to derail popular resistance to NRC and CAA. The pandemic, to use Arundhati Roy’s metaphor, served as an X-ray, bringing into stark contrast the injustices entrenched deeply within society and governance. Lest we forget, it is important to nurture archives that can serve as bulwark against mass gaslighting.

That is precisely what Harsh Mander’s Locking Down the Poor sets out to do. A product of his extensive on-ground engagement with vulnerable people before and during the lockdown, it reads like an empathetic and well-informed collective diary of a bad year. I would have said that its premise — the fact that the planning (or lack thereof) and implementation of the lockdown had an enormous class bias — is an obvious one but, alas, that is not so for many among us who could afford to look the other way and place their faith in the national rooftop rituals.

Mander’s writing is lucid, almost conversational. This does not, however, make the book an easy read as it challenges us to revisit some of the most tragic incidents from those months that were results of our collective failure. To those who stayed in touch with news from around the country, some of them would ring haunting bells: such as the image of scattered rotis on railway tracks between Badnapur and Karmad stations near Aurangabad, as on the morning of May 8 sixteen homebound migrant workers perished under the wheels of a goods train they did not know was running. Others — such as the account of fifteen men who had started camping inside Hume pipes on the banks of the Yamuna in order to escape the terribly mismanaged quarantine centres where the homeless became “qaidee” — are based on Mander’s interactions during campaigns he ran with his organization, Karwan-e-Mohabbat.

Without appearing heavy-handed, Mander succeeds in contextualizing these real-life stories within the broader arguments he posits across the twelve chapters of the book. His critique is directed both against callous decisions that the government took during this time and the more long-term structural inequalities that leave the most vulnerable people without any semblance of a safety net.

Locking Down the Poor: The Pandemic and India’s Moral Centre by Harsh Mander, Speaking Tiger, Rs 399 Amazon

In the failure to implement humane systems of food distribution on a large scale or the seemingly indiscriminate closing of state boundaries as millions tried to find ways of reaching home, Mander detects something more sinister than inefficiency: a deliberate denial of dignity and the dehumanization of the marginalized. The depressing narrow-mindedness of most lockdown narratives manifest itself in terms of class, caste, religious and gender privileges. The ‘Other’ must always take the blame. This could take the form of evicting a domestic helper in the dead of the night because she tested positive for Covid-19. It could also assume religious or racial overtones, such as the unfounded vilification of Muslims in the wake of the Tablighi Jamaat’s gathering in mid-March or the racist attacks on people from northeastern states.

Locking Down the Poor comes as a reminder of an ever-widening gap between the government and the people: a gap in communication, in mutual trust, and in meaningful action. Mander points to the prime minister’s refusal to host press conferences in favour of unidirectional, often confusing, messages sent out at whimsical intervals. But even at a structural level, he draws attention to the shortcomings of existing provisions that are supposed to ensure universal food security and labour rights as well as a lack of transparency in medical care. Envisioning these schemes from the point of view of the government rather than of the people, as Mander shows, often results in empty gestures that grab headlines but do not reach those in need.

Even as Mander interweaves anecdotes and analysis to narrativize the lockdown, by the end of each chapter one can almost see him struggling to retain faith in his own voice of rational critique. There is profound disappointment and frustration, but little anger. Notwithstanding the important questions it raises, Locking Down the Poor could have presented a more comprehensive picture had it acknowledged regional perspectives as well. For instance, the terrible set-backs faced by the people of Odisha and Bengal in the wake of Amphan find no mention. Perhaps it is time that the many small groups that showed exemplary dedication and courage (such as the Jadavpur Commune which at its peak served over 1,000 meals a day) begin to archive their experiences similarly to create parallel, resilient narratives.