The book under review is the South Asian edition of J. Barton Scott’s Spiritual Despots: Modern Hinduism and the Genealogies of Self-Rule. Scott’s is a scholarly exposition of the lineages of the “self” that emerged in South Asia since the 19th century within the rubric of Hinduism. It will be pertinent to note, though, that the genealogies of what we now understand as “Hinduism” require the critical (re)appraisal of an array of historical forces. On the one hand, the bulk of post-colonial literature would ascribe to the colonial order the credit of “inventing” a structured religion called “Hinduism” that marked the coalescence of the diverse overlapping devotional cultures spread across the subcontinent.

On the other hand, more recent scholarship has perhaps more meaningfully traced the genealogy to pre-colonial cultural processes and formations, drawing attention to the internal dynamics of the diverse socio-intellectual strands that would eventually lead to the modern entity of ‘Hinduism’. Each of these perspectives, and their variants, are of course susceptible to (mis)appropriations. Scott, however, cautiously recognizes the relevance of the longue durée narrative of the latter position while simultaneously highlighting the key role the priestly community played in reifying certain ‘Hindu traditions’ during the colonial period. Scott explores how the authority of the priestly community in this process subsequently came to be disparaged by both the English missionaries as well as sections of Indian intellectuals within reformist circles that led to multiple contesting approaches to the “self”. Scott’s engagement with, and interrogation of, the idea of the “self” then involves in large measure a critique of brahminical hierarchy and “priestcraft”.

This book tells the story of this dawning critique among sections of South Asia’s thinkers in the western parts of the subcontinent. Through six well-researched chapters, Scott explores the complexities of this process against the larger backdrop of the Protestant critique of the Catholic order, the different shades of liberalism and their fate in colonial India, and the resultant narratives of reformism that animated the socio-religious and intellectual life of colonial India. This then is also a history of cross-cultural flows between the European and South Asian worlds.

Scott’s story leaves its own trademark in significant ways. For one, this is no simple linear story of a derivative Hindu narrative of anticlerical invectives and resultant reformism. Scott acknowledges the relevance of the scholarship inter alia of Max Weber, Michel Foucault and Charles Taylor, but builds upon and takes forward key aspects of some of their core arguments. The “worldly ascetic” in Scott’s narrative is thus not merely an empowered individual turning towards ‘this-worldly’ activism, but someone who does so through self-discipline, at times conforming to recast idioms of obedience, and with a keen awareness of the principle of “elective affinity”.

Affinities, for Scott, do not mean connections forged through linear family relations; they refer to connections akin to Goethe’s relations of spirit and soul (Geistes- und Seelenverwandte). Thus Keshub Chunder Sen is credited for having developed a vocabulary of “spiritual affinity”. By contrast, M.K. Gandhi is said to have replaced the “liberal individual” or the “self-interested citizen-subject” or the “sovereign citizen” with the “self-negating man”. Gandhian secularisation, in Scott’s formulation, ought not to be understood merely in terms of an “exit from priestcraft”, but a project marked by a continual journey whereby the ascetic individual through self-rule (swaraj) “facilitates a politics of horizontal connection”.

Here Scott not only conforms to the larger argument of placing the likes of Gandhi in a wider contemporaneous web of “transnational ‘ethical turn’”, but also sees Gandhi as a highly original theorist who, by way of reforming the “capitalist subject”, provided a counterpoint to Weber’s genealogy of the “capitalist selfhood”. The anticlerical polemics in 19th-century India, moreover, echoes aspects of the Foucauldian idea of the pastorate, that is, the priestly order, as a distinct species of power. In so far as religious power, in Foucauldian diction, reflected “pastoral power”, the history of secularism reflected not so much an interplay between the Church and the State, but rather that between the pastorate and governmentality. Scott reminds us here of a 19th-century narrative of secularism somewhat different from the 20th-century “Indian secularism” that came to derive its meaning in its relationship with the State, evoking idioms of majority and minority.

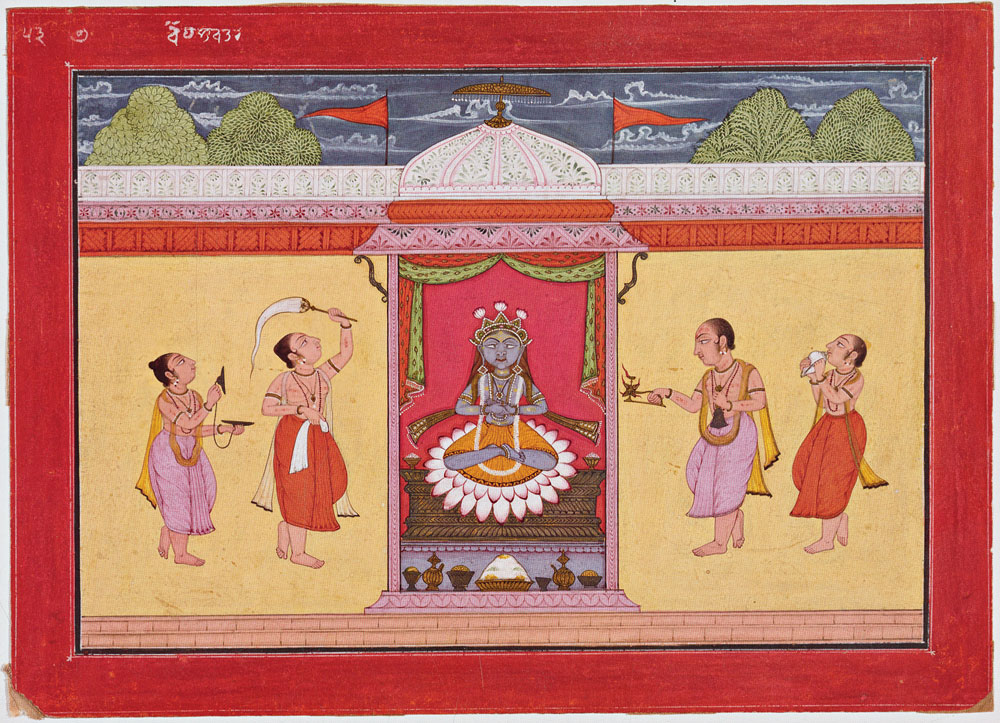

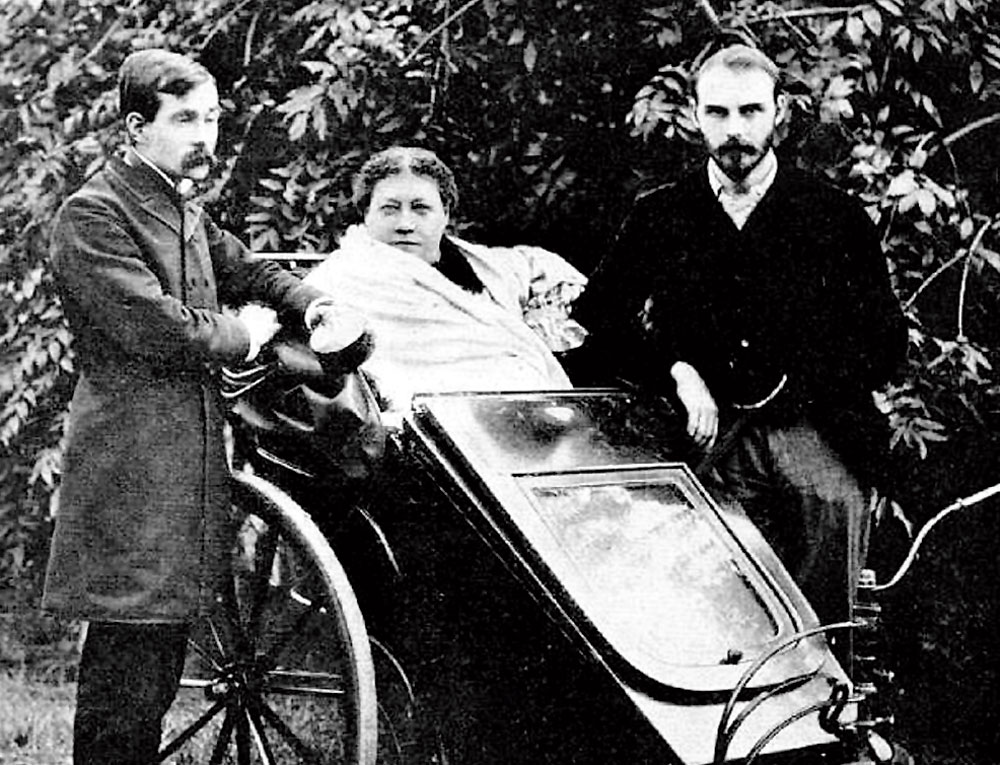

Scott’s protagonists — Keshub Sen, Karsandas Mulji, Helena Blavatsky (picture), M.K. Gandhi et al — do not necessarily conform to one single well-orchestrated narrative of “self-rule”. They do, however, share a concern for the diverse range of issues gravitating around the “self”, reworking the idea through their signature methods. The book will be of interest to those who are open to unlearn narratives of a monolithic body of these ideas and are, instead, amenable to embrace possibilities of their diachronic evolution and multiple genealogies, their ambiguities and fluctuations.

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (seated), with James Morgan Pryse and George Robert Stow Mead in London 1890 Source: Wikimedia Commons

Modern Hinduism and the Genealogies of Self-Rule By J. Barton Scott, Primus, Rs 1,195