Book: Young Mungo

Author: Douglas Stuart

Publisher: Picador

Price: £9

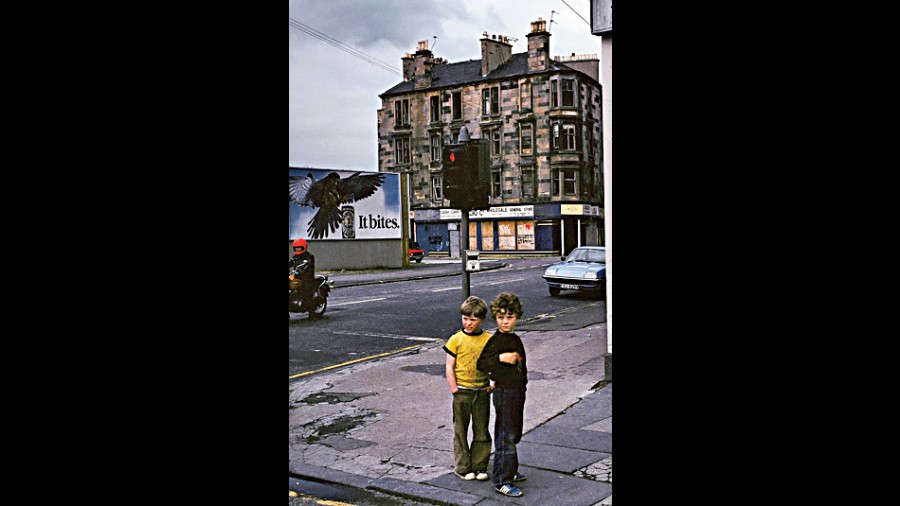

Coming of age is a ritual often practised in many cultures. Tearing the child away to make a man out of him is the opening act in Young Mungo, which is a contrast to the novel where the protagonist has to deal and come to terms with his sexuality in Glasgow in 1989. The plot opens with a scene where Mungo is being led away from his tenement home as his mother, drinking a tea mug of fortified wine, watches impassively from a window. He’s — reluctantly — in the company of two men who take him off for a camping trip where he is to be taught to gut fish, make a fire, and learn to be a man.

Mungo in the beginning is a child-man — “nearly a man” — and is dealing with the strong pull of the umbilical cord, be it with his “alkahawlick” Mo-Maw, the “Haaah-ha-ha”-ing Jodie Hamilton or the kind Mrs Campbell. The novel is an oscillating pendulum between a sinister, foreboding present and a past which is also similarly murky. Douglas Stuart weaves in characters who are “rare sort of handsome”. The characters’ mundaneness makes them endearing despite being flawed.

The sunshine in Stuart’s narrative is the odd romance that blossoms between James, a Catholic boy, and Mungo, the Protestant. Unlike the strong overbearing male figures, James is gentle. The gentleness is very beautifully portrayed through his obsession with doves. The lacing together of pinky fingers in the dark recluse of a bedroom soon grows into a love that challenges two of the most powerful taboos: the concept of heterosexual masculinity and Protestant-Catholic intermingling.

“Masculine pursuits” of the toxic industrial world of Glasgow is the running narrative of the novel. The expectation is always to follow the route that will “make a man out of ye”. Switchblades, street-fights, boy gangs dominated by his elder brother, Hamish, make up for the absence of a father figure in Mungo’s world. However, the undercurrent of the love story is the reality which makes the novel a classic. It is like a cross between the worlds of Stephen Dedalus and Oliver Twist. Apart from Mungo and James, Jodie captures the reader’s imagination and sympathy. Her lost childhood makes one ache for her and, yet, Stuart leaves no space for sentimentality.

The novel straddles comfortably between a thriller and the sensitive exploration of an adolescent boy. The only drawback is Stuart’s zeal to overexplain every situation. It is as if the reader cannot be trusted to draw the right conclusion — “There were tears on Jodie’s face for Mrs Campbell, but it was easy to pretend she was worried about a burnt steak and kidney pie.”

However, despite the excesses,Young Mungo ends with a sigh. A sigh that is filled with both hope and sadness making it a piece of poetry in prose.