Book: Black Wave: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Forty-Year Rivalry That Unraveled Culture, Religion, and Collective Memory in the Middle East

Author: Kim Ghattas

Publisher: Henry Holt and Co

Price: Rs 2,400

Kim Ghattas’s book is, indeed, a significant contribution to the vast historiography of the contemporary Middle East. It explores the religious-political dynamics of the region from inside rather than the outside — principally the United States of America and Israel. Situated largely within the discourse of intra-Islamic competition between Shia Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia since 1979, it powerfully demonstrates how the Islamic discourses mediated through State politics have catastrophically impacted the political stability of the region and everyday Muslim pluralistic lifestyles that the region had enjoyed as recently as the 1960s.

The work spares the readers of academic density and introduces relatively less-known but central figures and events of the contemporary history of the Middle East — from Lebanon, Syria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Egypt to Pakistan. The long-drawn journalistic experience of the author lets her make use of a relatively untapped historical source — oral testimonies — in her narrative with fluidity. One of the boldest assertions of Ghattas is that the current geopolitical dynamics of the Middle East, which owes a great deal to the Shia-Sunni or Iran-Saudi conflict, is to be explained not as “inevitable and eternal” but as a distinctly historical conjuncture that unfolded in the latter half of the twentieth century. Justifying the same with references to oral testimonies as well as a conscious evasion of academic standards must have been a difficult task. The strength of the book lies in its detailed historical exploration of horizontal and vertical interconnectivity of empires, governments, political Islamists, nationalists, secularists, traditionalists and others in contributing — mostly violently — to political events across the region.

Some aspects of the work shine through. But the book ignores the larger role of the political economy, classes, groups, tribes, demography and sub-regionalism in the making of events since 1979. This could possibly be owing to the fact that in many ways the history of Middle Eastern nation states is also the history of the making and the unmaking of the State from the above. The conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia should not have been analyzed so monochromatically: “both countries wield, exploit, and distort religion in the more profane pursuit of raw power.” The instrumental use of religion is not specific to Middle Eastern regimes; India was the first country in the world to ban Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. In fact, one of the major questions that arise in the scholarship of religion today, something that has not been dealt with in the book, refers to the problem of what is religion itself when it is being mobilized for anti-people, State oppression while, at the same time, serving as the ‘weapon of the weak’? Is religion or specific traditions of Islam necessary for mediating the field of power? Does it also hold anti-power acumen? Addressing these questions would have made the work richer.

Black Wave: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Forty-Year Rivalry That Unraveled Culture, Religion, and Collective Memory in the Middle East byy Kim Ghattas, Henry Holt and Co, Rs 2,400 Amazon

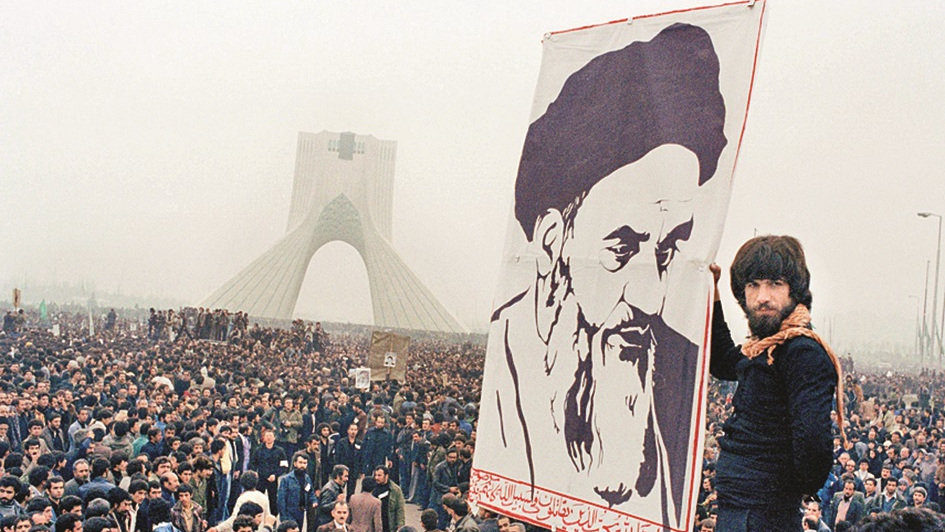

A major lacuna in the organizing principle of the narrative is evident when we see that the narration of three events that are its focus — “the Iranian Revolution; the siege of the Holy Mosque in Mecca by Saudi zealots; and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the first battleground for jihad in modern times, an effort supported by the United States” — is done by referring to leaders and socio-political elites, the parties active in the region, their agenda, ambitions and fallings: in short, the dynamics of the public sphere and/or the civil society. The dynamics of the more significant section that makes that sphere — “the crowds in the battle of oppression”, “the devoted followers… [who] came by bus and by car, travelling for hours, some for more than a day, across a small country without a public transportation” — are left unexplored. Those who are considered the protagonists of the book and of this public sphere — the “intellectuals, poets, lawyers, television anchors, young clerics, novelists; men and women; Arab, Iranian and Pakistani; Sunni and Shia; most devout, some secular, but all progressive thinkers who represent the vibrant, pluralistic world that persists beneath the black wave” — were also victims of the conservative shift since 1979 in the politics of the region and the story, inevitably, becomes one of persecution of the liberal-progressive sections of the public sphere by conservatives who come to occupy the State. The problem that arises with such a watertight compartmentalization is that such binaries do not pass the test of historical dynamism. For example, we may consider how, in the making of the Iranian Revolution, the so-called conservative, Ayatollah Khomeini, himself flirted with liberal-progressive and left-liberal ideologies in order to garner the support of the liberal, progressive, left and radical left segments of civil society for the anti-monarchical struggle.

Notwithstanding these criticisms, some of the aspects of the work deserve credit. For one, the book, given the vast historiography and conspiracy-stricken intellectual tradition of the region, doesn’t blame the entire debacle of the Middle East since the latter half of the nineteenth century on the West. Rather, after asking, “What happened to us?” it says, “We did it to ourselves”.

Ghattas draws inspiration from the emerging voices of dissent, tolerance and pluralism to overcome this phase of the ‘Black Wave’. The book is a must for any student of international relations and Middle Eastern politics.