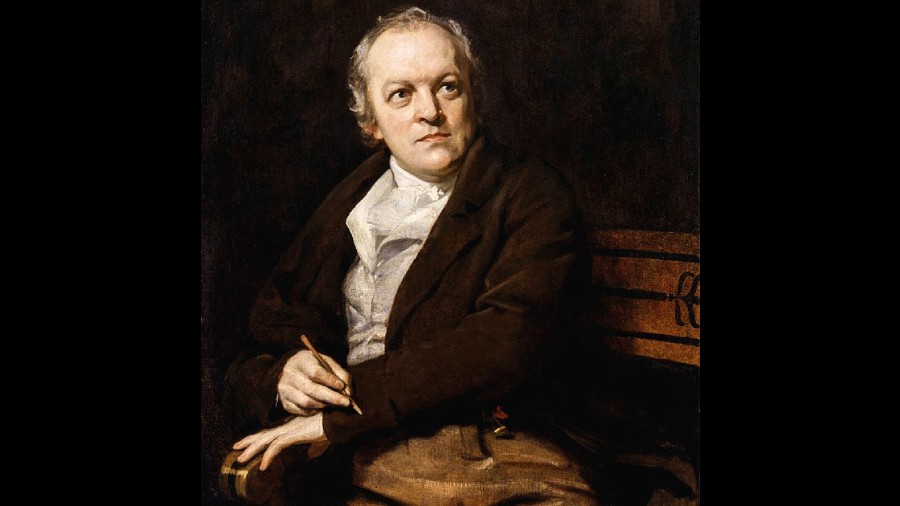

Book: William Blake VS The World

Author: John Higgs

Publisher: Weidenfeld and Nicolson

Price: £20

During his decade-long career as a professional writer, John Higgs has managed to shed light upon various issues that permeate modern social and cultural thought. William Blake Vs the World is his second work on the visionary poet and artist who was largely misunderstood in his own time. After having spent a life in almost continuous poverty, William Blake was unceremoniously dumped in an unmarked grave at the Bunhill Fields dissenters’ burial ground — a name derived from “bone hill” as the site had become a popular disposal ground for the unwanted dead.

Higgs begins very aptly with an account from the diary of Henry Crabb Robinson, a man who was a dear friend of Blake’s, that read, “Shall I call him Artist or Genius — or Mystic — or Madman?” It was indeed a struggle for most of Blake’s acquaintances to formulate concrete opinions about him. As Higgs recalls from several reports about the poet’s life, including Alexander Gilchrist’s biography of Blake, he was often seen, especially in later middle age, as angry, rigid and egotistical. Higgs, however, is quick to clarify that these opinions were mostly formed by those over whom the enigma of Blake’s personality loomed like Urizen grown “into a dragon form — angry, cruel and cut off from the light beyond”.

Higgs sets out to correct these misrepresentations of Blake’s character and, in the process, ends up analysing the four qualities that Robinson had attributed to the poet. While endeavouring to reach the depths of Blake’s complex but complete mythical world and system of “celestial” beings, Higgs draws upon a variety of starkly diverse fields of study, in all of which he finds delicate traces of the Blakean philosophy. Starting with the theories of psychologists like William James and Carl Jung to explain Blake’s “two-fold vision”, Higgs travels into further scientific intricacies sparked by neuroscientists like Robin Carhart-Harris with their studies of “entropy” of the brain. He doesn’t stop there but moves into the physics of Einstein’s relativity and finds his way into the science and the mysticism of Emanuel Swedenborg, a name well-known to Blake and an individual our visionary poet came to hold in contempt. In Blake’s theory of the universe, the real and the imagined are the same in so much as they flow from the mind of the individual himself. In such a universe, god himself becomes a creation of man, thereby establishing that the world we perceive is relative to our own being.

Higgs also expertly manages to contextualise Blake’s growing distress as well as the deepening complexities in his philosophy in his sustained poverty and the adamant refusal of the world around him to recognise his brilliance. In a world with dangerously shifting paradigms in the continued movements of the Reformation, the French and American Revolutions as well as the rapid industrialisation of Britain, the Blakean philosophy could certainly have lent some perspective. As Higgs concludes, it was only in the very last years of his life when Blake was, in his own words, “very weak and an old man feeble and tottering”, did the poet find the respect and the awe he deserved, first in the admiring group of young artists calling themselves Ancients that flocked around him and, then, in his firm inclusion into the group of poets writing in his time: the Romantics.

Higgs manages to neatly place what was thought to be the frenzy of a madman into the realms of modern science and comparative religion. Blake’s zeal resonates with Taoism as much as it does with Norse and Welsh theologies. Through Higgs’s eyes, we see Blake emerge as the prophet, triumphant versus the World. It is safe for us to conclude that he was indeed, Artist, Genius and Mystic, albeit a little mad! The painter, George Richmond, then a young man of eighteen, was the one who closed Blake’s eyes when the poet died, “to keep the vision in”.