Book: Kabir, Kabir: The Life and Work of the Early Modern Poet-Philosopher

Author: Purushottam Agrawal

Publisher: Westland

Price: Rs 599

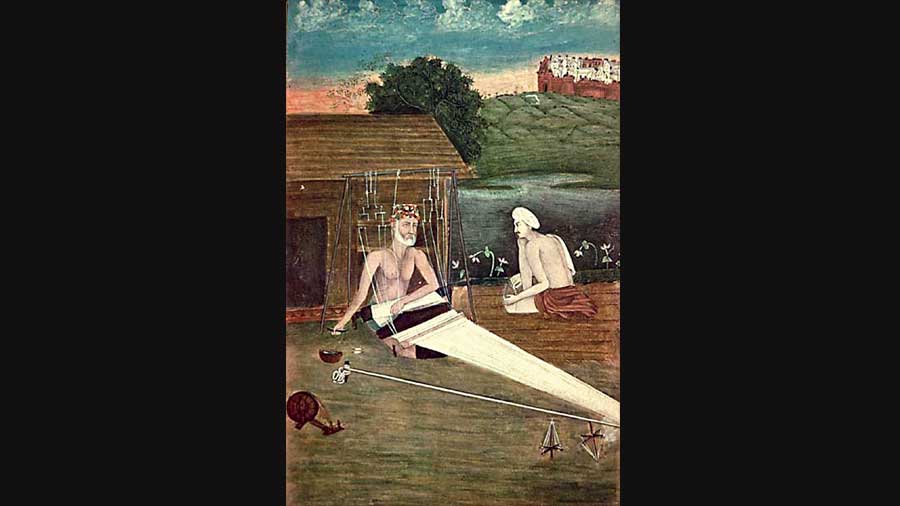

For more than four decades, Purushottam Agrawal doggedly pursued the interpretation of Kabir — the poet-philosopher who remained a weaver and householder despite innate literary prowess, spiritual inclination and a sizeable band of followers — first as a postgraduate student, subsequently as a doctoral candidate and, eventually, as academic and writer. Unsurprisingly, over this period, Agrawal added multiple layers to his earliest perception of Kabir being principally a “poet of protest”. Consequently, his assessment of the medieval Bhakti poet assumed weighty dimensions.

By the time Agrawal published Akath Kahani Prem Ki: Kabir Ki Kavita Aur Unka Samay (Love is an Unspeakable Tale: Kabir’s Poetry and His Times) in 2009, he concluded that his 1985 PhD thesis had been woefully inadequate. This book in English, twelve years later, after much coaxing from the mythologist, Devdutt Pattanaik, whose lilting illustrations liberally break the text across the book, is self-declaredly not a translation but an elaboration of Agrawal’s exploration of Kabir and his thoughts. The timing for this is apt, if only for the stranglehold and the omnipresence of organized religion in today’s India. At a time when religion is routinely milked by politicians to further or acquire political power and by business-persons to add to their profits, this book enables the reader to find meaning in a poet who made interrogation of organized religion and religiosity his brief. For a man who wanted to establish the universality of his ‘belonging’ even in death, we have witnessed the strange paradox of attempts to appropriate his legacy, by, most conspicuously, Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Agrawal elucidates a central belief of Kabir early on — whatever is to be achieved, or experienced, has to be done in the course of one life-span on earth; there was no afterlife in the poet-philosopher’s world view. Moksha, the illusive but much-chased goal in the Indian way of life, was for Kabir an objective when alive. It is this ability which perhaps enabled Kabir to talk and write about his own death. Much of this, of course, stemmed from his identity, a dual religious label that he wore — born a Muslim but living an extremely well-lived life as a Vaishnava but outside the domains of structured religion.

Kabir, Kabir: The Life and Work of the Early Modern Poet-Philosopher by Purushottam Agrawal, Westland, Rs 599 Amazon

Significantly, Agrawal not only explores the words and lines of the Kabir archives but examines and provides fresh meaning to those of his disciples too — for instance, Anantdas. The author delineates the lines of Kabir’s pupil that depict the tussle between the Hindus and the Muslims among the poet’s followers after his death over the ritual to be followed and the manner of ‘disposing’ of his corpse. However, one cannot but agonize that the pandemic of social prejudice and hostility in today’s India is but a heart-rending failure of a legacy that flourishes, sadly, only in the remote corners of contemporary India. Because Kabir’s legacy, which is put across in great depth, is not a living tradition among masses of people; it gets acquired by leaders who mix up history. Can one forget that not long ago, the prime minister talked of Kabir, Guru Nanak and Baba Gorakhnath being characters from the same period despite them living lives separated by centuries?

Agrawal argues forcibly that Kabir’s was not a voice or a sentiment that existed on the margins but that he had an immense following. The admiration of people for Kabir and

his lines stemmed in great part from him giving greater value to human characteristics and not the birth identity.

Agrawal started out as a Hindi ‘literary critic’. But this book makes it evident that he has acquired the capacity of an interdisciplinary scholar. As a result, Kabir is placed not just within the meaning of his word, but also his times and the polity of the era. The extraordinary ordinariness of Kabir’s life and his work is sadly, more often than not, communicated with the ease and simplicity integral to the poet’s lines. This is not just Agrawal’s limitation but also that of the scholastic system he has grown up in.