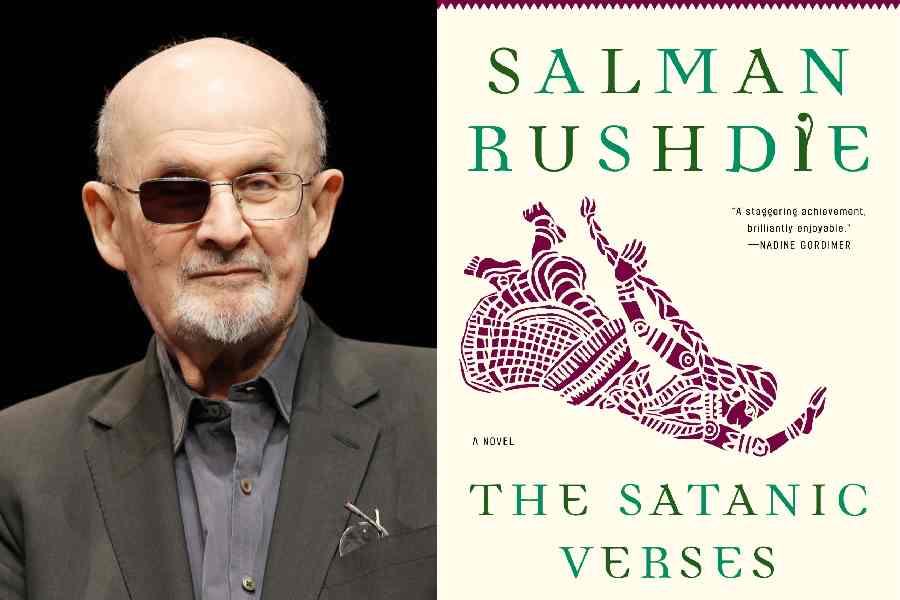

Book: The Last Heroes: Foot Soldiers Of Indian Freedom

Author: P. Sainath

Publisher: Viking

Price: ₹499

The Last Heroes has a small — telling — note by Professor Jagmohan, the nephew of Bhagat Singh. The passage includes the following conversation between Bhagat Singh and a compatriot: “We, as soldiers of freedom, love action, and in the action the most honoured are those who either achieve martyrdom in the field or at the gallows. But they are nothing but the gems on the top of a building. They only enhance the beauty of the building. But the stones which make the foundation are much more important. They strengthen the foundation and provide long life to the building. It is they who carry the burden for many long years.”

P. Sainath’s book concerns, in essence, these proverbial ‘stones’ — men, women and children who participated in the freedom struggle, the foot soldiers whom the nation has forgotten. Several factors compelled Sainath to confront this national amnesia. “The youngest of those featured in this book is 92, the oldest 104”; thus, “[i]n the next five or six years, there will not be a single person alive who fought for this country’s freedom.” The author’s grandfather’s role in the freedom struggle — unveiled in a delightful anecdote — may have planted the original seed of curiosity for the forgotten ones. More revealing and instructive are the restrictive conditions imposed by successive myopic bureaucracies for inclusion in the lists of freedom fighters that, Sainath shows, remained unrepresentative. For instance, “[o]nly those earning less than Rs 5,000 a year were eligible” to draw pension from the first such scheme for freedom fighters in 1972. The Swatantrata Sainik Samman scheme eight years later may have been generous but still demanded an eligibility criterion of “minimum imprisonment of six months in mainland jails before Independence”.

Laxmi Panda’s stinging rebuke — “Because I never went to jail, because I trained with a rifle but never fired a bullet… does that mean I am not a freedom fighter?” — that Sainath quotes exposes the fallacies in India’s official remembrance project.

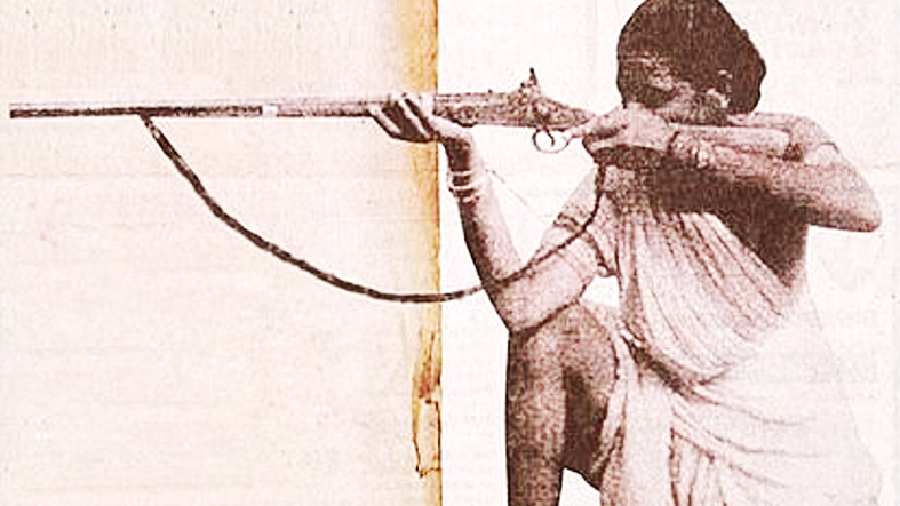

But thanks to Sainath’s research and travels, the nation has now been nudged — jolted — into remembering many of Laxmi’s fiery peers. Among them are Hausabai Patil who, as a member of the Toofan Sena, participated in some daring raids on British trains and police armouries; Demati Dei Sabar, all of 16, had charged at the British police tasked to quash the Saliha Uprising; Shobharam Gehervar escorted Chandrasekhar Azad to a secret bomb-making unit; Mallu Swarajyam (picture) had taken the battle to Telengana’s feudal tyranny; Thelu and Lokkhi Mahato of Purulia occupied an interesting intersection between Bapu and bandits, and several others.

The chronicle of azaadi has always been a political project. The ruling regime’s eagerness to correct ‘imbalances’ in the official historiography bears proof of this. But Sainath’s book is a double mnemonic tool: it forces Indians to remember the twilit realm of patriots and revolutionaries on the margins of the national consciousness while reminding them that reclaiming — democratising — the narrative of freedom is a public responsibility.