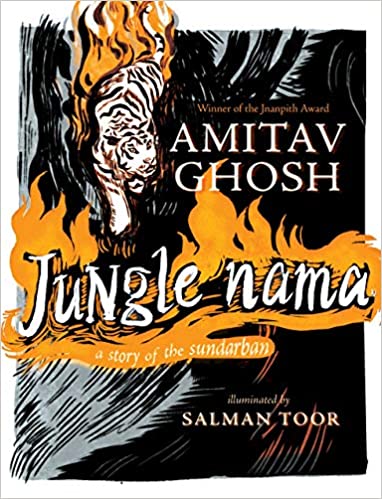

Book: Jungle Nama:A Story of the Sundarban

Author: Amitav Ghosh

Publisher: Fourth Estate

Price: Rs 699

In a letter to J.D. Anderson, which appeared in the October 1914 issue of The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Rabindranath Tagore wrote that informal spoken Bengali could not yet “swagger into polite society, with a caste-mark of printer’s ink on its pale forehead! But its throat throbs with song”. It was Tagore’s desire to “introduce the music of current speech” in his poetry “simply because popular language runs freely and gladly like a sparkling brook.” Amitav Ghosh arguably wants Jungle Nama, illuminated by Salman Toor, to do similar things. This is a verse rendering of an episode from the Bon Bibir Johuranama (“The Narrative of Bon Bibi’s Glory”), that recounts the legend of the benevolent goddess of the world’s largest mangrove forest. The Bon Bibi legend, refusing to fit into any single religious tradition, is a “marvel of hybridity” (“Afterword”, Page 76) and teaches the curbing of human greed to live in harmony with the natural world: “In Before Times, stories like this one would have been considered child-like... But today, it is increasingly clear that such stories are founded on a better understanding of the human predicament than many narratives that are considered serious and adult.” (77). Ghosh’s work has always been concerned with the environment; raising an eloquent and impactful voice against humanity’s great derangement. This book sets out to enact the “marvel of hybridity” that is the Sunderbans folk narrative, to rescue it from “Before Times” prejudice, enabling it to swagger into global society with the caste mark of printer’s ink and an internationally-acclaimed artist’s brush on its forehead. Like Tagore (and many others), his work has an avowed purpose. Unlike Tagore, Ghosh is not a poet.

This episode from the legend of Bon Bibi’s glory is about two merchant brothers, Dhana and Mana, and their poor young cousin, Dukhey. Dhana, as his name suggests, is avaricious. He decides to enter the forbidden parts of the forest, the realm of the monster, Dakkhin Rai, who manifests as a man-eating tiger, for wealth and profit. In the backstory, Bon Bibi and her brother, Shah Jongoli, had come from far-off Arabia in response to the prayers of the locals to rid them of Dokkhin Rai’s tyranny. They had marked out his territory and bound him inside it. Dhona ignores this restriction, and, when confronted with the ire of the tiger, gives up the unfortunate Dukhey as sacrifice. Bon Bibi performs her miracles, however, and everyone gets their just desserts.

Jungle Nama: A Story of the Sundarban by Amitav Ghosh, Fourth Estate, Rs 699 Amazon

Ghosh’s treatment of the allegory makes interesting choices. He chooses an episode from a folk myth, reworks it in English, in metre mimicking “the rhythms of Bengali speech” (75, which Bengali?) and with artwork as in medieval manuscripts. The living story (still performed as jatra plays in the Sunderbans) staggers under the burden. The greatest problem with Ghosh’s hyper-aware production is the language. It flows neither freely nor gladly. This is richly ironic, since everything — the narrator, Dukhey’s mother,and the plot outcome — stresses the miraculous powers of metrical speech. The choice of twenty-four syllable rhyming couplets for a “poyar-like meter” is baffling, since Bengali payar is fourteen syllables to the line and has a caesura after the eighth; and fourteeners had been traditional metrical vehicles for much of medieval and sixteenth century English verse already.

This strenuous quest for linguistic hybridity permeates the work to the extent of banality. Voices, vocabularies and registers jostle uncomfortably. A couple of examples must suffice. This is Dukhey’s mother’s reply to an offer of material compensation from Dhona for the loss of her son: “D’you think it’ll please me to gorge on sugar and ghee?/ Or that I’ll be consoled by fine alliballie?/ Even a river of richest dasootie,/would not be enough to serve as my dastoorie.” (61) This is perhaps the most emotionally charged moment of the story, a bereaved mother’s heartbroken outburst. Under the weight of Ghosh’s erudition, Dukhey’s mother’s devastation and outrage are reduced to a piquant play of Laskari terms highlighting the commodification of human life. The poor woman is truly hard done by. Equally telling is Dokkhin Rai remembering “[…]how he’d lain then, clasped, corralled and canting.” (54) This is obviously intended to invoke Macbeth’s desperate “cabin’d, cribb’d, confined” in the famous banquet scene (Act 3, Scene IV), but the laboured performance topples the allusion into ridiculousness. Salman Toor’s drawings were possibly of “luminous intensity” (78) in colour, but amount to little more than vaguely Oriental splotches of black and grey ink on the printed page.

In the Sunderbans, people call living off forest produce as “doing the jungle.” It is a risky business and jungle “doers” are regarded with wary respect. For all its good intentions, Ghosh’s doing of the jungle fails to bring in a rich haul.