WOMEN’S RIGHTS ARE HUMAN RIGHTS

In 1995, member states unanimously accepted the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, a landmark twelve-point agenda that calls for women’s full civil, political, economic, educational, and reproductive rights. It also calls for special protection of girls and the right of all women to live without the fear or fact of gender-based violence. Implementation has been slow, as slow as snails. Much of human rights work involves breaking down walls — the walls of silence, of complicity, of ignorance. There was no better place to do that than at the United Nations and no better way than to lead by example. To truly help women in developing countries, the United Nations needed to target our limited resources and maximize delivery of aid and expertise. I thought often about my mother’s young life and how hard every day must have been. This forged my unshakable belief that development initiatives must focus first on women.

I put women’s and girls’ health and equality at the center of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), knowing that no society can prosper if half of its people are unable to contribute or benefit. The 2015 SDGs are a package of seventeen goals meant to eradicate the extreme poverty afflicting 10 per cent of the global population by 2030. More than 730 million people live on less than $1.90 a day. The initiative builds on the 2000 Millennium Development Goals and takes a broad, systemic look at development and holds governments to a timeline to improve sanitation, education, nutrition, and access to health care. Several Sustainable Development Goals explicitly address women’s urgent needs, such as access to reproductive health services and equal access to education and legal protections.

Historically, women have suffered disproportionately in the poorest societies where they are often marginalized, disenfranchised, and abused. I was initially disheartened that some member states still could not accept the reality and centrality of women’s and girls’ basic human rights. Until governments prioritize women’s health and civil rights, I told them, progress would be elusive and equality would remain a dream for the future instead of a reality today. No single issue ties together the security, prosperity, and progress of our world more than women’s health. Initiatives to make childbirth safer are intuitive and compassionate, but some world leaders didn’t seem to fully recognize the risks of reproduction, even in their own countries. I launched Every Woman Every Child (EWEC) in June 2010 with $40 billion in pledges to reduce maternal and child mortality by sixteen million and prevent an estimated thirty-three million unwanted pregnancies over the next five years. I thought of my mother’s lifelong pain at losing two pregnancies and vowed to put the United Nations global infrastructure to work to make this tragedy a rare exception rather than a fatalistic risk. It is indefensible in the twenty-first century that a woman still has to risk her life to bring a new life into the world. This truth motivated me and so many others before me to reduce infant and maternal mortality in the developing world. As I often told diplomats and world leaders, there is no reason a woman giving birth in South Sudan or Afghanistan should be any less safe than a woman in Sweden or Australia. When my own three children were born, I was grateful to know that Soon-taek was in a hospital with skilled attendants. I can’t imagine how my father weathered his wife’s eight pregnancies, three of them during Japan’s colonialism.

It is unacceptable that some 300,000 women still die during pregnancy and childbirth every year. This figure is shocking. Sexual assault, fistula injuries, early marriage, and slavery are equally unacceptable. Women-focused NGOs now have a foot in the door, and they have grown to be effective advocates and information sources. The United Nations could not have made these gains without the NGOs and other organizations that share their strength with us, including research and anecdotal information from program areas, an existing network to deliver medication or services, political goodwill, and the best practices for working in remote areas with little infrastructure. Media have always been important in the struggle to legitimize “women’s” concerns; they are an unparalleled source of information and images. I participated in several events organized by The Guardian newspaper in 2014 related to their series on female genital mutilation. Local media, radio, and other communication sources also reinforced the message that women are equals and must be treated with respect. My own advocacy took various forms, but the message was consistent. I spoke about women’s issues in bilateral conversations with world leaders and from every podium in the UN and around the world: the General Assembly, World Bank, World Health Organization, regional summits, and countless international conferences.

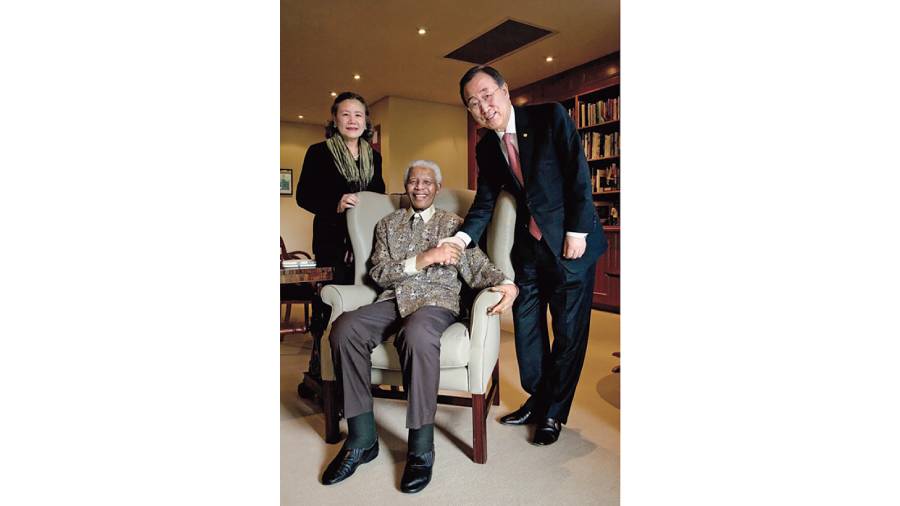

The media has quoted me hundreds of times on the importance of equal rights, education, investment, ending violence, and spacing children. I am grateful to Soon-taek for her determination and support, particularly during my first term. My mother-in-law, who lost her husband during the Korean War, taught me about passion and will, but my wife has shown me the power of patience. It was Soon-taek who encouraged me to be more generous and understanding about women’s lives. She pointed out that men have ruled the planet throughout our history, and now women are beginning to raise their voices. “Why are men so narrow minded?” she asked. “We are men’s mothers, wives, and daughters. Women are trying to elevate our status to equal men’s.”

Ban Ki-moon is a South Korean diplomat and former foreign minister who served as the eighth Secretary-General of the United Nations from January 2007 to December 2016. His book Resolved: Uniting Nations in a Divided World launches on November 18 by HarperCollins India