Book: Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World

Author: Simon Winchester

Publisher: Harper

Price: Rs 899

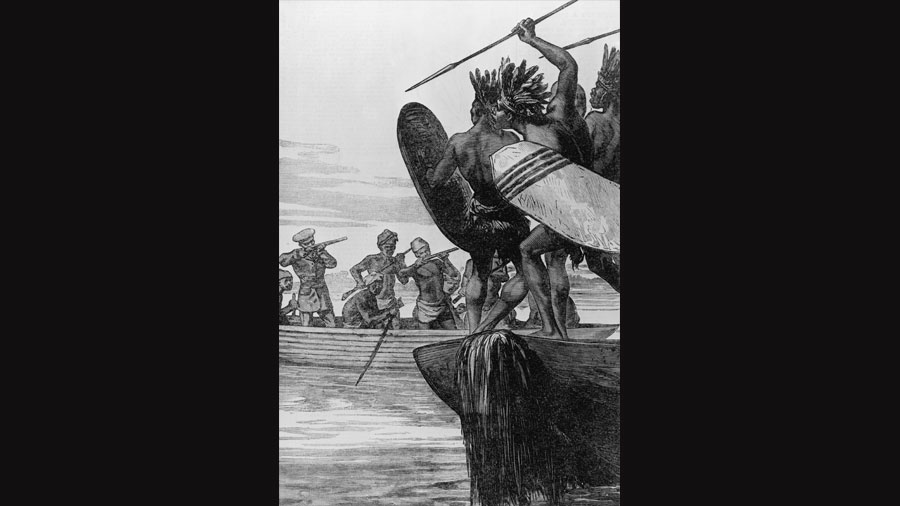

It’s a sweeping narrative, compellingly written and powerfully crafted. Land, by Simon Winchester, does what it sets out to do, drawing much-needed attention to how greed for ownership has shaped the world over the past centuries. How innocent and sensitive indigenous populations that tended lands in continents were plundered and dishoused — literally — from what had been theirs. The close-to-500-page narrative that spans several continents, even if its gaze is more thorough in some regions over others, chronicles the conflicts through history, illustrating how individual craving for possession and ownership, ideology, and a thirst for exploration and science have governed the motive.

Born out of discussions at home with his wife, Setsuko, over breakfasts, Winchester states that they were speaking “one morning about the iniquities of the then-current American immigration policy — concerning the degree to which land enclosure in Britain might have played a part in the eighteenth-and nineteenth-century transatlantic crossings.” The cruel irony, as the author puts it and can be seen in the decades’ old Israel-Palestinian conflict, is that those “who found themselves newly dispossessed on one side of the ocean had then sailed across it and settled again, but only promptly to dispossess those who already lived and prospered in what to the migrant Britons was a newfound and unowned country.” It is this and the other ironies that Winchester explores and recounts with a flair for minute detail laced with the quintessential quality of a gifted raconteur who crafts and laces language with a geologist’s gift of tracing science, topography along with the history of cartography that make this rich volume compelling to read. From Latvia to New Zealand, the Scottish Highlands to the Ukrainian steppe, to India and Japan and by way of America’s midwestern prairies, there are stories of power, ownership, control and discrimination everywhere, begging the question: ‘Who owns this land and how did it come to be owned?’

Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World by Simon Winchester, Harper, Rs 899 Amazon

Dedicated to Chief Standing Bear — the US government declared this Ponca chief in 1879 to be a ‘person’ under law but whose lands it took away — Winchester’s exploration takes us through the American West of the 1940s: the criminalization of 120,000 residents of Japanese ethnicity after Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, those who had travelled to the western islands at the turn of the century due to the impoverishment of cities like Tokyo and Yokohama suffering the ravages of the Russia-Japan war. Tenuous residents, if not citizens by then, having contributed tremendously to agricultural prosperity on the west coast, the chapter, “Concentration and Confiscation”, reveals how a majoritarian, white United States of America trampled on the rights of hardworking migrants through the centuries. While the cruelties of black slavery continue in retellings and the narrative of displacement and plunder of American Indians is still a story being pieced together in and outside the politics of the Reservation, the official apology to ethnic Japanese was made by President Ronald Reagan only in 1988 (carved into the sandstone of the US National Park Service memorial dedicated to American-Japanese patriotism in Washington, DC).

The preceding chapter, “Death on the Rich Black Earth”, brings to the reader the horrors of Stalinist Russia and ‘murder by starvation’, the ‘Holodomor’ (in Soviet Ukraine) and other cruelties heaped upon people. Man’s utilitarian use of land and nature is nowhere better typified than in the part that deals with the cynical nuclear contamination project of plutonic extraction created to fulfil the need of making the US’s nuclear arsenal — the soil, rivers, trees, and forests in and around the Rocky Flats Plant outside Denver in Colorado have been barren since 1992 and are nowhere near ‘cleaned up or reborn’. That neither the US nor any other country has learnt from this devastation is a bitter testimony to the fact that the real lessons of conflict over land remain unlearnt.

Yes, the story is about the push and pull of benevolent common stewardship: Winchester commends those nations — notably not Anglo-Saxon ones — that limit the notion of trespassing, allowing the right to traverse and enjoy a landscape that is “an inalienable part of human existence”. However, would the threat of climate change move us towards this? “Might the very fact of land’s newly realized impermanence not suggest to some that this could be the time to consider what has for so very long been well beyond consideration — the notion of sharing land, rather than merely owning it, outright?” asks Winchester.

While the politics of Land makes a strong call for collective imperatives, examples from both Australia and the US — not to mention India — where corporatized ownership is conspiring with the political elite to swallow common resources, suggest that the battles will rage on before humankind realizes which is the more prudent call.