Book name: Tales of Hazaribagh: An intimate Exploration of Chhotanagpur Plateau

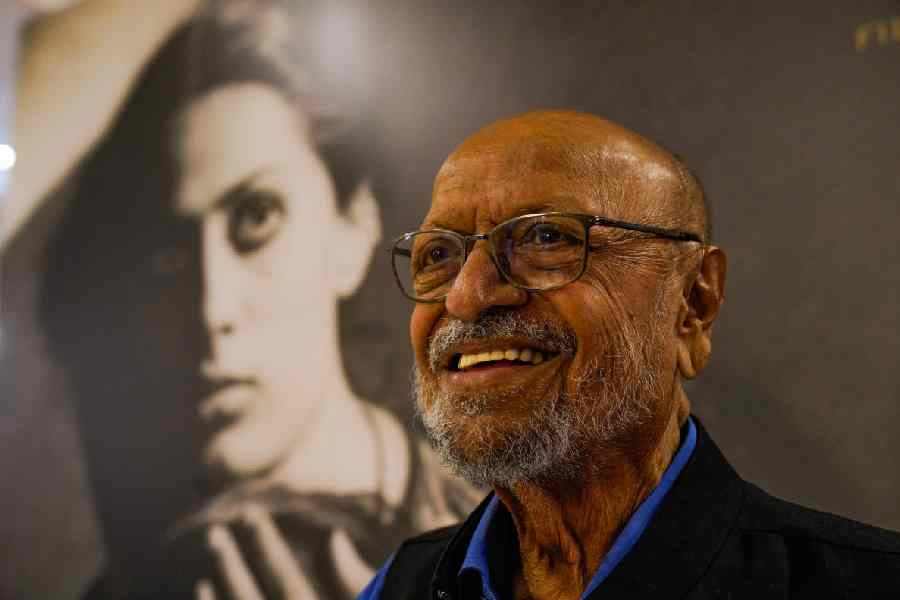

Author name: By Mihir Vatsa,

Publisher, price: Speaking Tiger, Rs 450

Mihir Vatsa’s exploration of his home turf, Hazaribagh and stretches of Chhotanagpur, is layered, fusing two journeys into one. There is the sojourn that is literal: Vatsa, battling depression and homesickness, returns to Hazaribagh in search of healing after a stint in Delhi. The other, metaphorical — hence less obvious — path that he follows simultaneously leads within. The choice for the reader is to pick up the scent of both trails.

The pleasures of the physical journey are numerous. It lays bare, unhurriedly, the contours — real and imagined — of not just Hazaribagh but, more importantly, of Meru, Daru, Banadag, Murki, Barhamoriya — obscure dots that constitute Hazaribagh’s hinterland. What enriches the reader, hitching an imaginary ride along with Vatsa in his Alto, is the entire arc comprising characters, history, politics, environmental concerns and even literature that the journey covers — or uncovers. Fused — seamlessly — by a shared enchantment of or connections to Hazaribagh are Captain Robert Smith — he ‘founded’ Tiger Hill — John Houlton and S.P. Shahi — they made Canary’s beauty “accessible” — John Martin Coates, the landscaper of the famous lakes whose origins, Vatsa notes, lay in indigenous, penal labour. Equally engaging are the archival-literary gems that Vatsa digs up, ranging from P.C. Roy Choudhury’s Hazaribagh Old Records to Tagore’s memoir of a trip.

The wandering is enlivened by Vatsa’s prose. Combining finesse with philosophy and political awareness, the narrative, more often than not, is usually as agreeable as Hazaribagh’s air: “[A] hill may be a cultural entity, but that culture is grounded in class. There is a difference between those who come to see [Canary] hill for a few hours and those who... can afford to... live by it.”

The journeys intersect in the Epilogue in which Vatsa informs of his return to Delhi, thereby suggesting that home, Hazaribagh, is more than a refuge: it is also an armour that one carries — wears — for the journeys that lie ahead.