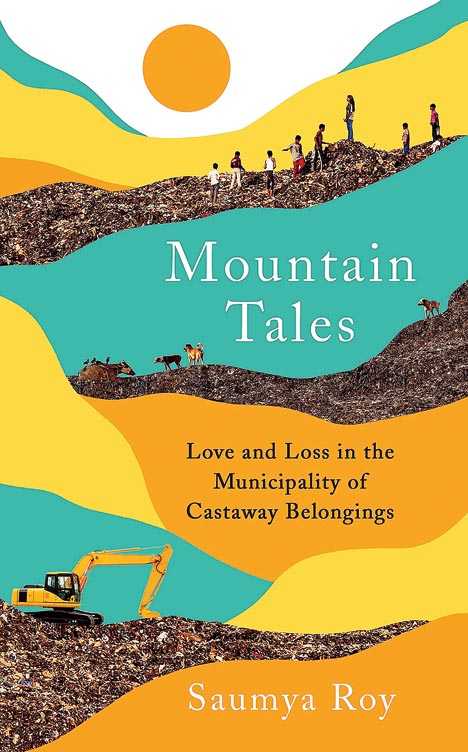

A former journalist, Saumya Roy quit the profession in 2010 and continued writing about financial inclusion. She soon began a non-profit, which involved meeting all kinds of people. Micro-finance was the chief project that her company dealt with and it was through that initiative that she met the waste pickers of Shivaji Nagar. The former journalist was fascinated by their lives and started frequenting their doorsteps to learn more. What emerged from the intense research spanning years is the book Mountain Tales: Love and Loss in the Municipality of Castaway Belongings (Profile Books; Rs 699) revolving around the Deonar municipality of Mumbai.

Made up of the waste-picking community, here is a tale of love, loss and human existence in its rawest form in the heart of the city of blinding lights. That non-fiction could be as moving is a fact that takes you by surprise. As Deonar’s toxic wasteland holds together the lives of these people who have bared it all to Roy to have their stories heard, there is an undeniable theme of solidarity emerging from the pages of this seminal work that is deeply rooted in research. We spoke to the author about her driving forces and the incredible world behind Mountain Tales. Excerpts….

Could you tell us a little about your work at the small finance bank which sort of led you to the place that you write about extensively.

One of the areas that my non-profit worked on was microfinance, along with a bunch of related livelihood initiatives. We started getting these waste pickers coming to our office and from the very first look, one could tell that they were different. Even their physical appearance was striking because they had cuts and bruises from the work they were doing. They were earning and this was one source of income that would never run out –– it was waste. I had asked someone how she was going to use the money and if my loan stood to go bad. What she replied can be found in the first few pages of my book. She said: “Is waste ever going to reduce? We are never going to be out of work and we can endlessly grow our business.” I was immediately fascinated. I started going there religiously. It was a fire in 2016 that compelled me to start penning my experience. I began reporting quite obsessively till it became a project.

What do they do with the loan that you give them? How is it that they grow their business?

In 2016 when I began writing about them, I had to taper off the lending business to avoid conflict of interest. I didn’t want anybody to speak to me because I was lending them money. They should speak only because they want to speak, want their stories to be heard and not for any other reason. Most chose to speak to me for which I am grateful. Someone wanted to set up a zari or embroidery business, some wanted to sell shoes while some would rent out rooms and be a kind of real estate broker and everyone had plans with the money they received, which involved getting out of waste picking. You’ll often find that the poor do lots of different things to get by.

In some ways, your book is also a cast commentary. What are your thoughts on that?

It is about cast and it’s about religion. It’s a deeply human story. But I think it’s not a coincidence that waste-picking communities in India belong almost exclusively to a particular cast. I wouldn’t use the word lower castes, because obviously there’s a connotation to it. The area I speak of, Shivaji Nagar, had a mixed community till the 1992 riots. After that, anybody with a little social mobility left and the ones who were left behind were mostly Muslims. So in a way it is a comment on the social mobility in our country. Christophe Jaffrelot has a new book and his research clearly shows over the last 20 to 30 years, a connection between religion and caste and the detritus of our society, the lower rungs of our society. And it’s not a coincidence that there are certain people doing these jobs. I’ve had people ask me, ‘why don’t these people leave?’ I feel like asking them, ‘Where would they go?’ These are not people who can just get a call centre job or a job in the gig economy.

What is the education system like in these areas?

Actually, this is the ward with the highest number of municipal schools and the highest rate of dropouts. I visited schools and classrooms, met teachers, principals in this area. There’s a lot of background research that’s gone into it that didn’t even make it to the book. But I definitely spent time in schools and clinics around there. There’s a combination of reasons why the education system fails them, partly because poverty is so deep that even at the age of 10 and 11 they do feel the need to make money every day. So while they are enrolled at school, the draw of that garbage mountain is tremendous. Children start working at the tender age of five or six. There are addictions too that keep them working because they are obviously undernourished. Where else will they get money to buy cigarettes or glue? You get that by working as a waste picker and not by going to school. It’s both the system failing them and poverty dragging them back.

What kind of research did you have to do? And what was your research process?

My entry point was obviously through my conversations with them, learning about their lives as waste pickers. Having said that, I became very drawn to the document-based research. I found out about train lines in this area that would bring garbage. This is true for Calcutta as well I believe where trams would arrive at the Dhapa bearing waste during the colonial times. My research extended to Calcutta as well though it isn’t a part of my book. I initially couldn’t believe this could be true but I checked up at an Oxford University library and found her to be absolutely right. There indeed was a train line that was made during the plague.

They also told me there is a court case going on regarding the area but that doesn’t seem to impact their daily lives at all. In 2017 there was a court order passed that said no construction work that added space to the city would be allowed. I attended 300 hours of court hearings to see if this would impact their lives. It seemed when I went to court that something would happen. The urgency in the air, the setting of deadlines, the threats. But then I realised that this court case has been going on since 1996! Lots of very reputable and distinguished judges have presided over it, including Justice Chandrachur. So you feel like something is going to happen but nothing eventually does. The place is exactly the same, the same issues for 26 years! And I also realised that while this was about garbage that is limited by scope of space, the same problems could be transposed to noise pollution or multiple other issues plaguing our country as well as others.

What is your dream about this book eventually achieving?

To move readers. You know how when you read fiction, you get immersed in the world. You feel moved. You feel like you are in this world and you do not want to come up for air. As a reader, you tend to love that experience. So I just want people to be similarly moved by this non-fiction book, by the experience of this world.

And then yes, when they come out, as with any book, you feel you’re a little bit transformed. That for me would be ideal.