This collection of the first 10 Ambedkar Memorial Lectures — they are organized every year on May 14 by Ambedkar University Delhi — is a valuable addition to the scholarship on the lives, times, thoughts, actions and continuing influence of a man whom Bhikhu Parekh, who delivered the first Ambedkar Memorial Lecture in 2009, rightly described as “not an easy person to understand and deal with”; an individual whose enduring legacy arguably stems from the fundamental distinction he drew between the “independence of the country and [the] independence of its people”.

The Introduction by Valerian Rodrigues, subtitled “Ambedkar as a Scholar and Ambedkar Scholarship Today”, begins by making the germane point that “Ambedkar was a quintessential university person” who was “integral to an academic culture of great significance that has few parallels in the global South”, and goes on to give brief expositions on Ambedkar’s own scholarship and scholarly method, ongoing academic research on Ambedkar, including philosophical and methodological studies, before discussing the ideas, opinions and issues that inform the 10 lectures gathered in this book. In itself, Rodrigues’s introduction can serve as an entry point to a study of Ambedkar and his intellectual legacy for any scholar.

The lectures themselves, as may be expected, vary considerably in their approaches to Ambedkar and everything he stands for today, with some engaging directly with his legacy (Parekh; Upendra Baxi on the “insurgent reason” of Ambedkar; Gopalkrishna Gandhi on what it means to “lead” in India; Aruna Roy on “unbridled capitalism”; Gopal Guru on the notion of an “exemplar”), while others use Ambedkar to talk of issues that may or may not be directly connected to Ambedkar but which can fruitfully be (re)examined in the light of the words and the work of Dr Ambedkar (Veena Das on the claims of citizenship; Deepak Nayyar on discrimination and justice; Ashis Nandy on oppression and the dialogue of cultures; Romila Thapar on civilization and/as history; Homi K. Bhabha on “the burdened life”).

Conversations with Ambedkar: 10 Ambedkar Memorial Lectures, edited by Valerian Rodrigues, Tulika in association with Ambedkar University Delhi, Rs 750 Amazon

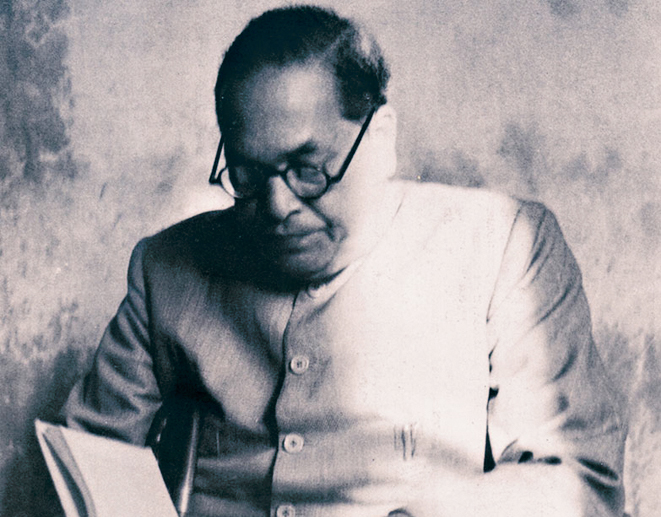

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar’s life was about as full of contradictions and paradoxes as can be imagined, and, thus, in many ways, can be read as an allegory of the new India that he helped fashion and put on a sound legal and economic footing. By far the best educated of all the founders of Independent India, he was, among other things, an economist, political analyst, lawyer, educationist and, perhaps most significantly, a social reformer who left his mark on virtually every aspect of modern Indian life. This has, naturally, led to attempts to co-opt him by diverse groups, political parties, social movements and so on, ranging from those fighting for the rights of the poor and dispossessed to opponents of Article 370, to defenders of the Partition. In such efforts, it has perhaps been inevitable that questions of identity, authenticity, lived experience and the right to speak on behalf of such groups by those who do not themselves belong to them have arisen and continue to arise even today. In fact, after the seventh Ambedkar Memorial Lecture delivered by Aruna Roy, the invitation extended to Romila Thapar for the eighth was opposed by the Dalit Bahujan Adivasi Collective, which wrote an open letter to the vice-chancellor of Ambedkar University Delhi, protesting what it saw as “certain exclusionary practices” wherein “when one looks at the list of previous speakers of the AML [Ambedkar Memorial Lectures], it is surprising to find that the University has not invited even once, a speaker belonging to Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi, minority and other such oppressed sections of the Indian subcontinent”. Maybe this led to an invitation being extended to Gopal Guru for the very next (the ninth) Ambedkar Memorial Lecture, but then again, maybe not.

A brief review such as this cannot hope to do justice to the many issues raised, dissected, discussed and debated by the 10 eminent speakers whose lectures are reproduced here, let alone take issue (as perhaps one must) with some of their positions; nevertheless it is perhaps worth pointing out that in none of the lectures is there an uncritical acceptance of any of Ambedkar’s words or deeds (as often happens even today, especially among those who use Babasaheb as an authority to plead their own case), and this, more than anything else, allows this volume to be read as a kind of invitation to a conversation, and a debate, among those who believe there is still much to learn from what this remarkable man thought, wrote, did and did not do in his relatively brief life. Gopal Guru tells us in his lecture (“Is There a Conception of the Exemplar in Babasaheb Ambedkar?”) that Ambedkar did not really wish to be an ‘exemplar’ for others, even though he had already become one in his lifetime; he wanted instead every person to be ‘atta dippo bhava’ (‘be a lamp unto yourself’ in Ambedkar’s use of this Buddhist phrase, rather than ‘be an island unto yourself’ as would be the literal translation from Pali). This volume can help us shed some light not only on our lives and our selves, but also on these contradictory, complicated and confusing times in the life of our country and, indeed, that of humanity itself.