Perumal Murugan, the sublime writer of fiction in Tamil and the creator of award-winning works like Poonachi (translated by N. Kalyan Raman) and Madhurobhagan (One Part Woman; translated by Aniruddhan Vasudevan) decided to explore what are famously considered errors in fiction-writing while penning his latest offering, Estuary (Eka; 243 pp; Rs 499). “One could call it deviant to be excited by errors. Deviance has been the starting point for various arts,” writes the author in the foreword of the tale set in Asuralokam, where a father and a son navigate a world that is oftentimes sinful. Kumarasurar spirals down a path of extreme anxiety and distress upon hearing a seemingly innocent request from his son who is away in college. Set in an urban setting, the tale is a commentary on our social surroundings through the musings of a father. It doesn’t take a reader too long to understand that we reside in Asuralokam ourselves and find bits of ourselves in Kumarasurar’s troubles and his son Meghas’s demands. Translated into English by Nandini Krishnan, who has also previously written books in English called Hitched: The Modern Indian Woman and Arranged Marriage and Invisible Men: Inside India’s Transmasculine Networks, Estuary is a free-flowing ride down a stream of consciousness that few authors can successfully achieve. The Telegraph spoke to the author and his translator over email to understand the thoughts that went into penning Estuary. Excerpts.

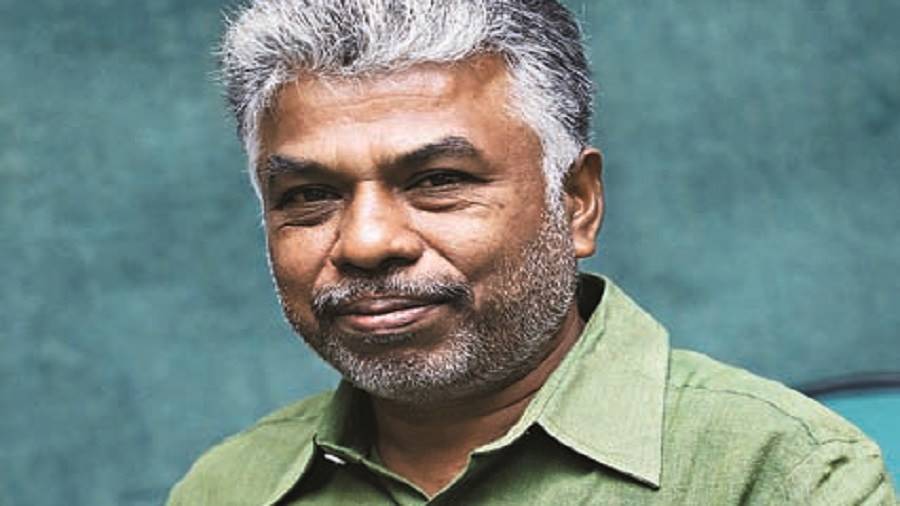

Perumal Murugan

What made you suddenly depart from a rural setting and set Estuary in an urban setting?

So many unexpected things occur in one’s life, and so they do in one’s writing. You could plan for every circumstance, but then something entirely unplanned might happen all of a sudden. This novel, with its urban setting, is one of those things that just came to me. Initially, I had my doubts about whether I could build an entire novel around this new backdrop, but as I wrote, the story grew. It became hard to control my fingers as they typed away.

Tell us about the Estuary journey, from inception to execution.

As with rishis and rivers, it’s hard to trace a novel to its origin too. There is no one in my generation who doesn’t complain about their problems with their children. One seems to be able to talk only about one’s offspring. I’m a writer. I’m able to view things from various perspectives. And so I tend to point out how the situation must appear from their children’s perspectives. It must have been such conversations with my friends that became the seed for this novel. Once I decide to write a novel, I first write it in my head. And so I did with this one. When I needed some information, my son helped me out. I wrote the bulk of it during a month-long writer’s residency at Manipal University. I finished it a while after returning home.

You have said in your foreword that you purposely wanted to fill your book with ‘errors’. Could you tell us about the thought that led up to it?

It has been a long-time desire of mine to try using the aspects of writing that are deemed flaws — by accepted grammatical and structural norms — as tools to create literature. I explored some of these techniques in this novel. It occurred to me that they would suit its style. Literature is something that transcends norm and form, isn’t it?

Do you feel that there is a change in the censorship mindset in India for better or worse? How does one find the strength to continue to tell relevant stories?

The censorship mindset in India is only getting more stringent. The arenas in which man’s life play out are expanding, and yet our perspectives are growing narrower. The reason for this is that, from the lowest to the highest positions of command, everyone wants to exert one’s authority. Will we ever see a time when people understand that peace can only last without authoritarianism?

How important are awards and nominations to you?

They are not important. There is no need for a writer to think about awards.

What is your writing process like?

I need complete isolation when I’m writing. Words, food and sleep are my only voluntary indulgences at this time. I listen to a bit of music. I need coffee often. That’s about all.

Did you have an ideal reader in mind when you wrote Estuary? Because of a dearth of descriptors, it is easy to imagine yourself as an asura in certain actions of the characters in the book. Was that the purpose?

I don’t think about readers at all when I’m writing. It is only after I finish the first draft that I sit back and wonder what readers will make of it. While revising my subsequent drafts, I do a few things keeping the reader in mind.

It remains for me to expand the world of asuras in my future writing. I plan to save my descriptors for those books. As far as this novel was concerned, I felt names were about enough.

Have English translations of your book affected your writing journey beyond the broadening of an audience base?

My novels were written without any thought of an English readership. It was some years after they were published in Tamil that they were translated into English and other languages. Now, Poonachi and Estuary have been translated almost immediately after release. My experience has been that as long as I create a novel to my satisfaction in my language, it will hold its own in any language. And so I don’t write with the prospect of translation in mind at all. It does give me great joy that my readership has expanded thanks to translation.

Nandini Krishnan Sourced by the Telegraph

Nandini Krishnan

What drew you towards translations and Murugan?

I guess it is my love of languages that drew me towards translation. Several of my favourite writers including Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Milan Kundera, Jorge Luis Borges, Tahar Ben Jelloun, Banaphool, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Orhan Pamuk and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn were initially accessible to me only through translation, and I think it is a very crucial and sadly neglected aspect of world literature. My first stint with translation from Tamil was when I wrote a profile of the poet Salma for Fountain Ink magazine. I felt the existing translations of her work didn’t do the original justice and asked permission to translate excerpts myself to go with the profile. Her publisher Kannan Sundaram is also Professor Murugan’s publisher, and he asked me if I’d like to translate him.

Do you feel the landscape of literature in regional languages is changing?

We won’t know much about non-English Indian literature unless translations are commissioned regularly. We have the impression that “regional literature” is playing catch-up with writing in English. But there have been searing works across languages. I often say we’ll never know how many Vikram Seths or V.S. Naipauls exist in other languages unless publishers decide to invest in careful translations. Has anything like Aranyak or Sila Nerangalil Sila Manithargal been written in English?

Since this was your first translation, how was the experience?

It’s interesting how someone else’s characters can become one’s own when their thoughts are metamorphosed into another language. I felt myself becoming protective of the characters, the story, and the author himself. Reading the novel so many times, both in the original and while reworking my drafts, I saw just how layered it was, and it made me think about how much we miss on a first read.

What were the most difficult as well as the best parts of the translation process of Estuary?

I think the best part was discovering just how beautifully Perumal Murugan, who is one of my favourite writers, has evolved after he has placed certain restrictions on himself. He hasn’t tackled social issues head-on in this novel, but worked them into its fabric — just as they are constant motifs in the fabric of our lives. In that sense, it is his most mature novel. And the responsibility of translating something so precious was huge. The translator in me was under a lot of pressure from the reader and critic in me.

What can we expect next from your table?

I’ve been working on a novel in which I’ve tried to mix various media — graphic novel, music, playwriting, poetry and narrative. I hope that will see the light of the day next.