As people milled about and ate and drank (Blue Lagoon only, but still) and gushed over the young couple who were now sparkling on the makeshift stage in the naach ghar, Boro Jethu found himself stranded in a corner of the glittering courtyard, listening to AJ’s 93-year-old great-grandfather talk and talk, even as he unobtrusively used his tongue to tease out bits of cauliflower (from the shingaras) that had got stuck between his teeth. Should have been mutton, Boro Jethu sighed. Meanwhile, the chief reason for the vegetarian menu, the great-grandfather himself, hard of hearing and consequently given to monologues, was talking loudly about classical music — or wait, was it demonetisation?

As Boro Jethu wondered how to get a sentence in edgewise — “Please come this way for dinner, it is time,” — he spotted Aarjoe Choudhury walk past. It couldn’t be Aarjoe though, could it? Why on earth, what for? If there were any doubts about the face, years had passed and Boro Jethu’s memory for names and faces was no longer what it was, the fine suit made of exquisite wool and the over-polished Oxfords belied his doubts. It was indeed Aarjoe Choudhury, looking as dapper as ever — he had been surprised when Munni fell for that peacock — even though his hair now bore prominent silver streaks.

Boro Jethu frowned.

Who had invited Aarjoe?

Surely not Munni or Manjulika. However modern they might pretend to be, he was certain that neither of them would have gone that far.

Boro Jethu was also seized with a different concern now. What was the protocol for such a situation? An ex-jamai turning up — uninvited by most counts — at a family wedding? Ex-family, that is. Surely the Ghoshes were as ex to Aarjoe as he was to them?

Boro Jethu looked about himself, discomfited. Would we ask him to stay on for dinner? (Well, the dinner itself was a kind of punishment, come to think of it, so yes, we should.) Where was his wife when he needed her? Gadding about with someone, right next to the happy couple, no doubt, so that every photograph included her in that loud turquoise Kanjeevaram she should have stopped wearing two decades ago.

Boro Jethu grabbed a panjabi-clad shoulder from the vicinity — it turned out to be a nephew — and bossily introduced him to the Jaiswal patriarch. The monologue continued after that small interruption and Boro Jethu was able to excuse himself. Where was that Aarjoe?

What a grand wedding they had thrown Munni. The oldest daughter of their family, “Roopey Lakshmi, guney Saraswati” people had started saying after she went to IIM, fatherless on top of that. Doing right by her had been vital to the family’s character. (“I didn’t know we had any,” his irreverent son Goopy had chuckled.) The ceremony had been flawless, executed by the uncles. Of course, that Manjulika had interfered in every decision — what flowers, what colour lights, what kind of fish fry.

Boro Jethu tried to negotiate the crowds as he tried to pick out the charcoal grey suit from the palette of colours that the evening had now devolved into — the pastel-pink sherwanis, the beige tussores, the midnight-blue Balucharis — and, inexplicably, as the waiters flashed past in white and the crimson anarkalis of the groom’s sisters twirled at his nose, Boro Jethu felt a kind of exhaustion surround him. He wished Goopy were here. He wished he could have sent Goopy to deal with the ex-jamai protocol. Instead of having to tell everyone loudly that Goopy was now being tenured at a fancy New England college, that Goopy was writing a novel, that Goopy was doing wonderfully, he wished Goopy were here today so they could have had some robust disagreements.

Boro Jethu stopped to catch his breath.

It suddenly felt so difficult, the act of filling his lungs with air and letting it all out, that most primal of all human impulses. He stalled. The house was practically falling apart, all manner of real estate crooks were circling above it like vultures, none of the young people were remotely interested in staying, the whole city was becoming a giant briddhashram. Boro Jethu clutched onto the pillar.

“Borda, are you okay?” Manjulika gently tapped his shoulder, “Should I get you a glass of water?”

Sudhiranjan Ghosh came to. He looked at his sister-in-law and smiled wanly.

“Look at them,” he said.

Manjulika followed his eyes.

“Is that Aarjoe? What on earth is he doing here?”

Framed through the Etruscan pillars that surrounded the courtyard, with their fierce lion faces, Lata Ghosh and Aarjoe Choudhury, deep in conversation, looked as handsome as they always had.

“If things had gone the way they should have, they would have had two teenaged children by now,” Boro Jethu sighed.

“But they would have still been unhappy, Dada,” Manjulika said softly, “Come now, eat some kochuris before the oil becomes old.”

Boro Jethu allowed himself to be led away. “We Ghoshes have always followed protocol,” he said, his voice thick. “Even if he’s come uninvited, we can’t let him go hungry. Even if he’s ex, he is a jamai after all.”

***

“I heard a little rumour that you might come,” Lata Ghosh told her former husband, the one she had agreed to marry on their fifth date and whose looks had so perfectly complemented hers that even Ronny had told Aaduri, cryptically, after he’d met Aarjoe a few months after Lata met him, that they were indeed the lead pair. “But I didn’t really think you’d come. For one, you keep complaining about Calcutta on Facebook. For another, it’s a bit too cool, no, even for you, to saunter into the wedding of an ex-sister-in-law, when none of the elders have invited you?”

But Lata said this, smiling, and Aarjoe Choudhury felt that familiar heat about his neck. The one thing that had remained unchanged through all the years of rancour, the sudden warmth that came from his memory of their very first meeting, when Lata had come in for the interview and he’d been instantly swept away. (Of course, the single memory, while visceral, had never been enough for the rest of their life.)

“I was actually in Calcutta to wind up the old house. Now that Ma and Baba are gone, there’s no reason to keep the flat. And...”

“I am so sorry,” Lata said.

(Aarjoe’s mother, it must be noted, had been a Class A bitch. But his father had been a gentleman.)

“Since you were in town, almost serendipitously, I thought we should meet. There were a few important things to discuss, though now’s not the time for that. Shall we go meet Molly?”

Aarjoe slipped out a little Tiffany box from his pocket.

“Ever the show-off,” Lata remarked raising her eyebrows. She led the way to the naach ghar, “I was sorry to hear about you and Maria.”

“Oh well,” Aarjoe said, changing the subject, “Do you remember the house we nearly bought in Connecticut?”

“Of course,” Lata says, “I sometimes wonder if the ‘three-car garage’ was real or something I imagined afterwards. Now that I live in London, we are quite embarrassed about cars and garages.”

“My colleague — you remember Nick? — well, Nick had bought that house eventually. And every time I visit, I think of the life you and I could have had there.”

Lata maintains a studied silence.

“Nick has three children, all brats of course. But we’d have sent ours to a public school, right? So they wouldn’t have been brats...”

Lata stopped in her tracks.

“Why are you here, Aarjoe?” she asked, now facing him squarely.

***

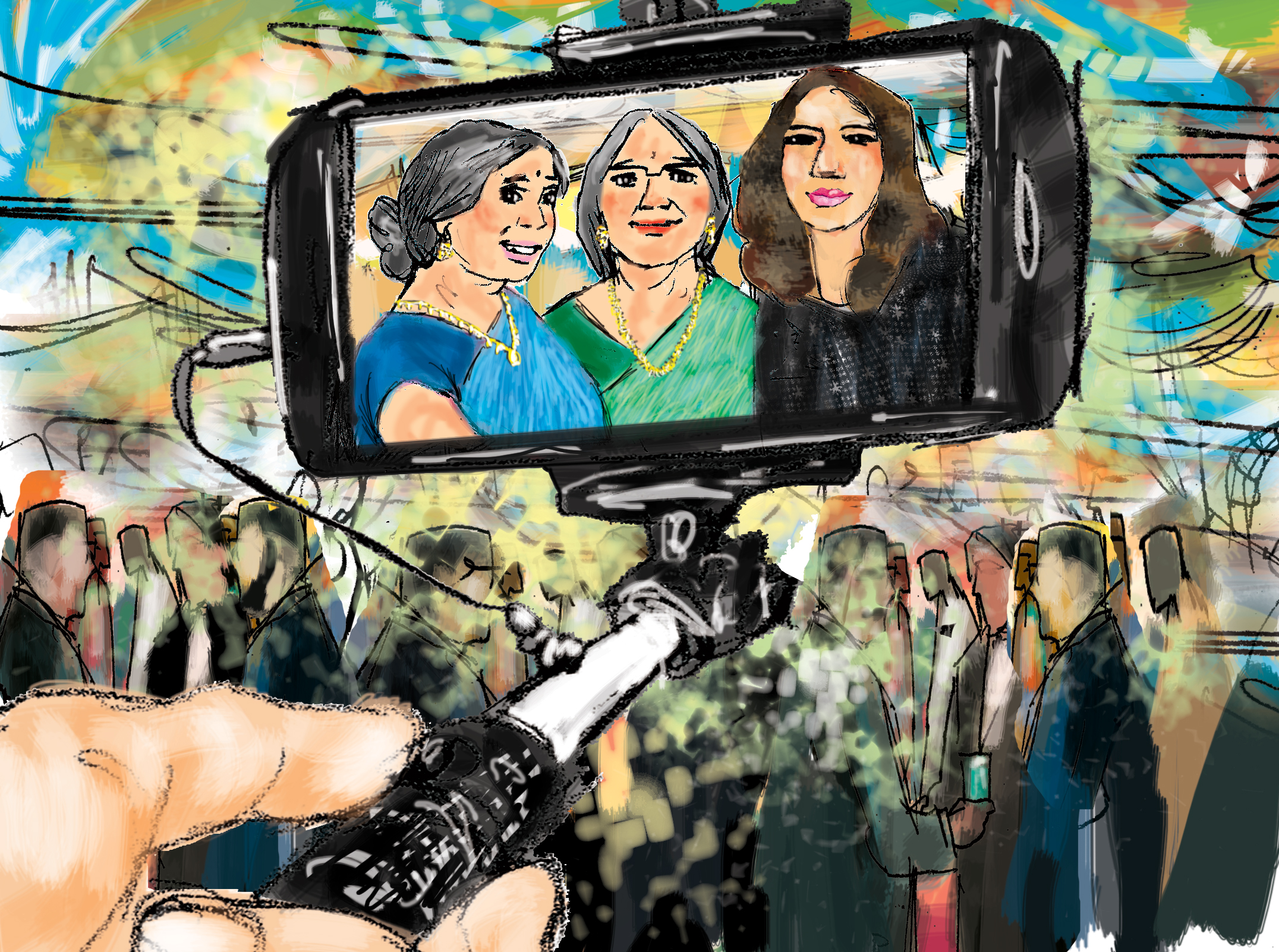

Bobby Bansal, the other liaison officer of the Ghosh-Jaiswal wedding, had one eye on her phone and the other on Lata Ghosh and the handsome interloper when her mother and aunt — in matching chiffon saris — walked up to her, armed with a selfie stick.

“C’mon now, stop looking at your phone and give us a smile,” her aunt said.

Bobby obliged, pouting at her aunt’s phone in the manner she’d seen Pragya and Mimi do.

“I didn’t know your Ronnyda was so close to the Ghoshes,” her mother said, sipping her drink.

“Hain na?” her aunt, the groom’s mother, chimed in. “The Boro Jethi told us abhi abhi. Nice lady. So friendly, not like the husband. It seems your Ronnyda and this London Lata had a big love story. Everybody thought they’d marry.”

Bobby looked surprised for a moment and then her face became neutral again.

(To be continued)